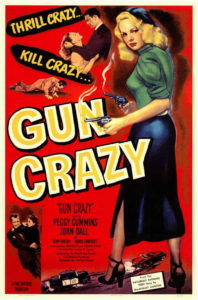

White-Collar Motive, Gun Crazy Movie

Reading Time: 6 minutes.

In 1950, producers Frank and Maurice King released Gun Crazy, a sometimes surreal Bonnie-and-Clyde story with an introverted, pacifist gun lover (Barton Tare, played by John Dall) and an English femme fatale sharpshooter (Annie Laurie Starr, played by Peggy Cummins). Carried forward by his lust for and fascination with Annie, the non-violent Bart — without thinking or planning — becomes a robber and, eventually, an accessory to murder.

A classic American film noir, Gun Crazy has merited a book (Eddie Mueller’s Gun Crazy: The Origin of American Outlaw Cinema) and much commentary by film buffs. It also gives us insight into a common question in white-collar cases: “Why did he [or she, but usually he] do it?”

The question of motive in white-collar cases is not an idle one but, rather, has implications for how prosecutors charge; how juries hear evidence; how defense lawyers defend; and how judges sentence.

But first, a little about this very strange, very cool movie.

The bank heist sequence was shot entirely in one long take in Montrose, California, with no one besides the principal actors and people inside the bank alerted to the operation. This one-take shot included the sequence of driving into town to the bank, distracting and then knocking out a patrolman, and making the get-away. This was done by simulating the interior of a sedan with a stretch Cadillac with room enough to mount the camera and a jockey’s saddle for the cameraman on a greased two-by-twelve board in the back. [The director] kept it fresh by having the actors improvise their dialogue.

In other words, when actor John Dall hopes aloud that there is parking place, he isn’t kidding: other than the people inside the bank, nobody knew that there was a movie being made or a bank robbery about to be staged, and no parking space had been reserved.

And what is the point of this for us white-collar readers?

The point is that almost nobody starts out to be a white-collar offender, any more than Bart starts out to be a bank robber. People rarely say on Monday: “Note to self – commit mail fraud by the end of the week.” The question is less one of “intent” and more one of “motive.”

Academic analysis bears upon the question of motive in ways inconsistent with popular thinking. Consider Harvard Business School professor Eugene Soltes, from the introduction to his fine volume Why They Do It: Inside the Mind of the White-Collar Criminal (2016):

Many people, federal prosecutors, scholars, and media commentators claim that executives make decisions, including criminal ones, through explicit cost – benefit calculation. Although such deliberate reasoning is consistent with the way many business decisions are made, this exclamation seems that odds with how these former leaders made the choices that eventually led them to prison. Mini we’re not mindfully weighing the expected benefits against the expected costs. If they had been, even the remote chance of being caught and sent to prison, upending their otherwise comfortable lives, would have weighed heavily on their conscience. But I didn’t see this. Instead, I found that they expanded surprisingly little effort deliberating the consequences of their actions. They seem to have reached their decisions to commit crimes with little thought or reflection. In many cases, it was difficult to say that they had ever really “decided” to commit a crime at all.

The prevailing ideas around reducing white – collar criminality rely on the assessment that executives are reasoning and calculative when they decide to commit and illegal act.

The emphasis on viewing cost – benefit analysis as a psychological model of choice rather than as simply a description of behavior has led to a particular notion of why once successful and intelligent executives commit white – collar crime long – namely, that these executives make thoughtful and deliberative calculations to break the law when doing so serves their needs and desires. They are not making hasty decisions with clouded judgment. Their personal failure lies in reasoning that the illicit choice is the ” appropriate” one.

[T]he trouble with this theory is that it doesn’t seem to match especially well with how executives who engage in white-collar crime actually think.

Why does this matter?

After all, many people (and almost all prosecutors) would argue that the “why” of things does not matter in the criminal context. In other words, they say, although “intent” is relevant, “motive” is not. The only important question, under this approach, is whether the person charged had sufficient “culpable intent” or a “guilty mind.” Under this view, “motive” is neither inculpatory nor exculpatory, even though the Federal Rules of evidence do allow, under certain circumstances, evidence to be admitted as proof of motive. (Consider Federal Rule of Evidence 404(b), which allows bad acts to be offered as evidence of motive).

But motive does matter. It matters for charging decisions. It matters for how juries hear evidence in the courtroom and how lawyers speak with them. And it matters for sentencing.

Prosecutors have discretion, as they should, with regard to whom to charge (and for what). If the cost-benefit model that Soltes describes is the governing lens through which a charging decision is made, then it is reasonable to expect that there will be over-charging (or at least more aggressive charging) as compared to an approach that, in a more nuanced fashion, appreciates the way business people actually make decisions. If I believe that your action is the result of a careful, cold cost-benefit analysis, I will conclude, other things being equal, that a more serious charge is due. As you sow, so shall you reap.

On the other hand, if I understand that rather than cost-benefit analysis what I am seeing is something more akin to business negligence, I may reasonably decide that a less serious charge (or no charge at all) is due. In Soltes’s words, if what I as the prosecutor see is “little effort deliberating the consequences of [one’s] actions,” I may think differently: after all, negligence, even gross negligence, is not normally the province of the criminal courts.

Motive colors the jury’s intake of evidence, and the prevailing zeitgeist of cost-benefit analysis works against the presumption of innocence (itself a largely extinct species, as I have discussed here and here and here.

Why is this so?

Distrust of business — and especially of large organizations, global institutions and the financial-services industry — is high among jurors across multiple demographics and political orientations. The caricature of the cold, calculating “fat cat” businessperson fits neatly with popular suppositions — and, sometimes, conspiracy theories — about business and finance. No amount of pretrial questionnaires or voir dire can address these deep-seated concerns with any regular success. At trial, the Government understandably seeks to tap into these veins of distrust and fear. And, once the jury hears at least some evidence confirming its initial biases, it is almost impossible, even for the most skilled defense lawyer, to turn them around.

On the other hand, if the jury rejects “cost-benefit” assumptions and believes that, in general, most white-collar defendants are not “reasoning and calculative” when they act (Soltes again), two things may happen.

First, the near-extinct presumption of innocence may be revived.

Second, if even some members of the jury conclude that the defendant was mindless (or just stupid), the chances increase that evidence offered by the Government will be examined more critically.

Sentencing

If cost-benefit analysis is a religion in white-collar cases, the fraud tables and the concept of “loss” in the federal Sentencing Guidelines constitute its liturgy. Were we to adopt a more realistic understanding of business decisionmaking in the context of white-collar offenses, we would reconsider the content and deployment of at least portions of the Guidelines.

The loss table in USSG 2B1.1.(b) is just math, a form of cost-benefit bracketing. The table attempts to impose a “cost” to a victim that it considers (or the Sentencing Commission considers) commensurate with a defendant’s “benefit.”

Laypersons are always surprised to learn that “loss” under the Guidelines does not mean “loss.” In fact, “loss” can mean “no loss.” (The dollar amount of loss to someone that the court believes the defendant “intended” to cause can be sufficient, even if there is no actual dollar loss to anyone). In a cost-benefit analytical regime, this idea of notional loss may be tolerable: we assume a calculation on the part of the business defendant and thus are more willing to accept a notional loss.

A more realistic view of business decisonmaking would go a long way towards restoring balance is an unbalanced white-collar system.

And, even if you disagree with me, you really should watch Gun Crazy.

Perhaps, like Annie, we all just “want things, a lot of things, big things.” The question is: When do we go to prison for it?