Global Cocktails, Glorious Funerals, and TSOP Moral Philosophy

Reading Time: 8 minutes.

Drinks seasonal and global, plus the popular “Drinks I Have Been Drinking.” Music for white-collar crime and stirring funerals. An interview. The Sound of Philadelphia and the role of lucre.

Cocktails

Let’s take a two-part approach: a drink for Fall and examples of “Drinks I Have Been Drinking.”

A Drink for Autumn Leaves

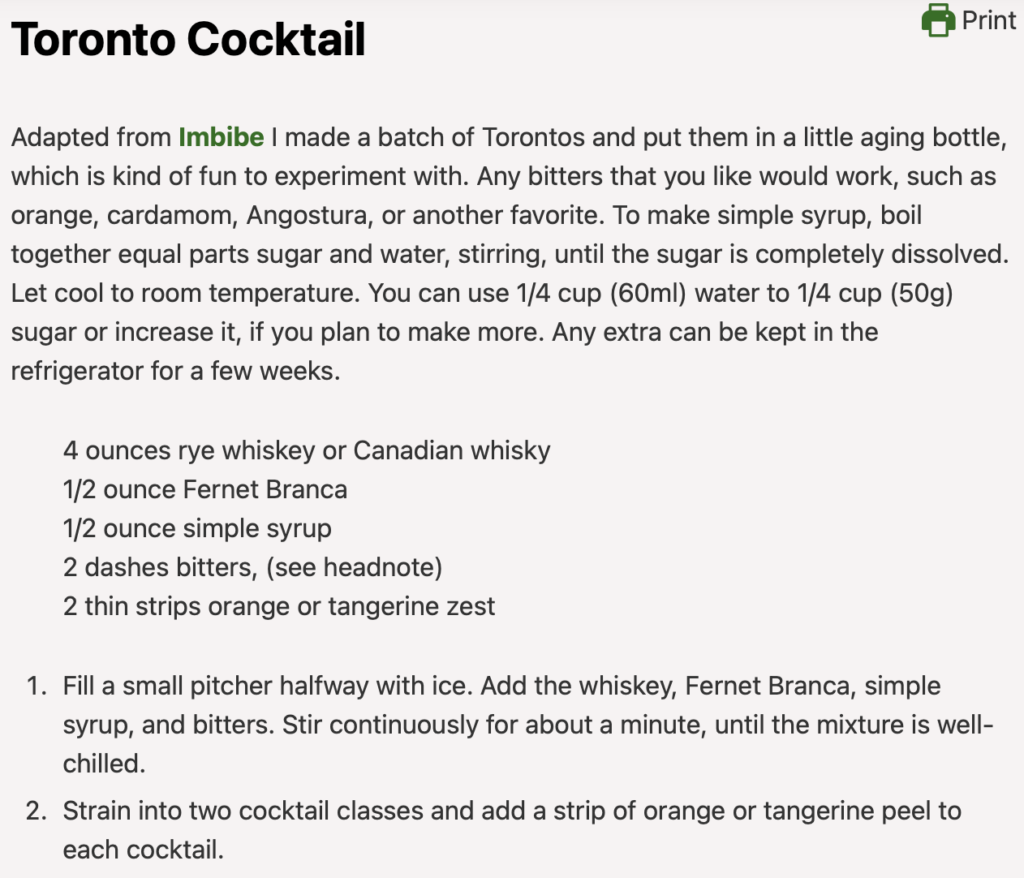

Autumn is upon us, at least in theory. The season puts one in mind for a Toronto cocktail:

Similar in construction to the earlier “Fernet Cocktail” appearing in Robert Vermier’s 1922 book, Cocktails: How to Mix Them, the Toronto is a spirit-forward Fernet-laced drink pulled from the pages of David A. Embury’s 1948 title The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks.

Punch, The Toronto

Punch’s recipe:

- 2 ounces rye

- 1/4 ounce Fernet-Branca

- 1/4 ounce demerara syrup

- 2 dashes Angostura bitters

Garnish: orange twist

DIRECTIONS

- Combine all ingredients in a mixing glass with ice and stir until chilled.

- Strain into a chilled coupe or cocktail glass.

- Garnish with an orange twist.

David Lebovitz has a similar recipe is his useful book Drinking French. The spec below is from his website:

“Drinks I Have Been Drinking”

Music

Music for white-collar crime and for funerals.

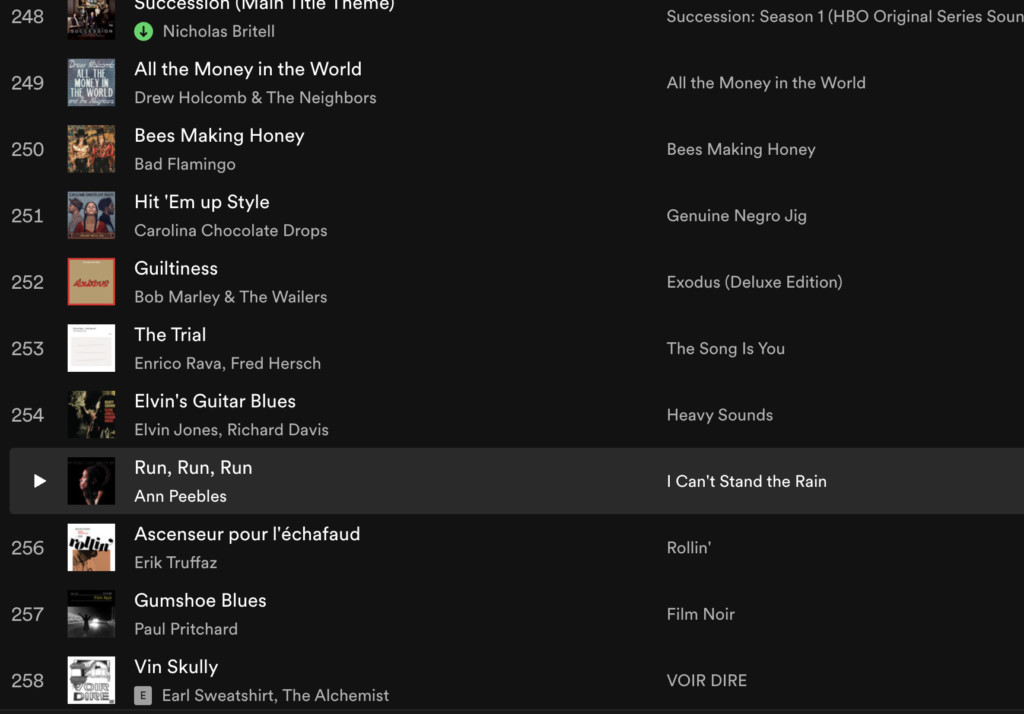

Loyal readers know that there is a White Collar Wire playlist on Spotify:

Recent additions include Earl Sweatshirt and The Alchemist just because I liked the title of the album (“VoirDire”):

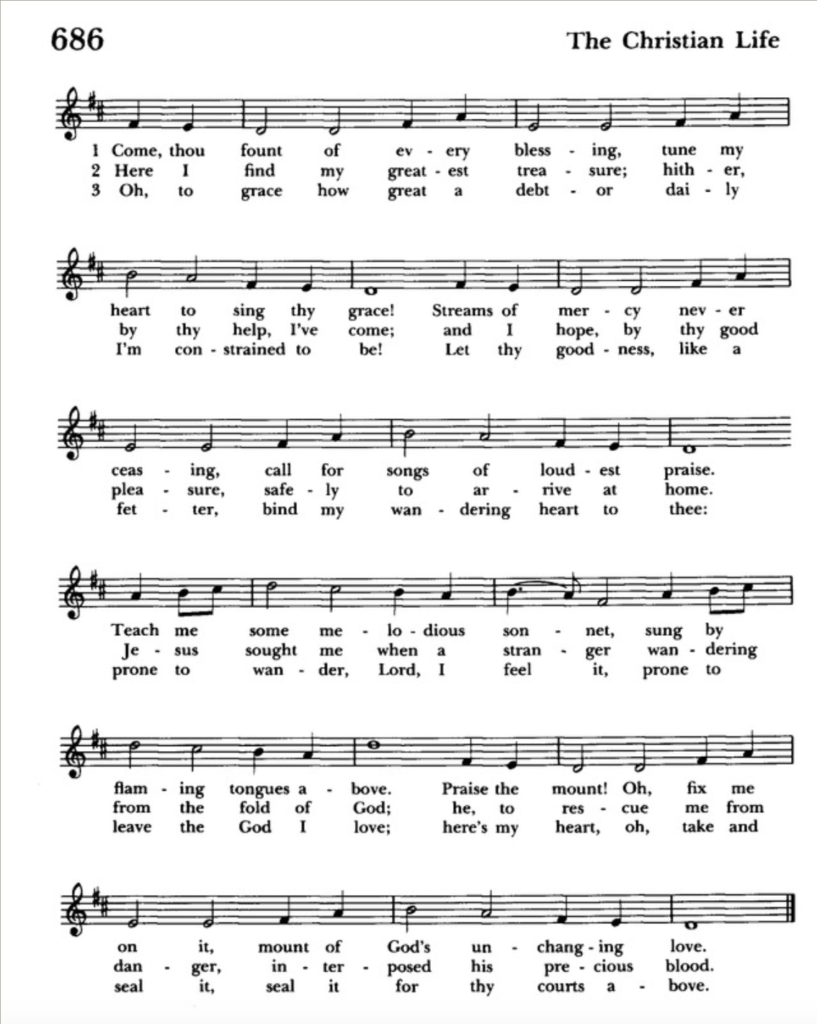

Perhaps it should be on the playlist, but I have already given instructions that Hymn 686 (“Come, thou fount of every blessing”) by Robert Robinson (1735-1790) be sung at my funeral:

Interview

I love to talk about some me. Below is a shortened version of an interview that appeared in the Network of Trial Law Firms’s newsletter.

Jack Sharman | Lightfoot, Franklin & White LLC

How do you describe your practice?

I represent corporations and individuals in white-collar criminal defense, internal investigations, and management of compliance risk.

Given the unique nature of a white-collar practice, what is your approach to client development?

White-collar work is a referral-driven business. We maintain a “top of mind” presence nationally, regionally, and locally. I publish in national trade journals and speak at industry programs. We do in-house CLEs for law departments. We host an annual “White-Collar Institute,” an event that gathers significant and interesting figures in the field—and I involve both partners and associates in all of these efforts. The goal is to always be in the conversation nationally.

What’s your approach to client service, and how does it set you apart?

In these areas, urgency is critical both as a practical matter (because the government is way ahead of you) and as a psychological matter (because the client is under unprecedented stress).

What are the biggest issues facing your clients right now?

At a high level, the possibility of an indictment – let alone a conviction – is always a looming concern for my corporate clients. For individuals, their biggest concerns are the prospect of prison, loss of career, and, as applicable, the dissolution of their marriage.

Business people and professionals can get into hot water today in ways they probably would not have 25 or 30 years ago. When I’m given the opportunity to provide proactive advice, I tell my clients that it doesn’t matter what we think of ourselves; what matters is what the investigators and prosecutors think of us. If they perceive us as acting wrongfully, then we have a problem, whether we are actually doing anything wrong or not. That’s why risk management is such an important issue in contemporary businesses.

Are there particular legal issues you’re monitoring or that you see heating up?

Prosecutors push the envelope in terms of what’s considered criminal conduct and seem more willing now than in the past to criminalize the provision of legal advice. We’re seeing more litigation about the crime-fraud exception to attorney-client privilege. There are some significant First and Sixth Amendment cases. The line between unethical conduct and criminal conduct is increasingly blurry.

The continuum of how business conduct is treated – whether it is considered perfectly ethical, lawful but unethical or unsettling, in violation of civil laws, or criminal conduct – has also become compressed in the eyes of Congress, the public (and hence jurors), and even judges.

How would you describe your ideal client?

A solvent corporation or wealthy individual in deep trouble.

What made you decide to become a lawyer?

After graduating from Washington and Lee with a double major in politics and French, I obtained an MFA in Fiction at Washington University in St. Louis. I then received a Rotary scholarship to the Institute for European Studies in Geneva, Switzerland, where I earned a certificate in European studies.

Unfortunately, after investing three years in those two degrees, there still weren’t many opportunities to generate income, so I went to law school at Harvard. Law school was a practical decision that worked out well.

Tell me about one of the most interesting cases you’ve handled.

Two recent matters stand out: serving as Special Counsel to the Alabama House Judiciary Committee for the impeachment investigation of Governor Robert Bentley and serving as Special Counsel in several matters related to the 2020 presidential election.

I was originally appointed to assist the Office of the Secretary of State of Georgia, Secretary Raffensperger, and his staff in dealing with the Fulton County District Attorney investigation into the 2020 election. That led to serving as Special Counsel for the January 6 Congressional investigation, followed by the Office of Special Counsel DOJ investigation, and now we’re back to the Fulton County matter again with the grand jury indictment. It’s been engaging and fun to be part of such historic matters.

I’ve also done some interesting work in the wake of George Floyd’s death, including reviewing a police department. Looking farther back, I was Special Counsel to the House Financial Services Committee for the Whitewater investigation.

You’re a prolific writer and have built a reputation for clever and edgy content. What led you to start your blog, White Collar Wire, and how has it evolved?

Even the most successful white-collar practice has few repeat clients – there’s only so many times a company or individual can be indicted – so a modest amount of hustle and branding is necessary. The blog is one way to accomplish that. Plus, I like writing and cocktails.

Decision makers looking to retain a “hired gun” like me have a lot of choices, so the blog is one way I can stay top of mind and be part of the discussion. I don’t need 500,000 followers; I need a handful of the right followers.

How much of your career has been at Lightfoot?

I’ve been with the firm for 28 of my 33 years in practice. I grew up in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, then went away to college, graduate school, and law school; clerked in Washington for Judge David Sentelle on the D.C. Circuit; and worked at Covington & Burling for four years. Just as I was starting the Whitewater gig, Lee Hollis, whom I knew through my W&L alumni network, called with an enticing opportunity to join a group that had left a larger, full-service firm to start a litigation boutique.

Working at a big firm is kind of like being on a big ocean liner – you can jump up and down on the deck, but the boat just keeps cruising. This was a chance to make waves with less red tape and fewer impediments to entrepreneurship, so Elizabeth and I moved to Alabama in 1995.

What do you consider Lightfoot’s key differentiators? How do you distinguish the firm from its competitors?

Shane Parrish from the Farnam Street blog noted recently that one contributing factor to differentiation is the ability to see the same thing that others see but to see it differently. Lightfoot lawyers are remarkably adept at seeing things differently. Many times, success or failure depends wholly on that one ability.

From the time I arrived at the firm, I’ve been struck by people’s ability to do things in different ways and with different styles. We all approach matters differently and have different personalities, but the one thing we have in common is the ability to look at things in new and unique ways – in ways nobody’s thought of yet.

In addition to leading your firm’s White-Collar practice, you’re on your firm’s Recruiting and Marketing and Business Development Committees. What’s your trick to identifying talent?

I tend to pay the most attention to the people who are a little uncomfortable – not in terms of their abilities – but actually nervous about the interview because they have a lot going on. They have the intellectual firepower, personal energy, and ambition, so when you’re visiting with them, they’re very much alive – there’s an edge to them. And maybe that’s really it – they also see things differently, which gives them that edge. Everybody at Lightfoot, even though we’re all different, has a little bit of an edge to them.

What are some challenges you’re facing in recruiting attorneys and staff?

Like every other market, the market for legal talent is fractured, information-driven (and misinformation-driven), and less beholden to long-term loyalty. We see this on the client-relations side, as well. At Lightfoot, we try to strike a balance between traditional expectations and contemporary realities.

In the past, the downtown bank wherever you were located was the client, and that was it. They were loyal to you, and you were loyal to them, and you’d have a decades-long relationship. Now there is more fragmentation, meaning less loyalty, in the market. I don’t mean that as sort of a moral criticism; it’s just the way the economy has played out.

Similarly, gone are the days when I was an associate and you would join a firm, settle in, and be there the rest of your career. Current law students and recent graduates have more opportunities in some ways because of their skepticism about the value of a long-term commitment, but that makes recruiting more challenging. We’re seeing more candidates signing on for multi-year clerkships with different federal judges, which means a summer associate who receives an offer may be three years away from actually joining the firm. After three years, your firm may be a distant memory.

Crime Fiction, Old Time Religion

More than a decade ago, at the Cathedral Church of the Advent in Birmingham, I taught a four-part class titled Red Harvest: Crime Fiction and Gospel Conviction:

On the audio, I sound younger, but the sessions have aged reasonably well.

The Root of All Evil

We are about white-collar crime at White Collar Wire. White-collar defendants have mixed motives, of course, but money is often in the mix. No one said it more succinctly than Philadelphia’s most noted moral philosophers, The O’Jays: