Privilege, Corporate Silence and Saul Goodman

Reading Time: 4 minutes.

We are past Labor Day, and just as well. Marked by the GM internal-investigation report’s criticism of some of the company’s internal lawyers, the summer was not kind to internal lawyers generally and to the attorney-client privilege particularly. Consider, for example, the FCPA Blog‘s note on how life is tough for internal counsel.

Even more notably, there is apparently a federal criminal investigation of GM that includes the conduct of the lawyers:

Prosecutors could try to charge current and former GM lawyers and others with mail and wire fraud, the same charges Toyota faced, said a former official who worked on the Toyota case. But, they would need to have clear proof that the employees knew the cars were faulty and then deliberately withheld that, the former official said.

The investigation could be hindered by attorney-client privilege, according to legal experts, but that privilege can be waived by GM or pierced by a “crime-fraud” exception that allows disclosure of information intended to commit or cover up a crime or fraud.

The notion of privilege has taken a beating in recent weeks, as shown in a New York Times “Dealbook” article (Keeping Corporate Lawyers Silent Can Shelter Wrongdoing) by Steven Davidoff Solomon, a professor of law at the University of California, Berkeley:

[U]nless a whistle-blower steps forward, the [attorney-client privilege] principle remains strong. Despite the widespread involvement of its legal staff, General Motors successfully invoked the privilege to help keep silent on the ignition scandal it eventually faced. Even the Justice Department changed its guidelines in 2008 to remove a provision that penalized companies for invoking the privilege.

The result is that companies have a great incentive to shift anything hinting at legal trouble to their in-house counsel to ensure that it is protected from disclosure. The in-house legal department thus becomes the “cover-up and damage control” arm of the company.

. . . .

Is it time to cut back privilege or even end it to prevent companies from hiding corporate crimes?

And, here’s further commentary from Lucian E. Dervan at the White Collar Crime Prof blog, focusing on the Delaware Supreme Court opinion in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Indiana Electrical Workers Pension Trust Fund IBEW,Del. Supr., No. 614, 2013 (July 23, 2014): Privilege, Corporate Wrongdoing, and the Wal-Mart FCPA Investigation.

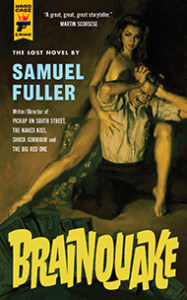

It’s enough to make a law-abiding internal lawyer (and even the supporting-cast outside counsel) feel like Walter White’s lawyer, Saul Goodman, in Breaking Bad:

What’s to be done?

Here are my thoughts in 140 seconds:

We have written on GM and the privilege before: How To Avoid Being GM’ed: The Wrongs and Rights of Clients and Lawyers. In particular:

It is by no means inconceivable that bills will be introduced seeking to impose, in GM-like situations, a Sarbanes-Oxley style “reporting” requirement on internal lawyers (or outside counsel, or both), coupled with a “private attorney general” concept and whistleblower bounties. As in the SOX, internal-investigation world, if the matter is sufficiently serious, you may need two law firms: one firm that does an investigation and prepares a report that we all know will end up in the hands of the Government, and one firm that provides advice to the company (or the board, or a committee of the board) and over whose work we hope to maintain privilege. We have addressed internal investigations and related problems before.

Indeed, it is instructive to compare the anti-privilege sentiment in its most pitchfork version with the recent decision of the D.C. Circuit in the KBR matter, which was a resounding reaffirmation of privilege in the internal-investigation context. As we pointed out in It’s Okay To Smell A Rat: Internal Investigations, Attorney-Client Privilege and the KBR Decision:

It is noteworthy that the D.C. Circuit clarifies the rule such that it applies in all contexts: civil, criminal and administrative. The attorney-client privilege is, to some degree, in derogation of the search for the truth, at least in the first instance. Yet, lawyers learn things from clients that the lawyers then do not have to reveal because we believe that, on balance, “truth” is ultimately best served in an adversarial system by a tool that encourages clients to tell their lawyers the truth.

This is an often overlooked point. Frequently, clients do not tell lawyers the whole truth, at least the first time a discussion arises. This is particularly the case in criminal representations, but it is not uncommon in the civil arena. Sometimes, this reticence arises from a client’s knowledge of his, her or its wrongdoing, and a concomitant desire to hide or destroy evidence.

More often, however, that initial reticence arises from much more innocuous sources: embarrassment, shame, misunderstanding, fear of losing a job or worry about how superiors or colleagues might react. In those contexts, it is the privilege itself that is most solicitous of the truth, and allows the truth to eventually out.

In fact, if you do smell a rat, sometimes there is all the greater need to speak in confidence:

The attorney-client privilege has engendered debate ever since its first articulation, and that debate is healthy. We should not let the urgency of news items, however, obscure the broader good that the privilege can serve. There are many things that, in our adversarial system, the Government does not get to know about my clients. We could change the system to a more inquisitorial structure, but such a move goes against a host of cultural and constitutional mindsets that, however imperfectly, have preserved individual liberties, property rights and the rule of law for a long time. There are few professional prospects more pleasant for a prosecutor or a regulator than an opportunity to strip you of the ability to speak in confidence to your lawyer.

As well-stated by Saul Goodman: