A Pandemic Thanksgiving

Reading Time: 4 minutes.

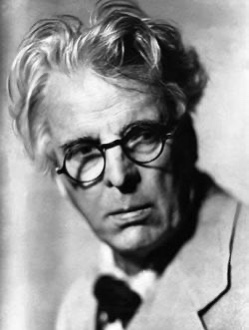

William Butler Yeats may as well have been speaking of our 2020 plague year when he famously wrote in The Second Coming that “the centre cannot hold.” Deracination, isolation, and introspection have been coupled with illness, fear of illness, unexplored economic frontiers, and a commonplace reacquaintance with exile and death that our forebears may have understood but that we find foreign. With the CDC’s warnings against holiday travel present in our mind, we may recall what French novelist Albert Camus wrote in La Peste [The Plague]:

The plague forced inactivity on them, limiting their movements to the same dull round inside the town, and throwing them, day after day, on the elusive solace of their memories.… Thus the first thing that plague brought to our town was exile.… Sometimes we toyed with our imagination, composing ourselves to wait for a ring of the bell announcing somebody’s return, or for the sound of a familiar footstep on the stairs….

Albert Camus, The Plague (1948) (trans. Stuart Gilbert) (Vintage International Edition (1991) at 71.

Unlike the music of Christmas or Easter, the music of Thanksgiving is hard to pinpoint. Shuffling leaves? The drum-brush strokes of a knife carving the turkey?

The COVID pandemic is the bewilderment plague, perhaps, and it makes Thanksgiving music—already a peculiar topic—even more difficult. Unlike the music of Christmas or Easter, the music of Thanksgiving is hard to pinpoint. Shuffling leaves? The drum-brush strokes of a knife carving the turkey? Vince Guaraldi, an early lead-up to Christmas through the Charlie Brown television-memories of readers of a certain age? An uncertain business, but here are a couple of thoughts.

First, when in doubt, start in the seventeenth century. The “Te Deum & Jubilate for Voices and Instruments made for St. Cecilia’s Day 1694” of Henry Purcell was apparently performed as a Thanksgiving piece, as noted by Michael Evans Kinney and the Stanford libraries:

While not much is known about the early St. Cecilia’s Day celebrations circa 1683, England’s premier composer, Henry Purcell (1659-1695), wrote many pieces for the festivities. In 1694, he wrote one such piece, titled Te Deum & Jubilate for Voices and Instruments made for St. Cecilia’s Day 1694. The landmark work sets an English translation of the St. Ambrose Hymn and revolutionized church music with its scoring for violins, viola, basso continuo, and two trumpets, with soloists and choir.

Purcell originally wrote the piece not for St. Cecilia’s Day, but for a Thanksgiving service to celebrate the return of King William III after a string of military successes. However, the use of instruments in the Royal Chapel was forbidden, and Purcell, not wanting to upset the Court, chose not to premiere the piece for this occasion. As a result, the St. Cecilia’s Day celebration of 1694 marked the first time that instruments were used in English church music.

The piece continued to be performed both for Thanksgiving services between 1702 and 1713 and for the Festival of the Sons of the Clergy, which took place annually at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Purcell’s Te Deum and Jubilate in D was a mainstay for this festival from 1697 (even inspiring a special print edition of the score) to 1713 when Handel’s Te Deum setting composed for the Peace of Utrecht took London by storm. From this point on, Purcell’s setting had to compete with Handel’s, which was much more fanciful.

Read the entire article here and listen to the Te Deum below, cherubs and all:

Second, let’s go to the American fountainhead—Bing Crosby with 1942’s “I’ve Got Plenty To Be Thankful For,” one of the songs on the soundtrack to Irving Berlin’s Holiday Inn (which also features, of course, “White Christmas”):

Third, to bring us into this century, here’s a Thanksgiving playlist from NPR (Shaunna Morrison Machosky): Pass the Drumsticks: Thanksgiving Jazz. And, here’s one from Spotify. I have only sampled the NPR list, but the Spotify list is solid and well-attuned to Thanksgiving: by turns swinging and reflective, it is music that does not impede your way to bar or table.

Now, what to drink?

Previously, we suggested the French 75 cocktail:

Consumed in the morning before Thanksgiving lunch, the French 75’s impression is as indelible as it is refreshing, and it is superior to a Bloody Mary. I have also noted the Gibson, which is, like Thanksgiving itself, a rite of autumn yet commercially obscure:

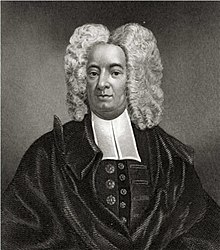

And, after two 75s or Gibsons, one might take on the famous Thanksgiving sermon of Cotton Mather (1663-1728): The wonderful works of God commemorated praises bespoke for the God of heaven in a thanksgiving sermon delivered on Decemb. 19, 1689.

Gratitude comes from the subjective heart. I cannot know yours nor you mine. But gratitude appears in the first instance by grace, then plays out in the real world as described by the 1928 Book of Common Prayer:

MOST gracious God, by whose knowledge the depths are broken up, and the clouds drop down the dew; We yield thee unfeigned thanks and praise for the return of seed-time and harvest, for the increase of the ground and the gathering in of the fruits thereof, and for all the other blessings of thy merciful providence bestowed upon this nation and people. And, we beseech thee, give us a just sense of these great mercies; such as may appear in our lives by an humble, holy, and obedient walking before thee all our days; through Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom, with thee and the Holy Ghost, be all glory and honour, world without end. Amen.

Happy Thanksgiving.