George V. Higgins and the Archeology of White-Collar Crime

Reading Time: 3 minutes.

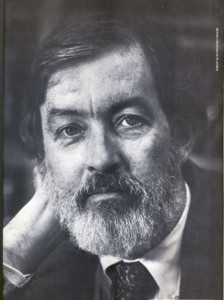

In popular culture, business-crime is presented cartoon-fashion. In movies, on television or in novels, businesspeople who are corporate targets of government investigations come across as Snidely Whiplashes with French cuffs. This practice is predictable, its results boring. Not so with the work of the late Boston-based novelist and one-time Assistant United States Attorney George V. Higgins (1939 – 1999). From the George V. Higgins Collection at the University of South Carolina:

George V. Higgins (1939-1999) succeeded in nine distinct careers, all of which are documented in his archive. Armed with two English degrees and a law degree, Higgins became a journalist for the Associated Press, The Boston Globe and The Wall Street Journal, as well as a federal prosecutor, district attorney and defense attorney, novelist, critic, historian and a creative writing professor at Boston University (1988-1999). He was also a fierce Red Sox loyalist, so much so that he wrote a book on Boston baseball in 1989 titled The Progress of the Seasons: Forty Years of Baseball in Our Town.

Here’s a collection of articles about Higgins: the NYT on George v. Higgins

What distinguishes Higgins, above all else, is voice. The term is “voice” is both over-used and under-used: over-used, when the critic means something like “tone.” Under-used, when the meaning conveyed is “narrator.” With the lawyers, crooks, businessmen and prosecutors of a Higgins novel, “voices” means actual “voices” — the sounds that one immediately recognizes as true, as here from Wonderful Years, Wonderful Years (1988), where a lawyer advises his client:

“‘You take your victim as you find him,'” Morse said.

“What?” Farley said.

“It’s a law thing,” Morse said. “You run over an eighty-year-old derelict with your car, no living relatives, and kill him. It’s not gonna cost you anywhere near as much, you hit a thirty-year-old brain surgeon with four kids and a wife and the only injury he suffers is the loss of his right hand. You didn’t pick your victim right, and so it’s gonna cost you. Sounds kind of mean, but that is the law. And the law’s fuckin’ life — so they say.”

Doubtless, Higgins can be difficult to read: a torrent of dialogue, and common, barely-linked events. Higgins’s novels are not thrillers, nor mysteries. Not only do they lack suspense, some barely have a plot. The best two in my experience are The Friends of Eddie Coyle (his first one) and Wonderful Years, Wonderful Years.

Higgins was also adept at describing the dynamic of business-crime prosecution, politics and disloyalty. Here, again from Wonderful Years, Wonderful Years, is a portion of a conversation between Saxon, a criminal-defense lawyer, and Farley, the owner of a Boston paving company and the target of a federal investigation. (For our younger readers, “Bobby” is Robert F. Kennedy):

“Now,” he said, “you’re telling me, these federal guys might do that? I must be getting old. This used to be America. What a rotten bunch of pricks.”

“Don’t kid yourself,” Saxon said. “They are a bunch of pricks. But they’re no worse’n the rotten bunch of pricks that Bobby’s men, and Ike’s appointments, FDR’s and Truman’s, all of those guys were. They all did the same damned thing. Suited them to crucify someone because the public’d like it, well, the next sound you hear’ll be the carpenters at work. War is the extension of diplomacy by other means? Justice is quite often the extension of politics by prosecution.”

“Well,” Farley said, “guess all I can do now’s hope she [his wife] keeps a good grip on her marbles, this whole shitty thing blows over.”

“That,” Saxon said, “and that nobody else in your little entourage gets cold feet and lets you down.”

“Never happen,” Farley said. “My people are loyal.”

“Right,” Saxon said. “That’s what Jesus thought. ‘Have a piece of bread, Judas. ‘Nother cup of wine? Nothing like a little supper with your friends all by your side.'”

The lawyer has his theology wrong — Jesus knew exactly what Judas was about — but that conversation likely happens in law offices somewhere each and every day.