“Fantastic Lies” and Corporate Criminal Prosecution

Reading Time: 5 minutes.

When the past is dug up in documentaries (or docudramas), events are often sensationalized. This practice is of long pedigree: Shakespeare was not above amping up an old story when it suited his needs. Unfortunately, few filmmakers are at Shakespeare’s level, and the sensationalism ends up being no more than that. The viewer has no better sense of the past than he did when he began. The only sense the viewer has is the sense that she has been had.

On the other hand, from time to time a documentary digs up the past but cools down the facts, making them approachable in a way that would have been impossible at the time. The participants have aged or died; passions have cooled; and political or emotional scar tissue has formed.

On the other hand, from time to time a documentary digs up the past but cools down the facts, making them approachable in a way that would have been impossible at the time. The participants have aged or died; passions have cooled; and political or emotional scar tissue has formed.

Such is the latter case with the recently released ESPN “30 for 30” film about the Duke lacrosse case, Fantastic Lies.

— ESPN (@espn) March 14, 2016

In case you have been lost in Donald Trump’s hair for the last dozen years, the Duke lacrosse case involved a group of varsity lacrosse players at Duke who held a party. Two strippers were paid to provide entertainment at the party. One of them, an African-American woman named Crystal Mangum, claimed that she had been sexually assaulted, verbally abused and threatened with racist epithets.

The case ignited a PC firestorm and witch-hunt, a hunt that would have been academic tragicomedy were it not for the local district attorney in Durham, Mike Nifong, who indicted three players. The lacrosse coach was forced to resign, the season was canceled and the national media had a feeding frenzy.

Nifong was ultimately shown to have withheld exculpatory evidence that demonstrated conclusively that Mangum had not been assaulted by any person at the party. He was disbarred, the players exonerated and lacrosse reinstated at Duke.

Zenovich tells the story almost exclusively through the combination of the words of the (relatively few) participants and witnesses who would speak with her, plus contemporaneous footage of court appearances, lacrosse games, social media posts and state bar disciplinary proceedings. It is a narrative presented with skill, calmness and wonder at how such hysteria happens.

I have written about the Duke lacrosse case and white-collar crime problems before: Dear Colleagues All: University Discipline, Sexual Assault and The Department of Education and Title IX, University Discipline, Sexual Assault and Parallel Proceedings and The Old College Try, and The New College Tribunal.

Those observations were largely in the context of the much larger problem wrought by the federal Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (or “OCR”). The OCR interprets (or misinterprets) Title IX to force colleges and universities to hold Star Chamber-like proceedings in matters of campus sexual assault. (Consider this March 10, 2016 letter — Lankford Letter DOE Title IX — from Senator James Lankford (R-OK), Chairman of the Subcommittee on Regulatory Affairs and Federal Management, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs).

Setting aside the significant implications for students and universities, what can we take away as business people from Fantastic Lies? Here are five thoughts to post in the break room:

Real charges can result from actual innocence. Do not assume, because you have not done anything wrong, that you will not be charged with and convicted of a crime. Innocent people are charged with and convicted of crimes every month (and probably every week) across the country. Prosecutors are not clairvoyant, and they are not divine even when they act in good faith. When they act in bad faith (which is rare), or when they are negligent, incompetent or just don’t understand the business events they are looking at (which is much more common), innocent people will get charged with crimes, and juries will sometimes convict them.

Do not assume that “the truth will out.” The Government has overwhelming discretionary power. The proceedings of a grand jury are secret, manifested by the fact that a witness’s lawyer may not even accompany her client into the room. Agents are intimidating, and citizens think they have to speak with him. The disclosure of “Brady” information – that is, exculpatory information — is wholly within the Government’s control. This is precisely the kind of information that Nifong, the prosecutor in the Duke lacrosse case, withheld. (If you have doubts about whether these sorts of things happen with troubling frequency, read Criminal Law 2.0 by federal court of appeals judge Alex Kozinski. It first appeared in the Georgetown Law Journal Annual Review of Criminal Procedure, but do not worry. It is written in clear, plain English).

Fight back, early. The players and parents in Fantastic Lies did not fully understand what was happening until it was too late. Just as a parent or student cannot rely upon bland reassurances from education bureaucrats in crisis, a corporation or executive cannot put too much weight on comforting words and hinted support from agents, regulators or prosecutors. Assume that something bad is happening and do something about it.

Shut up. When one is investigated, the impulse to share one’s innocence is almost overwhelming. Especially in a high-profile investigation, that impulse will rarely be rewarded because your words will be twisted, compressed and taken out of context.

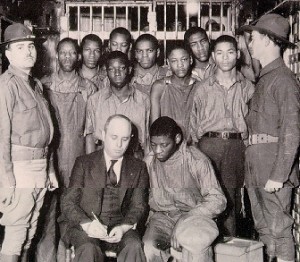

I hope you have money. The defendant students in the Duke lacrosse case did not win simply because they were innocent. They won because their parents were able to afford a team of some of the best criminal defense lawyers in North Carolina. For the purposes of this discussion, the difference between the Duke lacrosse players and the Scottsboro Boys is not race. The difference is cash on hand.

If you are moved by the film, as I was, you may want to look into the work of The Innocence Project, which “was founded in 1992 by Barry C. Scheck and Peter J. Neufeld at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University to assist prisoners who could be proven innocent through DNA testing. To date, more than 300 people in the United States have been exonerated by DNA testing, including 20 who served time on death row.”

A sampling of how the lacrosse community reacted to @30for30’s #FantasticLies on Twitter https://t.co/yyEiGcPlJ4 pic.twitter.com/Q2Yc4W3zfX — Inside Lacrosse (@Inside_Lacrosse) March 14, 2016