Dude, That’s My Lighter: Lacrosse, Suspensions, the Fourth Amendment and the White-Collar Thanatos of Zero Tolerance

Reading Time: 6 minutes.

The relationship between lacrosse and white-collar crime is not obvious, although for much of its 20th century history the sport was powered by mid-Atlantic and New England prep-school products whose high schools also provided several All-American rosters of white-collar defendants. And even for perfectly lawful activities, there has long been a close relationship between lacrosse and Wall Street, as shown in this 2008 Wall Street Journal article about how On Lacrosse Fields, A Battered Bank Is Still a Player

The story of how these Maryland lacrosse players’ case moves into court raises some curious insights, though, into matters of compliance and internal policing, not to mention Fourth and Fifth Amendment issues that can figure prominently in white-collar trials:

Families of two former Maryland high school lacrosse players have filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against school officials alleging that the teens were suspended for having dangerous weapons after an unconstitutional search of their equipment bags turned up two small knives and a lighter.

The lawsuit alleges that school officials in Talbot County, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, violated the students’ constitutional rights to due process and their protections against unreasonable search and seizure in 2011 when they boarded the team bus to investigate a tip about alcohol and took action against the teenagers for items the students said they used to maintain their lacrosse equipment.

The items were a lighter and a knife.

The suspensions were reversed by the state board of education, and the players filed a federal civil rights action:

The Maryland State Board of Education ruled against the school system in 2012 and ordered that the students’ records be cleared of the incident. The state’s decision was a rare reversal of student punishment and appeared to be in opposition to the zero-tolerance policies that have taken hold in schools across the country.

Lawyers with the nonprofit Rutherford Institute, a civil liberties advocacy firm, filed the lawsuit last month in U.S. District Court in Baltimore, seeking monetary damages from the Talbot County school board and four current or former school officials. It comes at a time when U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan has urged that out-of-school suspensions be used as a last resort for school-related incidents.

Before we recoil from the lighter and the knife, and begin to mutter about terrorism, consider this:

No alcohol was found, but during the search, Graham Dennis, then a 17-year-old junior, volunteered that he had a small knife, which he used to fix his lacrosse sticks, inside his gear bag.

School officials took the knife as well as a Leatherman tool they found and called police. The teenager was led away in handcuffs and suspended for 10 days.

A teammate, Casey Edsall, also a 17-year-old junior at the time, was suspended for having a lighter in his gear bag. The teenager said it was used to seal the frayed ends of strings on his lacrosse stick.

In its 2012 ruling, the Maryland board [i.e., the panel that reversed the school’s decision] said knives and lighters don’t belong at school but concluded that “this case is about context and about the appropriate exercise of discretion.”

The state board said the coaching staff had tacitly approved the use and possession of the items and that players had openly used them on the bus.

The facts are relatively obvious; their implications, less so.

First, students should not have lighters and knives at school.

Second, knives and lighters are frequently necessary to work on lacrosse heads and their stringing. For a YouTube video on the subject by a mildly-hungover guide, try YouTube Burning String Tips

Third, the school — through the actions of the coaches — approved the open use of knives and lighters on the bus.

The decision of the Maryland state school board is appropriate. For us, though, it is the board’s note about “context” and the “appropriate use of discretion” that is pertinent both for the thanatos of internal compliance and for the sometimes over-reaching character of white-collar criminal investigations and prosecutions.

(As a refresher: “Thanatos,” a minor Greek deity and the son of Nyx, was the personification of death. The word now refers to an impulse towards death or self-destruction).

First, both the sport and Wall Street have had bad press that at times have made them targets for politicians, activists and prosecutors of all stripes — sometimes with justification, sometimes not.

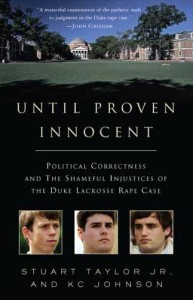

No doubt, lacrosse has had a tumultuous recent history, starting with the Duke lacrosse case in which players were falsely accused of rape.

That case ended with the prosecutor’s suspension and surrender of his license to practice law after an ethics complaint against him.

Separately, there was later a murder charge against the woman who falsely accused the Duke players, a charge of which she was convicted. More recently, a member of the University of Virginia men’s lacrosse team murdered a member of the Virginia women’s team.

Second, “zero tolerance” is an antonym to “context.” Context — the business, social, cultural and ethical landscape in which a person operates — is precisely what many compliance programs and white-collar investigations lack. As in the Maryland lacrosse-suspensions matter, a policy of “zero tolerance” is a often a cover for something else (especially the fear of civil, administrative or criminal liability) other than solicitude for the people, institutions or values that are offered in justification of the policy.

Third, an appreciation of “context” would introduce the concept of proportionality, whether externally (for example, in grand jury investigations) or internally (for example, in compliance-program investigations). The former investigations are distorted by the fact that many (perhaps most) of the folks at the levers of white-collar investigations have little or no experience of the industries, professions and services being investigated. Without such experience and context, it is understandable that one tends to see a Red under every bed.

The latter investigations are distorted by the business internal impulses and pressures under which they operate. A compliance investigation that leaves significant risk on the table is a failed compliance investigation.

In fairness, though, at times the internal compliance investigation can suffer from over-familiarity, and can fail to see the customary as also potentially criminal.

And, of course, there are plenty of actual criminals, some of them of distinguished pedigree, even if those investigating and accusing them are clumsy.

Fourth, just as we have an odd body of Fourth Amendment law within the schoolhouse door, we have too casual a view within the corporate boardroom of Fourth Amendment protections. Much as businesspeople shrink from asserting their Fifth Amendment rights, however wise such an assertion might be, they tend to think of the Fourth Amendment as the province of drug dealers, terrorists, pornographers and the faculty of Harvard Law School. Both views arise from the otherwise common-sense notion that, “if you have nothing to hide,” why not testify, or be searched? The “nothing to hide” rationale fails in the context of most white-collar crime, however, because what incriminates is intent, rather than the object or statement itself. A loan application can contain an error, or it can be a false statement. A check can be a commission or a kickback.

Such considerations come into play in most compliance and white-collar investigations, even those less important than burning the ends of the shooting strings on your lacrosse stick.

Dude.