Christmas, Ghost

Reading Time: 3 minutes.

“Marley was dead: to begin with.” A Christmas Carol is, above all else, a ghost story. But what does a ghost have to do with you, a living woman or man, bedecked and harassed and very much alive on this Christmas Day?

Through the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, Christmas was deemed an appropriate time for tales of fear and unease. Part of the appeal perhaps harps back to pre-converted pagans at the winter solstice, when darkness and cold seem the most powerful spirits on the planet.

The dark and the cold still resonate with us in this season; perhaps my favorite Christmas hymn is “In the bleak midwinter” by Christina Georgina Rossetti (1830-1894).

In the Christian calendar, what many consider “Christmastime” is not really Christmas at all—pace Mariah Carey—but rather the season of Advent, a four-week reflection on the final four things: death, judgment, hell, and heaven. This season of reflection was intended to prepare the hearts of the faithful to receive the incarnate God, an event without equal before or repetition since—the rendering of the divine into infant flesh, an infant who is only purpose was to die, crucified for our sins.

Today, few dwell on the jarring significance of John Henry Hopkins, Jr.’s wonderful 1857 Christmas hymn “We Three Kings.” Gaspard brings gold, and Melchior brings frankincense, but Balthazar brings something different:

Myrrh is mine; its bitter perfume

Breathes a life of gathering gloom; —

Sorrowing, sighing,

Bleeding, dying,

Sealed in the stone-cold tomb.

John Henry Hopkins, Jr., “We Three Kings” (1857)

In the ancient world, myrrh was used for embalming. And after the empty tomb of his resurrection, Jesus promised his disciples that the Father would send them a helper, that person of the Trinity who came to be known in the King James Version of the Bible as the Holy Ghost.

It should not surprise us, nor is it inappropriate, that ghosts tug our sleeves at Christmas.

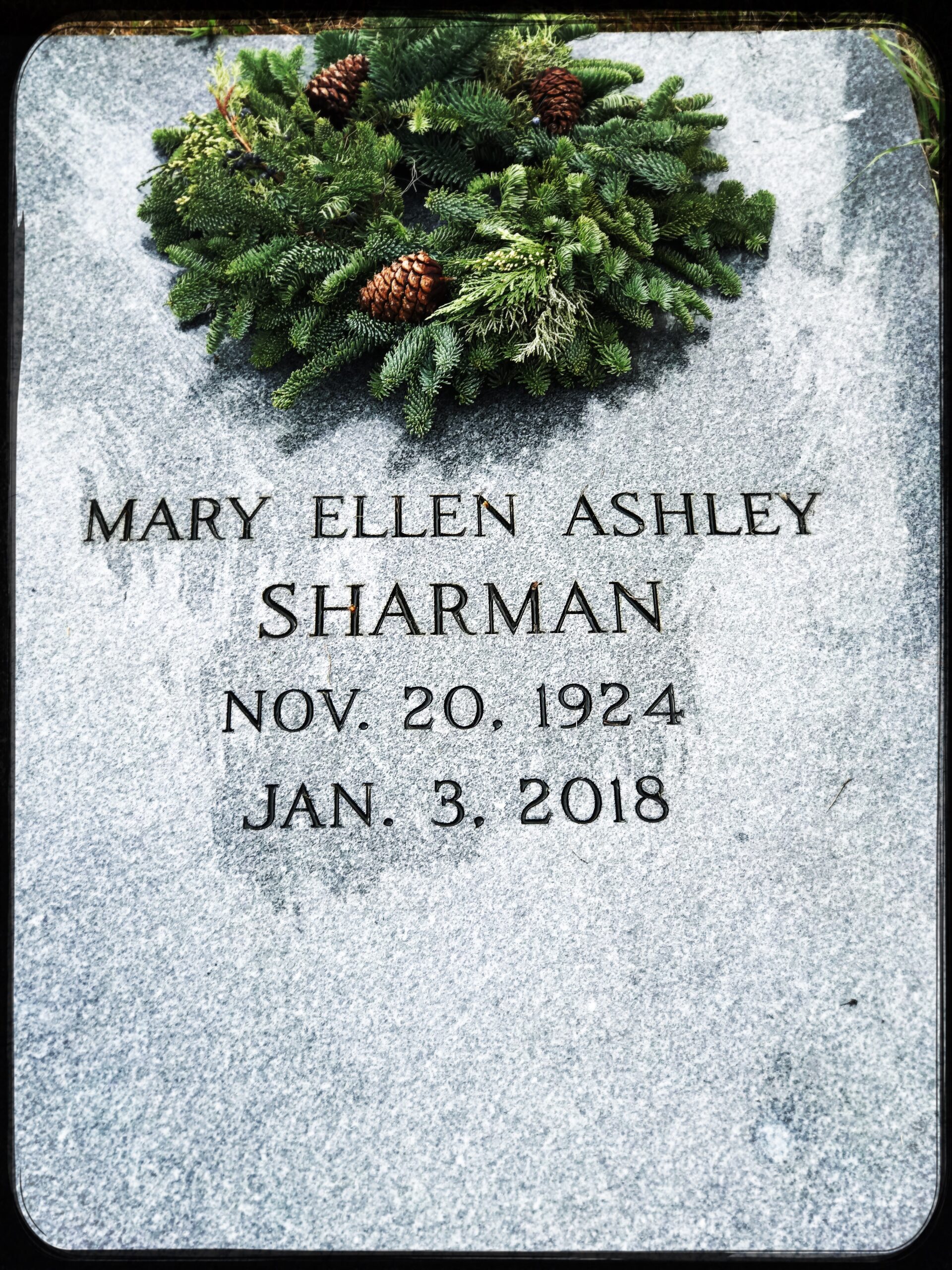

So it should not surprise us, nor is it inappropriate, that ghosts tug our sleeves at Christmas. I re-read A Christmas Carol this past week, and perhaps its ghostliness is one of its enduring charms. As Ebenezer Scrooge observed after the third “ghost” had left him: “The Spirits have done it all in one night. They can do anything they like. Of course they can.” Many of us remember the dead more at Christmas than at any other time of the year. (Or, at least, we do more about it than at any other time of the year). I place wreaths on my parents’ gravestones.

But Christmastime wreath-laying is for the living, not the dead. In rain and water and churned earth, in sunlight and dry winter wind, the wreath will disintegrate as surely as our bodies, simple pine needles and dry berries swept aside by the cemetery-caretaker’s broom. Wreath-laying is for remembrance, some memory-fragment of the departed, but it does not speak to the final four things. In a year of turmoil and plague, wreath-laying gives us pause, which is good, but it is not a salve. It speaks of memory, not eternity.

The only one who speaks to eternity is that Infant whose only purpose was to die for our sins. Someone observed that the prickly hay in the manger would have been a pricking premonition to infant flesh of the crude nails to come. Eternity is beyond our ken; the hard cold and the dark of the present are difficult enough. Death seems final; ghosts, like Jacob Marley, wander.

What does not wander is the birth of a savior and his death, standing in our stead. Christmas Day is full of mystery and joy, both tempered and driven home by the nails that drove through flesh, through the incarnate God, and splintered into the wood of the cross. This year’s plague and upheaval? Dislocation and separation? Loss and death? Splinters. He knew all of them, better than we. Take comfort and joy in that perfect knowledge on this, the most splendid day of the year.