Why Innocent People Plead Guilty: Judge Rakoff, Eddie Coyle, Albert Camus and Sweet Dreams of Oppression

Reading Time: 10 minutes.

If they give awards for “Best White-Collar Article of The Year,” I wish to nominate one. And it’s not even, strictly speaking, an article only about white-collar crime.

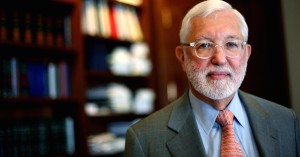

Jed Rakoff is a federal district judge in the Southern District of New York (in other words, in Manhattan). We have mentioned Judge Rakoff before, here and here. He also famously criticized DOJ’s failure, as he perceived it, to prosecute individual executives in the financial crisis.

Here, he has a thoughtful article on Why Innocent People Plead Guilty.

Portions bear quoting at some length:

The criminal justice system in the United States today bears little relationship to what the Founding Fathers contemplated, what the movies and television portray, or what the average American believes.

To the Founding Fathers, the critical element in the system was the jury trial, which served not only as a truth-seeking mechanism and a means of achieving fairness, but also as a shield against tyranny. As Thomas Jefferson famously said, “I consider [trial by jury] as the only anchor ever yet imagined by man, by which a government can be held to the principles of its constitution.”

The Sixth Amendment guarantees that “in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury.” The Constitution further guarantees that at the trial, the accused will have the assistance of counsel, who can confront and cross-examine his accusers and present evidence on the accused’s behalf. He may be convicted only if an impartial jury of his peers is unanimously of the view that he is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt and so states, publicly, in its verdict.

The drama inherent in these guarantees is regularly portrayed in movies and television programs as an open battle played out in public before a judge and jury. But this is all a mirage. In actuality, our criminal justice system is almost exclusively a system of plea bargaining, negotiated behind closed doors and with no judicial oversight. The outcome is very largely determined by the prosecutor alone.

Judge Rakoff explains why it is really the prosecutor, rather than the judge, who sets the sentence:

Judge Rakoff explains why it is really the prosecutor, rather than the judge, who sets the sentence:

[T]he information-deprived defense lawyer, typically within a few days after the arrest, meets with the overconfident prosecutor, who makes clear that, unless the case can be promptly resolved by a plea bargain, he intends to charge the defendant with the most severe offenses he can prove. Indeed, until late last year, federal prosecutors were under orders from a series of attorney generals to charge the defendant with the most serious charges that could be proved—unless, of course, the defendant was willing to enter into a plea bargain. If, however, the defendant wants to plead guilty, the prosecutor will offer him a considerably reduced charge—but only if the plea is agreed to promptly (thus saving the prosecutor valuable resources). Otherwise, he will charge the maximum, and, while he will not close the door to any later plea bargain, it will be to a higher-level offense than the one offered at the outset of the case.

In this typical situation, the prosecutor has all the advantages. He knows a lot about the case (and, as noted, probably feels more confident about it than he should, since he has only heard from one side), whereas the defense lawyer knows very little. Furthermore, the prosecutor controls the decision to charge the defendant with a crime. Indeed, the law of every US jurisdiction leaves this to the prosecutor’s unfettered discretion; and both the prosecutor and the defense lawyer know that the grand jury, which typically will hear from one side only, is highly likely to approve any charge the prosecutor recommends.

But what really puts the prosecutor in the driver’s seat is the fact that he—because of mandatory minimums, sentencing guidelines (which, though no longer mandatory in the federal system, are still widely followed by most judges), and simply his ability to shape whatever charges are brought—can effectively dictate the sentence by how he publicly describes the offense. For example, the prosecutor can agree with the defense counsel in a federal narcotics case that, if there is a plea bargain, the defendant will only have to plead guilty to the personal sale of a few ounces of heroin, which carries no mandatory minimum and a guidelines range of less than two years; but if the defendant does not plead guilty, he will be charged with the drug conspiracy of which his sale was a small part, a conspiracy involving many kilograms of heroin, which could mean a ten-year mandatory minimum and a guidelines range of twenty years or more. Put another way, it is the prosecutor, not the judge, who effectively exercises the sentencing power, albeit cloaked as a charging decision.

Why should you care about any of this? You haven’t tried heroin since the 1970s, much less sold it.

You should care because you likely do not consider yourself a criminal and would be be offended if someone in authority charged you publicly with being one. As Judge Rakoff puts it:

A cynic might ask: What’s wrong with that? After all, crime rates have declined over the past twenty years to levels not seen since the early 1960s, and it is difficult to escape the conclusion that our criminal justice system, by giving prosecutors the power to force criminals to accept significant jail terms, has played a major part in this reduction. Most Americans feel a lot safer today than they did just a few decades ago, and that feeling has contributed substantially to their enjoyment of life. Why should we cavil at the empowering of prosecutors that has brought us this result?

* * * *

First, it is one-sided. Our criminal justice system is premised on the notion that, before we deprive a person of his liberty, he will have his “day in court,” i.e., he will be able to put the government to its proof and present his own facts and arguments, following which a jury of his peers will determine whether or not he is guilty of a crime and a neutral judge will, if he is found guilty, determine his sentence. As noted, numerous guarantees of this fair-minded approach are embodied in our Constitution, and were put there because of the Founding Fathers’ experience with the rigged British system of colonial justice. Is not the plea bargain system we have now substituted for our constitutional ideal similarly rigged?

Second, and closely related, the system of plea bargains dictated by prosecutors is the product of largely secret negotiations behind closed doors in the prosecutor’s office, and is subject to almost no review, either internally or by the courts. Such a secretive system inevitably invites arbitrary results. Indeed, there is a great irony in the fact that legislative measures that were designed to rectify the perceived evils of disparity and arbitrariness in sentencing have empowered prosecutors to preside over a plea-bargaining system that is so secretive and without rules that we do not even know whether or not it operates in an arbitrary manner.

Third, and possibly the gravest objection of all, the prosecutor-dictated plea bargain system, by creating such inordinate pressures to enter into plea bargains, appears to have led a significant number of defendants to plead guilty to crimes they never actually committed. . . . . [T]his self-protective psychology operates in noncapital cases as well, and recent studies suggest that this is a widespread problem. For example, the National Registry of Exonerations (a joint project of Michigan Law School and Northwestern Law School) records that of 1,428 legally acknowledged exonerations that have occurred since 1989 involving the full range of felony charges, 151 (or, again, about 10 percent) involved false guilty pleas.

When a defendant enters a plea in federal court, the judge asks him or her questions about the defendant’s acknowledgment of guilt. This process is called a “colloquy” under Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. The court must assure itself that “there is a factual basis for the plea” and that “the plea is voluntary and did not result from force, threats, or promises (other than promises in the plea agreement).”

But in a system where, as Judge Rakoff puts it, “it is the prosecutor, not the judge, who effectively exercises the sentencing power, albeit cloaked as a charging decision,” what constitutes “force”? Who defines “threats”?

Usually, Rule 11 colloquies are perfunctory, although occasionally the pleading defendant balks entirely, and the plea goes out the window.

Rarely, though, you get some actual discussion, as with a former Bechtel executive, accused of taking millions of dollars in kickbacks from energy companies, who entered a guilty plea last week:

During the hearing, Judge Deborah K. Chasanow asked Mr. Elgawhary if he was entering the plea because of threats against him or his family. Mr. Elgawhary laughed. “Not at all,” he said.

“Tell me why that caused that reaction?” the judge asked.

“I just want to…ease the life of my family.” he responded

“So you are pleading guilty because you are acknowledging your responsibility and this is the best you think you are going to do for minimizing impact on other people you care about?”

But had anyone threatened him with harm, the judge asked, or was the pressure he felt just from the charges themselves?

“It’s the fact that the charges are there and I don’t want to pay something more,” he said. “Let us stop here and deal with it”

Pressing further, the judge asked: “The pressure you feel comes from the charges themselves, is that correct, and not because someone else is putting any pressure on you to plead guilty?”

“Most likely, you honor,” Mr. Elgawhary said.

A plea often comes with a Government price-tag known as “cooperation.” The Economist makes a similar point about prosecutors-on-steroids and “cooperating” witnesses in The kings of the courtroom: How prosecutors came to dominate the criminal-justice system:

Another change that empowers prosecutors is the proliferation of incomprehensible new laws. This gives prosecutors more room for interpretation and encourages them to overcharge defendants in order to bully them into plea deals, says Harvey Silverglate, a defence lawyer. Since the financial crisis, says Alex Kozinski, a judge, prosecutors have been more tempted to pore over statutes looking for ways to stretch them so that this or that activity can be construed as illegal. “That’s not how criminal law is supposed to work. It should be clear what is illegal,” he says.

The same threats and incentives that push the innocent to plead guilty also drive many suspects to testify against others. Deals with “co-operating witnesses”, once rare, have grown common. In federal cases an estimated 25-30% of defendants offer some form of co-operation, and around half of those receive some credit for it. The proportion is double that in drug cases. Most federal cases are resolved using the actual or anticipated testimony of co-operating defendants.

Co-operator testimony often sways juries because snitches are seen as having first-hand knowledge of the pattern of criminal activity. But snitches hoping to avoid draconian jail terms may sometimes be tempted to compose rather than merely to sing.

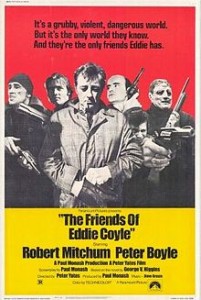

As Robert Mitchum said in The Friends Of Eddie Coyle (1973): “If I give you this, I can’t do no time.”

Here is an excerpt from our earlier take on all things Eddie Coyle, the worn-out cooperator (or snitch): George V. Higgins and the Archeology of White-Collar Crime:

In popular culture, business-crime is presented cartoon-fashion. In movies, on television or in novels, businesspeople who are corporate targets of government investigations come across as Snidely Whiplashes with French cuffs. This practice is predictable, its results boring. Not so with the work of the late Boston-based novelist and one-time Assistant United States Attorney George V. Higgins (1939 – 1999).

(Read the rest of the post here).

If plea-bargaining and press-ganged cooperation are two legs of the devil’s stool for white-collar defendants, the third leg is the evaporation of the presumption of innocence, a point we made in a post about Independence Day:

[T]he “presumption of innocence” about which we all learned (or, at least, used to learn) in civics class has been translated into a presumption of guilt. Most citizens, most of the time, believe that when a person or company is charged with a criminal offense, they are guilty (or perhaps guilty of something pretty close to the charged offense). (We have discussed presumption problems here and here).

In real life, how do I tell a client to not put very many eggs in the presumption-of-innocence basket?

To a businessperson or a professional, I say something like this:

“Imagine that you’re at breakfast one morning and see a news item. The news item says that someone has been arrested and charged with running a meth lab. To the extent you think about it at all, what do you think? You think the guy’s most likely guilty and was in fact running a meth lab, or do you think that he’s most likely innocent and is being falsely charged?”

I pause, watch it sink in and go on:

“Now, consider the guy who runs the meth lab. He sees a news item at breakfast that a banker has been charged with fraud; or a doctor has been charged with taking kickbacks; or a defense contractor has been charged with false billing. To the extent he thinks about it all, does he think that the banker or the doctor or the defense contractor is most likely innocent or most likely guilty?”

I realize that “most likely” is, technically speaking, not the standard in a criminal case. A discussion about the presumption of innocence cannot meaningfully proceed, however, without an appreciation of what I’ve come to realize over the years: jurors did not really apply (and sometimes do not even understand) the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard.

Rather, jurors apply what I call “preponderance plus.” By “preponderance plus,” I mean that they apply the “more likely than not” standard used in civil cases, and then they tighten it. In everyday conversation, we and they use “most likely” constantly, and the words mean something. When was the last time you used the phrase “beyond a reasonable doubt” outside of a legal discussion?

So what, if anything, is to be done?

I love Judge Rakoff’s proposal to involve judges in the plea-bargaining process, but that is unlikely to happen.

Perhaps the tonic needed is the self-knowledge articulated by Clamence, the protagonist of Albert Camus’s The Fall (1956): “I was a lawyer before coming here. Now, I am a judge-penitent.”

The truth is that every intelligent man, as you know, dreams of being a gangster and of ruling over society by force alone. As it is not so easy as the detective novels might lead one to believe, one generally relies on politics and joins the cruelest party. What does it matter, after all, if by humiliating one’s mind one succeeds in dominating every one? I discovered in myself sweet dreams of oppression.