Congressional Investigations, Criminal Cases and The Knights Who Say “Ni!”

Reading Time: 12 minutes.

We are heading into what appears to be a summer of investigations along the Potomac, some of them in the House and Senate. What are some of the things we might reasonably expect to see as investigations congressional and criminal cross paths? And what does Monty Python have to do with it?

Previously, I shared a few lessons about congressional investigations.

First, the short-version video:

Jack Sharman – Learning in Congress from Legal Filmworks Unlimited on Vimeo.

Second, a longer how-to approach for lawyers and clients in a congressional investigation:

In particular:

We are in the summer months. We have written before about summer hearings:

As a former oversight-and-investigations lawyer for a House committee, I can testify: summer is the high season for O&I hearings. Nothing is going on legislatively, O&I hearings don’t require lobbyists or constituents, it is hot as hell but most House and Senate hearing rooms have good air-conditioning these days and, if you get some hearings under your belt in June and July, you’ll have plenty as a Member to talk about in your district or state.

Because most people are familiar with Congressional investigations only through television, they assume that if they are caught up in an investigation they will be summoned to testify before a committee like John Dean or Oliver North, with cameras clicking amid vigorous partisan drama. Although your client may indeed be called to testify in a public hearing — and you should prepare as though your client will be called — it is more likely that constraints of time, the demands of the media, and political pressure and compromise having little to do with your client will result in your client never being called. If your client testifies, remember that in many instances the committee members’ “questions” are not actually designed to elicit information from the witness. Rather, questioning is often more like speech-making designed to maximize camera time on the questioner or to score political points against the opposition.

These lessons were reinforced in my latest job in this arena: Special Counsel to the Alabama House Judiciary Committee for the impeachment investigation of Governor Robert Bentley.

Talk of President Trump and impeachment seems to have subsided for the moment with the appointment of former FBI Director Robert Mueller as a Special Counsel to investigate potential links between the Russian government and the Trump campaign.

What are some points to keep in mind as these investigations — congressional and criminal — move down their parallel tracks?

The Grand Jury Is Grand. The criminal investigators will largely call the shots. How so?

There are two reasons that there will likely be increased negotiation and tension between Congress and the Special Counsel.

Telling Tales. The first reason is one common to all federal criminal investigations: no prosecutor wants his or her witnesses making statements, especially public statements under oath. Sworn statements lock the witness into a story and can be used by defense counsel for cross examination in a potential criminal trial.

Federal Knights Who Say “Ni!” The second reason is that, much like the terrifying “Knights Who Say ‘Ni!'” in the 1975 film Monty Python and The Holy Grail who look down upon the coconut-slapping Knights of the Round Table, federal prosecutors do not usually hold congressional investigators in high esteem although they convey that view with varying degrees of politeness. (Of course, I have expressed a differing view, sometimes with varying degrees of politeness). I learned this lesson both from my Whitewater time as Special Counsel to the House Financial Services Committee for the investigation of President and Mrs. Clinton’s dealings with Madison Guaranty and also from the recent impeachment investigation of Alabama Governor Robert Bentley.

INCENTIVE NOTE: If you make it to the end of this post, there is a “Knights Who Say ‘Ni!'” clip.

This clash between prosecutors and congressional investigators should not be too surprising. Congressional investigations and grand jury investigations serve different institutional and constitutional mandates. From time to time, there will be some tension.

Immunity? Congress could bugger up the criminal investigation by granting General Michael Flynn (or other witnesses) immunity in exchange for their testimony. As noted by Philip Shenon in Politico, after the Iran-Contra prosecutions of Colonel North and Admiral Poindexter, that is unlikely to happen:

The special prosecutor was convinced that Congress was on the verge of sabotaging his politically charged investigation—one that led straight into the White House and threatened to end with a president’s impeachment. And so he went to lawmakers on Capitol Hill with a plea: Do not grant immunity to witnesses in exchange for their testimony if you ever want anyone brought to justice.

But the plea failed. And the special prosecutor, Lawrence Walsh, a former federal judge appointed in 1986 to investigate the Iran-contra affair during the Reagan administration, watched two of his highest-profile targets go free: former National Security Adviser John M. Poindexter and Poindexter’s deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North. Although both former Ronald Reagan aides were later convicted at trial of multiple felonies, the convictions were overturned, with appeals courts deeming the prosecutions tainted as a result of the testimony the men had given to Congress with grants of supposedly limited immunity.

Read the full article: How Congress Could Cripple Robert Mueller.

As a reminder: a grant of congressional immunity raises a potential “Kastigar” problem for a criminal prosecutor. As the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit said in United States v. North:

Because the privilege against self-incrimination “reflects many of our fundamental values and most noble aspirations,” Murphy v. Waterfront Comm’n, 378 U.S. 52, 55, 84 S. Ct. 1594, 1596, 12 L. Ed. 2d 678 (1964), and because it is “the essential mainstay of our adversary system,” the Constitution requires “that the government seeking to punish an individual produce the evidence against him by its own independent labors, rather than by the cruel, simple expedient of compelling it from his own mouth.” Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 460, 86 S. Ct. 1602, 1620, 16 L. Ed. 2d 694 (1966).

The prohibition against compelled testimony is not absolute, however. Under the rule of Kastigar v. United States, 406 U.S. 441, 92 S. Ct. 1653, 32 L. Ed. 2d 212 (1972), a grant of use immunity under 18 U.S.C. § 60021 enables the government to compel a witness’s self-incriminating testimony. This is so because the statute prohibits the government both from using the immunized testimony itself and also from using any evidence derived directly or indirectly therefrom. Stated conversely, use immunity conferred under the statute is “coextensive with the scope of the privilege against self-incrimination, and therefore is sufficient to compel testimony over a claim of the privilege…. [Use immunity] prohibits the prosecutorial authorities from using the compelled testimony in any respect….” Kastigar, 406 U.S. at 453, 92 S. Ct. at 1661 (emphasis in original). See also Braswell v. United States, 487 U.S. 99, 108 S. Ct. 2284, 2295, 101 L. Ed. 2d 98 (1988) (“Testimony obtained pursuant to a grant of statutory use immunity may be used neither directly nor derivatively.”).

When the government proceeds to prosecute a previously immunized witness, it has “the heavy burden of proving that all of the evidence it proposes to use was derived from legitimate independent sources.” Kastigar, 406 U.S. at 461-62, 92 S. Ct. at 1665. The Court characterized the government’s affirmative burden as “heavy.” Most courts following Kastigar have imposed a “preponderance of the evidence” evidentiary burden on the government. See White Collar Crime: Fifth Survey of Law-Immunity, 26 Am.Crim.L.Rev. 1169, 1179 & n. 62 (1989) (hereafter “Immunity”). The Court analogized the statutory restrictions on use immunity to restrictions on the use of coerced confessions, which are inadmissible as evidence but which do not prohibit prosecution. Kastigar, 406 U.S. at 461, 92 S. Ct. at 1665. The Court pointed out, however, that the “use immunity” defendant may “be in a stronger position at trial” than the “coerced confession” defendant because of the different allocations of burden of proof. Id.

Constitutional Theater. Congressional investigations, in part, are political theater. That’s okay. As we have noted elsewhere:

The fact that there appear to be no rules in a congressional investigation underscores perhaps the primary fact that counsel should bear in mind: the committee’s investigation takes place in a political environment, not a litigation environment. Although the investigatory process appears legalistic, it always unfolds in a political environment in which the actors have political goals that may or may not have anything to do with your client.

Because most people are familiar with Congressional investigations only through television, they assume that if they are caught up in an investigation they will be summoned to testify before a committee like John Dean or Oliver North, with cameras clicking amid vigorous partisan drama. Although your client may indeed be called to testify in a public hearing — and you should prepare as though your client will be called — it is more likely that constraints of time, the demands of the media, and political pressure and compromise having little to do with your client will result in your client never being called. If your client testifies, remember that in many instances the committee members’ “questions” are not actually designed to elicit information from the witness. Rather, questioning is often more like speech-making designed to maximize camera time on the questioner or to score political points against the opposition.

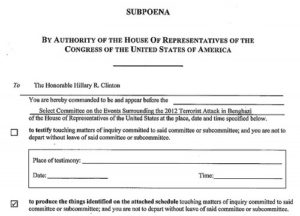

When a congressional committee issues a subpoena, for example, it may (and will) do so with the knowledge and expectation that the recipient may not make even a good-faith attempt at compliance. With regard to recent subpoenas sent to intelligence agencies by the House Intelligence Committee, for example:

Where NSA had previously complied with the House panel’s investigators, sources said that cooperation had ground to a complete halt, and that the other agencies – FBI and CIA – had never substantively cooperated with document requests at all.

Read the story by James Rosen: House Intelligence Committee sends subpoenas to intel agencies

Enforcing subpoena compliance is a legally and politically difficult maneuver for a congressional committee, especially where it seeks enforcement against the executive branch. Customarily, the subpoena issues, then a bit of Kabuki theater ensues, and an agreement is reached, as in the case of General Flynn. Although there are multiple reason why General Flynn . . .

5 Possible Reasons Why Michael Flynn Is Now Turning Over Documents

. . . . may have decided to comply with the document subpoena from the Senate Intelligence Committee, one possible explanation is that his lawyer simply reached an agreement about the scope of responsive documents that was tolerable.

As a necessary aside, I object to the ATL description of the D.C. Circuit’s North opinion as a “three decade old precedent from a split panel [that] rested on a mushy determination that North’s congressional testimony ‘tainted’ the criminal prosecution.” As Judge David Sentelle’s judicial clerk at the time, I reiterate the court’s observation:

The fact that a sizable number of grand jury witnesses, trial witnesses, and their aides apparently immersed themselves in North’s immunized testimony leads us to doubt whether what is in question here is simply “stimulation” of memory by “a bit” of compelled testimony. Whether the government’s use of compelled testimony occurs in the natural course of events or results from an unprecedented aberration is irrelevant to a citizen’s Fifth Amendment right. Kastigar does not prohibit simply “a whole lot of use,” or “excessive use,” or “primary use” of compelled testimony. It prohibits “any use,” direct or indirect. From a prosecutor’s standpoint, an unhappy byproduct of the Fifth Amendment is that Kastigar may very well require a trial within a trial (or a trial before, during, or after the trial) if such a proceeding is necessary for the court to determine whether or not the government has in any fashion used compelled testimony to indict or convict a defendant.

We readily understand how court and counsel might sigh prior to such an undertaking. Such a Kastigar proceeding could consume substantial amounts of time, personnel, and money, only to lead to the conclusion that a defendant–perhaps a guilty defendant–cannot be prosecuted. Yet the very purpose of the Fifth Amendment under these circumstances is to prevent the prosecutor from transmogrifying into the inquisitor, complete with that officer’s most pernicious tool–the power of the state to force a person to incriminate himself. As between the clear constitutional command and the convenience of the government, our duty is to enforce the former and discount the latter.

Read the entire North opinion here.

Congressional subpoenas (such as the one to the right) are not the only examples of tension in legislative investigation. In the impeachment investigation of Alabama Governor Robert Bentley, the issue of legislative authority to enforce subpoenas against the executive branch was front and center, as set out in the Special Counsel’s report:

The Committee Has Subpoena Power.

The Committee has inherent, constitutional authority to issue subpoenas pursuant to its investigative powers. The investigative power of the legislature and, by extension, legislative committees, have been further derived from its broad legislative power. This precedent, though it does not directly discuss legislative subpoenas, clarifies the broad powers enjoyed by the Alabama Legislature while showing great deference to the Legislature’s enactments. Further, an extensive list of other states that have addressed the issue of legislative subpoenas has unanimously endorsed such an ability, with no court finding that its state’s legislature lacks this power.

This Committee has broad power to investigate.

“The Legislature is laden with a broad form of governmental power which is plenary in character, and subject only to those express limitations appearing in the Constitution.”[1] This authority is “absolute or exclusive.”[2] The Legislature’s plenary power is not, as has been suggested by Governor Bentley throughout this investigation, derived from either the State or Federal constitutions; to the contrary, these documents serve as the only limitations upon the Legislature’s power.[3] “Apart from limitations imposed by these fundamental charters of government, the power of the [Alabama] Legislature has no bounds and is as plenary as that of the British Parliament.”[4]

Inherent in the power to legislate is the power to investigate. In McGrain v. Daugherty, the United States Supreme Court held that “[t]he power to legislate carries with it by necessary implication ample authority to obtain information needed in the rightful exercise of that power, and to employ compulsory process for that purpose.”[5] Relying on this precedent, the Alabama Supreme Court also has held that “the power to legislate necessarily presupposes necessity for investigation by members of each House.”[6] This “inquiry power” is sweepingly broad.[7] It encompasses not only the authority to investigate into the propriety of existing and proposed laws but also into the departments of the government “to expose corruption, inefficiency or waste.”[8] Indeed, the United States Supreme Court has recognized that “Congress’s investigative power is at its peak when the subject is alleged waste, fraud, abuse, or maladministration within a government department.”[9] States, too, have recognized that the legislature “is acting at the height of its powers” during an impeachment process.[10] So long as it is “related to, and in furtherance of, a legitimate task” of the legislature, the inquiry falls within the permissible bounds of legislative investigation.[11]

The federal constitution does not give Congress subpoena power, but the United States Supreme Court has repeatedly held that the power to obtain information through compulsion has long been treated as “an attribute of the power to legislate.”[12] “[W]here the legislative body does not itself possess the requisite information—which not infrequently is true—recourse must be had to others who do possess it.”[13] And while “[i]t is unquestionably the duty of all citizens to cooperate with Congress in its efforts to obtain the facts needed for intelligent legislative action,”[14] “[e]xperience has taught that mere requests for such information often are unavailing, and also that information which is volunteered is not always accurate or complete; so some means of compulsion are essential to obtain what is needed.”[15] Thus, a necessary component of the power of investigation is a process to enforce it.[16]

Like the federal courts, the majority of state courts “quite generally have held that the power to legislate carries with it by necessary implication ample authority to obtain information needed in the rightful exercise of that power, and to employ compulsory process for that purpose.”[17] Relying on McGrain and general notions of the plenary authority of the legislature, courts across the country have upheld the constitutionality of legislative subpoenas as inherent in the broad legislative authority afforded to state legislatures.[18]

[1] Ex parte Alabama Senate, 466 So. 2d 914, 917 (Ala. 1985) (quoting Hart v. deGraffenried, 388 So. 2d 1196, 1197 (Ala. 1980)) (emphasis in Ex parte Alabama Senate).

[2] Id. at 918.

[3] In re Opinion of the Justices No. 71, 29 So. 2d 10, 12 (Ala. 1947).

[4] Id. (citing Alabama State Federation of Labor v. McAdory, 18 So.2d 810 (Ala. 1944)).

[5] McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U.S. 135, 165 (1927); see also Mason’s § 795(5) at 562 (the legislature has “the power in proper cases to compel the attendance of witnesses and the production of books and papers by means of legal process”).

[6] See In re Opinion of the Justices No. 71, 29 So. 2d at 13 (citing McGrain, 273 U.S. 135); see also Mason’s § 795(2) at 561 (“The legislature has the power to investigate any subject regarding which it may desire information in connection with the proper discharge of its function . . . to perform any other act delegated to it by the constitution.”).

[7] See Watkins v. United States, 354 U.S. 178, 187 (1957) (“The power of the Congress to conduct investigation is inherent in the legislative process. That power is broad.”).

[8] See id.

[9] Todd Garvey, Congress’s Contempt Power and The Enforcement of Congressional Subpoenas: A Sketch, Congressional Research Service, April 10, 2014, at 3 (citing Watkins, 354 U.S. at 187).

[10] Office of Governor v. Select Comm. of Inquiry, 858 A.2d 709, 738 (Conn. 2004).

[11] See Watkins, 354 U.S. at 187.

[12] McGrain, 273 U.S. at 161; see also, e.g., Eastland v. U.S. Servicemen’s Fund, 421 U.S. 491, 504 (1975).

[13] McGrain, 273 U.S. at 175.

[14] Watkins, 354 U.S. at 187.

[15] McGrain, 273 U.S. at 174.

[16] See id. (“The power of inquiry—with process to enforce it—is an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function.”); Eastland, 421 U.S. at 491 (“[I]ssuance of subpoenas . . . has long been held to be a legitimate use by Congress of its power to investigate.”).

[17] See McGrain, 273 U.S. at 165.

[18] See, e.g., Conn. Indem. Co. v. Superior Court, 3 P. 3d 868 (Cal. 2000); Garner v. Cherberg, 765 P. 2d 1284 (Wash. 1988); In re Shain, 457 A. 2d 828 (N.J. 1982); Commonwealth ex rel. Caraci v. Brandamore, 327 A. 2d 1 (Pa. 1974); Maine Sugar Industries, Inc. v. Maine Industrial Bldg. Authority, 264 A. 2d 1 (Maine 1970); Chesek v. Jones, 959 A. 2d 795 (Md. 2008); Sheridan v. Gardner, 196 N.E. 2d 303 (Mass. 1964); Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Committee, 108 So. 2d 729, 736 (Fla. 1958); State ex rel. Fatzer v. Anderson, 299 P. 2d 1078 (Kan. 1956); Du Bois v. Gibbons, 118 N.E. 2d 295 (Ill. 1954); Nelson v. Wyman, 105 A. 2d 756 (N.H. 1954); In re Joint Legislative Committee, etc., 32 N.E. 2d 769 (N.Y. 1941); Terrell v. King, 14 S.W. 2d 786 (Tex. 1929).

Read the Special Counsel report here.

And, here is your reward for getting all the way through this post: