13 Books Every White-Collar Lawyer Should Read

Reading Time: 11 minutes.

Of the making of lists of books, there shall be no end. Nevertheless, herewith is one more.

Set out below are 13 works that every white-collar lawyer – defense counsel, prosecutor or judge – should read.

Why such a presumptuous project? Three good reasons.

First, lists start conversations. Although law is (or was) a “learned profession,” relatively few lawyers in my experience have read broadly or deeply since college. The press of work does not allow otherwise. Our professional learning is utilitarian, narrow, cramped and quickly (or gratefully) forgotten.

Second, the proponent of such a list (that is, me) must review, reconsider or even reread works first encountered years or decades in the past. If the list does not help you, it may help me.

Third, the list makes us think why it is, exactly, we do what we do. The usual concepts – justice, productivity, money, honor – are not well-explored in the day-in, day-out of law practice.

A few caveats are in order.

First, this is a personal, idiosyncratic (or eccentric) list. If you want a survey course, go to a community college.

Second, I have made little effort to be “fair,” at least at that term is understood politically today. I have not tried to equally represent time periods, genres, genders or ethnicities. I realize that the list is populated with white males, most of whom are dead or will be soon. Could someone make a list of 13 books written by others? Very much so, and more power to them.

Third, a great many books are not eligible by my own fiat for this list. How so?

I have excluded all biographies and autobiographies of lawyers, even though there are some superb ones. Two that come to mind, for example, are Evan Thomas’s The Man To See (1992) (about Edward Bennett Williams) and Louis Nizer’s My Life In Court (1961).

I have also excluded all how-to books, even though there are a number of excellent ones. My favorite is Herbert J. Stein and Stephen A. Saltzburg’s Trying Cases to Win (2013) (one volume).

There is a lot of dreck written about white-collar criminals and the white collar “mind,” and it was for the most part a pleasure to exclude that sub-genre. Nevertheless, there are some admirable works including, very recently, Harvard Business School professor Eugene Soltes’s Why They Do It and Duke professor (and former Enron prosecutor) Sam Buell’s Capital Offenses.

Like the poet Dante, you have been warned before you enter the gates. Let us turn to 13 books that every white-collar lawyer should read.

Albert Camus, The Fall | Best known for The Stranger, French novelist Albert Camus (1913-1960) careens in and out of literary fashion. Admittedly, French existentialism is sometimes little more than navel-gazing with bad breath, but Camus at his best is incandescent (and, at his worst, is far better than Stalinist puppets like Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir).

The Fall (1956) is narrated by a disgraced lawyer sitting in a Dutch bar. His insights into how we fall from grace and face daily judgment are dark but powerful.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby | There is only a little bit of crime in The Great Gatsby (1925) : Jay turns out to be in the “numbers racket,” and Myrtle is the victim of vehicular homicide. The compelling white-collar aspect of this greatest of 20th-cntury American novels is its study of money and power, as the narrator, Nick Carraway, sets out in the opening:

When I came back from the East last autumn I felt that I wanted the world to be in uniform and at a sort of moral attention forever; I wanted no more riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart. Only Gatsby, the man who gives his name to this book, was exempt from my reaction — Gatsby, who represented everything for which I have an unaffected scorn. If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about him, some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life, as if he were related to one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away. This responsiveness had nothing to do with that flabby impressionability which is dignified under the name of the “creative temperament.”— it was an extraordinary gift for hope, a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person and which it is not likely I shall ever find again. No — Gatsby turned out all right at the end; it is what preyed on Gatsby, what foul dust floated in the wake of his dreams that temporarily closed out my interest in the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men.

Saint Paul, Letter to the Romans | On the road to Damascus, Saul famously became Paul. The most powerful of the Pauline letters is the one he wrote to the new Christians living in Rome. Even for the non-Christian or the secular, his analysis of law and grace is unparalleled, especially in chapter 7:

15 For I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. 16 Now if I do what I do not want, I agree with the law, that it is good. 17 So now it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me. 18 For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh. For I have the desire to do what is right, but not the ability to carry it out. 19 For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing. 20 Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me.

21 So I find it to be a law that when I want to do right, evil lies close at hand. 22 For I delight in the law of God, in my inner being, 23 but I see in my members another law waging war against the law of my mind and making me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members. 24 Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death? 25 Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord! So then, I myself serve the law of God with my mind, but with my flesh I serve the law of sin.

In our own law practices, we may ask of ourselves what we seek to understand about our clients: Who do we serve with our mind, and who do we serve with our flesh?

Scott Turow, Personal Injuries | As a novelist of popular law-oriented contemporary fiction, Turow towers over most others. His 1999 novel Personal Injuries is agonizing (and agonizingly familiar to white-collar lawyers) in its description of lawyer Robbie Feaver’s downfall. As Publishers Weekly noted at the time:

Unlike most of his fellow lawyer-novelists, Turow has always been more interested in character than plot, and in Robbie Feaver, a lawyer on the make who ends up fighting for his life, he has created his richest and most compelling figure yet. For years, Robbie has been paying off judges and squirreling away part of the riches he earns as a highly successful trial lawyer. When the IRS happens upon the money trail, and a top prosecutor leans on him to turn state’s evidence and finger some of the corrupt justices, Robbie calls on George Mason, veteran Kindle County lawyer, to represent him and win the best deal he can. A complicating element in the case is Evon Miller, Mormon-born FBI agent in deep undercover, who is assigned to watch Feaver and finds herself, against her better inclinations, drawn to him–for Feaver is a character of almost Shakespearean contradictions. A charming, brash womanizer who nevertheless shows superhuman reserves of love and patience to his dying wife at home, he is always several jumps ahead of the prosecutors, the FBI and the reader, winning sympathy, even admiration, where there should be none.

Read the full review here.

William Shakespeare, Macbeth | There are lots of lawyers, law-language and legal proceedings in Shakespeare’s work, but for the white-collar lawyer there is no match for Macbeth. Its themes of power, overreach, ambition and guilt form part of the Western consciousness and are timeless:

Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood clean from my hand? No, this my hand will rather the multitudinous seas incarnadine, making the green one red.

(Macbeth 2.2.57-60 — otherwise known as a Fed.R.Crim.P. 11 “colloquy”).

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment | What, exactly, to say about Crime and Punishment (1866)? As noted by translator David McDuff:

Few works of fiction have attracted so many widely divergent interpretations as Crime and Punishment. It has been seen as a detective novel, an attack on radical youth, a study in “alienation” and criminal psychopathology, a work of prophecy (the attempt on the life of Tsar Alexander II by the nihilist student Dimitri Karakosov took place while the book was at the printer’s, and some even saw the Tsar’s murder in 1881 as a fulfillment of Dostoyevsky’s warning), an indictment of urban social conditions in 19th century Russia, a religious epic and a proto – Nietzschean analysis of the “will to power.” It is, of course, all these things – but it is more.

Like all of us, Raskolnikov – the nihilist student who without any real reason kills an old woman – is guilty of original sin and saved, so to speak, only by suffering. What are the things that bring home to white-collar lawyers the notions of original sin and expiation by suffering? For me, they may be the first meeting with the client; or the second meeting with the client (when the omissions from the first meeting come out); or the decision to plead or go to trial; or the moment when the jury returns with a verdict.

For more on Dostoyevsky, see BBC Radio4’s In Our Time with Melvin Bragg and guests.

Craig Nova, The Good Son | White-collar lawyers often represent wealthy, powerful men (at least, they hope the people they represent are wealthy). Nova’s depiction of power and wealth, fathers and sons, is extraordinary. If anybody needed good counselors, it’s Nova’s white-collar people in The Good Son (1982).

From novelist John Irving’s 1982 review:

Pop MacKinnon – ”a coarse, charming man, a lawyer, and a good one” – wants his sons to follow his path: to be lawyers who know how to hunt and marry well; to be gentlemen who join that unassailable aristocracy which is earned by tough, no-nonsense cleverness and is protected by money. Son John disappoints Pop; he is killed in World War II. So son Chip – a fighter pilot who was shot down in the war but survived as a P.O.W. – becomes the title character of ”The Good Son,” Craig Nova’s fourth novel. In this dark, deep story of a father and son who love (and love to fight) each other, the good son is the one who will defeat, or even kill, his father with the father’s own weapons.

In this exquisitely delineated battle between father and son, both men are consumed and changed; each gets his own way but both victors pay a price. ”When my boys were younger I sent them to Yale,” Pop Mackinnon says, ”because I wanted all the nonsense knocked out of them. A passing appreciation of books and so on, but no more. I wanted my sons to have sensible ideas.” Pop means the law: ”because law is the thing, the most sensible of all, because it works like a boa constrictor, the best of all snakes. My favorite. A boa doesn’t actually squeeze anything. The snake just wraps itself around a man or a lamb or some unfortunate creature and waits for whatever it’s wrapped around to exhale: the boa then takes up the slack. It’s a procedure, and the law is nothing else if it’s not a procedure. You can trust a snake, especially a nice Harvard one, so that’s why, after the war (after having all the nonsense knocked out of him in New Haven) I sent Chip to law school in Cambridge.”

Read the entire review here.

Peter Taylor, “The Gift of the Prodigal” | Taylor was one of the best American short story writers of the 20th century, and “The Gift of the Prodigal” (published in the New Yorker in 1981 and included in Taylor’s 1996 collection The Old Forest and Other Stories) is a jewel. Narrated by an aging widower in Charlottesville, the short story turns the New Testament parable and has the prodigal, his son Ricky — twice-divorced and frequently in trouble with the law or lovers — bringing a gift to the father as none of his other grown children can.

James Ellroy, The Black Dahlia | Although Ellroy’s later work is sometimes frenetic and turgid, his earlier works – especially The Big Nowhere (1988) and The Black Dahlia (1987) – are taut, violent, overwhelming portraits of L.A. noir. The Black Dahlia is based on the 1947 murder of Elizabeth Short in Los Angeles. There are not many true “white collar” criminals in Ellroy’s early work, but few novelists set out the dark hearts of law-enforcement, prosecutors and defense lawyers better.

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago | With the demise of the Soviet Union, Solzhenitsyn has receded from the preeminence he had as a dissident, exile, novelist and philosopher in the 1970s. He was, however, one of the great moral figures of the 20th century. Now condensed into a more manageable one volume, The Gulag Archipelago (1973) describes the Soviet “gulags” – the prison camps for political prisoners and others – from the very beginnings of the Revolution to the 1950s. With Communism vanquished, we too often forget what totalitarianism really was. One of its characteristics is the pretense of law used to deprive people of liberty for the benefit of the state. We in the white-collar world are well advised to not forget the grim fact.

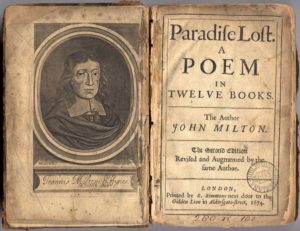

John Milton, Paradise Lost | In 1667, John Milton undertook to “justifye the wayes of God to men.” Rebellion and the fall, heaven and hell, perfect justice and marring sin — all remain as vibrant as they were centuries ago.

T.S. Eliot, Murder In The Cathedral | Murder In The Cathedral (1935) is a play in verse, not a book, but it made the list anyway.

Eliot, one of the great modern poets and the author of “The Waste Land,” deserves to read for this story of the Christmas Eve murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas a’ Becket:

Now is my way clear, now is the meaning plain:

Temptation shall not come in this kind again.

The last temptation is the greatest treason:

To do the right deed for the wrong reason.

And, of course, there is the 1964 film Becket with Richard Burton as the Archbishop of Canterbury and Peter O’Toole as King Henry II:

George V. Higgins, The Friends of Eddie Coyle | Nobody in American fiction did the dialogue of criminals, law-enforcement and lawyers better than George V. Higgins. Higgins, a one-time AUSA in Boston, apparently honed his craft early by listening to thousands of hours of undercover tape recordings. His first novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1970), is a foundation of contemporary crime fiction.

I have written before about Higgins here . . .

and also here . . .

Finally, I would be remiss if we did not watch the the wonderful trailer from the 1973 film starring Robert Mitchum as Eddie Coyle:

Here endeth the reading.