Dear Colleagues All: University Discipline, Sexual Assault and The Department of Education

Reading Time: 11 minutes.

Title IX. Crime. Sexual assault. University disciplinary procedures. Civil litigation. Enormous amounts of money. The Fifth Amendment.

And that’s all before you hire a lawyer.

This is a perilous time for university disciplinary systems and those who administer them, especially with regard to claims of sexual assault. A college or university can find itself in the midst of – indeed, at the helm of – a set of quasi-criminal parallel proceedings that can make the school liable to student complainants, student respondents and federal enforcement authorities.

How does this happen, and what are the factors to keep in mind to minimize that exposure?

Disciplinary systems and educational missions have been uncomfortable fellow travelers going back at least to Tom Brown’s Schooldays:

As the concept of in loco parentis came in and out and back into fashion, the nature of university disciplinary systems changed accordingly.

What remained unchanged, however, are the two broad areas that most collegiate disciplinary systems address: “conduct” and “ethics” (or sometimes “honor”). The latter involves cheating, plagiarism and the like. The former involves infractions of nonacademic policies – drinking, destruction of property, and violations of civil or criminal law.

Not surprisingly, most universities have proven themselves more adept at dealing with “academic” infractions then with “conduct” issues. With the advent of coeducation and then a more culturally diverse (and potentially more fractious) student, faculty and staff composition, the proficiency gap between academic-related discipline and conduct-related discipline, in many instances, grew more pronounced.

Back in 2011, the federal Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights issued a “Dear Colleague” letter on the subject of campus sexual assault and how, under Title IX, OCR expects colleges and universities to handle claims of sexual assault. More recently, a White House summit on campus sexual assault; a number of high-profile lawsuits and OCR investigations; and new congressional legislative interest have all conspired to mean that colleges and universities ignore the “Dear Colleague” situation to their peril.

So, my Lightfoot law partner William King (who runs our NCAA practice); summer associate Caitlin Looney; and I (the white-collar guy) prepared a memo. (Truthfully, Caitlin wrote it. All we did was read it and change the date):

On Wednesday, July 30, 2014, a bipartisan group of eight senators introduced legislation aimed at curbing on-campus rape. “The Campus Safety and Accountability Act” would require colleges to assign campus “Confidential Advisors” to act as a resource to victims of sexual assault. The Act would also require a uniform process for disciplinary proceedings and require colleges to coordinate investigations with law enforcement. Penalties for noncompliance could include up to 1% of their total operating budget and a $150,000 fine per violation. The Act would also include annual surveys of students, the results of which would be posted online for the benefit of parents and prospective students. The proposed Act represents the latest development in a flurry of governmental involvement in recent years on issue of sexual assault in schools.

Here is the entire paper: University Disciplinary Procedures and the Dear Colleague Letter on Sexual Assault.

The Campus Safety and Accountability Act, the bill proposed in the Senate, relies in part on a Scarlet Letter approach driven by disclosure of sexual assault (as self-reported by students, rather than administrators or law enforcement), and hefty fines for non-disclosure. As reported by the New York Times:

Every college would be required to participate in the survey and publish results online, and the penalty for colleges that don’t report sexual assault crimes, as required by the Clery Act, would increase to $150,000 from $35,000 per violation.

The new bill proposes fines of up to 1 percent of a college’s operating budget. If Harvard were found responsible, for example, the university would be on the line for $42 million — a sizable fine, but one that would probably not hurt the university’s students. [Harvard’s trustees might differ, but that is another issue. – Ed.]

Colleges would be required to supply confidential advisers to victims and train counselors. Athletic departments would not be allowed to handle sexual assault complaints. Colleges would need to coordinate a uniform plan with local law enforcement agencies. And the bill would provide federal funding to create and distribute an inexpensive, anonymous annual survey that asks all undergraduate students about experiences with sexual violence. Parents and students would be able to see the data, which may influence their decisions when applying to college.

Whether deserved or not in any particular circumstance, college athletic departments are a particular focus, as noted here.

Unlike the disciplinary process for a cheating scandal, a university’s investigation, adjudication and resolution of a sexual assault case is a classic parallel-proceedings scenario. At any moment there may be simultaneously ongoing (1) an administrative proceeding (run by the university); (2) a criminal investigation (run by external law enforcement, sometimes in concert with internal university security and sometimes not); and (3) potential civil lawsuits by either the accuser or the respondent.

Even in the “normal” scenario, parallel proceedings raise thorny issues. In the university disciplinary context, however, they raise at least two special issues, issues often troubling and sometimes disastrous.

First, there is a fourth parallel overlay – the Department of Education’s OCR – that is not present in the usual parallel proceedings situation. The threatened loss of Title IX funds is a near-nuclear scenario for many institutions. (The closest but still imperfect parallel in the business world would be a federal indictment of a company). A Title IX investigation is unpleasant but survivable. The actual loss of Title IX funding may not be.

Second, the due process and Fifth Amendment implications for the student respondent/defendant are exacerbated in ways that are foreign to customary practice and procedure.

Why is this so?

Put yourself in the chair of a defense lawyer whose new client is a student. A complaint has been launched in the university disciplinary system against your client, alleging rape or other serious sexual assault. Consistent with the “Dear Colleague” letter, the university process unfolds swiftly, and your client will soon be offered an opportunity to “tell his side of the story” to a panel of university administrators and faculty. The local police investigators have requested an interview of your client. You have received an email from a lawyer representing the alleged victim who demands that your client preserve all electronic information on his phone such as photos and texts.

At this stage, the defense lawyer may not know much, but she or he knows two things.

First, the lawyer knows that the client is not talking to anybody until counsel is quite certain of the legal landscape generally and, in particular, the client’s status in the criminal investigation.

Second, the lawyer may try a “real world” fix: for Fifth Amendment reasons, stay the civil proceedings pending resolution of the criminal investigation and potential prosecution. Taking the “Dear Colleague” letter at face value, however, and given the prevailing sentiment in this area, a Title IX-compliant university will not be staying much of anything. Although a very short pause in the disciplinary proceedings – on the order of days – is clearly permissible for law enforcement to conduct basic investigative tasks, the kind of stays we in the external world — months and months — is unlikely. Or, as OCR says:

Police investigations may be useful for fact-gathering; but because the standards for criminal investigations are different, police investigations or reports are not determinative of whether sexual harassment or violence violates Title IX. Conduct may constitute unlawful sexual harassment under Title IX even if the police do not have sufficient evidence of a criminal violation. In addition, a criminal investigation into allegations of sexual violence does not relieve the school of its duty under Title IX to resolve complaints promptly and equitably.

A school should notify a complainant of the right to file a criminal complaint, and should not dissuade a victim from doing so either during or after the school’s internal Title IX investigation. For instance, if a complainant wants to file a police report, the school should not tell the complainant that it is working toward a solution and instruct, or ask, the complainant to wait to file the report.

Schools should not wait for the conclusion of a criminal investigation or criminal proceeding to begin their own Title IX investigation and, if needed, must take immediate steps to protect the student in the educational setting. For example, a school should not delay conducting its own investigation or taking steps to protect the complainant because it wants to see whether the alleged perpetrator will be found guilty of a crime. Any agreement or Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with a local police department must allow the school to meet its Title IX obligation to resolve complaints promptly and equitably. Although a school may need to delay temporarily the fact-finding portion of a Title IX investigation while the police are gathering evidence, once notified that the police department has completed its gathering of evidence (not the ultimate outcome of the investigation or the filing of any charges), the school must promptly resume and complete its fact-finding for the Title IX investigation.

Thus, the respondent/defendant is in a crucible. Does he fight the charge in the university’s disciplinary proceeding, or decline to participate in the proceeding so as to avoid statements that the government could use, fairly or unfairly, in a criminal prosecution?

Each situation is different, but rock breaks scissors, and prison trumps college. The respondent/defendant may sue the university on due process grounds, as a Duke student recently did with success, but that is a temporary solution:

Some students who have been expelled or suspended pursuant to a university policy on sexual assault are suing those schools, claiming their rights to a fair hearing were violated. Schools currently involved in litigation with students under these circumstances include: Vassar College, the University of Michigan, Duke University, Occidental College, Columbia University, Xavier University, Swarthmore College, and Delaware State University, among others. Most of these claims have centered on the argument that the hearing processes under new, more stringent standards are unfair. Some of the accused have claimed that the discipline system is now skewed against them because of their male gender and should likewise be considered a violation of Title IX. The likely success of these lawsuits for the accused remains undetermined, but there has been at least one instance in which a judge intervened to keep a school from expelling a student using its internal procedure.

On May 29, 2014, a judge in North Carolina put the expulsion of a Duke University student on hold. Duke determined the student, Lewis McLeod, had committed a sexual assault and should be expelled before spring finals during his senior year of college.Judge W. Osmond Smith III ruled that McLeod would likely suffer irreparable harm if expelled. His ruling blocked Duke from expelling McLeod pending a final determination on the merits.

OCR is not a party to these lawsuits, but the “Dear Colleague” letter makes its position clear, were it required to take one:

Public and state-supported schools must provide due process to the alleged perpetrator. However, schools should ensure that steps taken to accord due process rights to the alleged perpetrator do not restrict or unnecessarily delay the Title IX protections for the complainant.

With regard to due process (and evidence presented in the process), another vexing issue for universities is the question of the appropriate “burden of proof” to apply in campus sexual-assault cases. Historically, most schools seemed to use a standard that was lower than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” requirement that criminal prosecutors must meet but something greater than the “preponderance of the evidence” standard customary in civil lawsuits. It is unclear (at least to me) what the complete constitutional and evidentiary consequences are of making findings that are both civil and criminal using only a civil standard.

It is not unclear to OCR, however:

[I]n order for a school’s grievance procedures to be consistent with Title IX standards, the school must use a preponderance of the evidence standard (i.e., it is more likely than not that sexual harassment or violence occurred). The “clear and convincing” standard (i.e., it is highly probable or reasonably certain that the sexual harassment or violence occurred), currently used by some schools, is a higher standard of proof. Grievance procedures that use this higher standard are inconsistent with the standard of proof established for violations of the civil rights laws, and are thus not equitable under Title IX. Therefore, preponderance of the evidence is the appropriate standard for investigating allegations of sexual harassment or violence.

OCR roots this principle not in Title IX but in the caselaw developed in civil race-discrimination cases under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The statutory foundations of this approach merit further thought, but it is noteworthy that while sexual assault and racial discrimination are both odious and unlawful, only the former is a crime (except for instances of federal deprivation-of-civil-rights situations).

In any event, the shift to the preponderance-of-the-evidence standard is occurring rapidly, as at Harvard:

The new policy, unveiled Wednesday, dramatically changes how cases of sexual assault are handled at Harvard. The new Office of Sexual and Gender Based Dispute Resolution will employ professional investigators and essentially remove investigative responsibility from individual disciplinary boards across schools. Based on the facts provided by the central office, those disciplinary boards will work with University Title IX Officer Mia Karvonides to issue sanctions.

The “preponderance of the evidence” standard that the office will employ is seen by many as a lower burden of proof than the “sufficiently persuaded” standard currently used by the College’s Administrative Board. The preponderance of the evidence standard, favored by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, is generally understood to require more than 50 percent certainty to determine guilt.

Absent from the new policy is an affirmative consent requirement, under which partners must affirmatively communicate their willingness to participate in sexual activity. Activists on Harvard’s campus, such as those involved with the group Our Harvard Can Do Better, and across the country have lobbied for such a clause.

(The Crimson article attaches a copy of the new Harvard policy).

So, what are the takeaways for university administrators and others charged with development an oversight of university disciplinary systems, especially with regard to claims of sexual assault?

Bulk up on the skill. You cannot delegate away “Dear Colleague” responsibility; nor can you simply add it as another part of the job description in Legal or Compliance; nor can you have your “Dear Colleague” program run by someone who is not sensitive to the legal, administrative and — bluntly — political issues that swirl around this effort.

Cut down on the windowdressing. Some companies have magnificent paper compliance programs and codes of business ethics, policies that set lofty standards which, if not undergirded by the actual work, only make the situation worse in the midst of a compliance failure or white-collar criminal investigation. (This is the “don’t write a check your body can’t cash” problem). The university setting is no different. Plus, colleges are thick with committees, panels, town halls, manifestos and missions. Don’t write a policy without thinking through the process, and how defensible it is. And do not confuse compliance with ethics.

Focus on high-visibility groups. Athletic teams and fraternities, fairly or unfairly, bear the brunt of criticism for undesirable campus conduct. On the other hand, those groups are important to university life; have strong alumni support; are in many cases revenue generators (in the case of the athletic department, at least); and can be on–campus bellwethers. Whatever your policy direction and compliance program, if you have these constituencies with you, the job will be much easier.

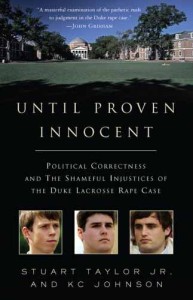

Don’t Nifong respondents. We mentioned the Duke lawsuit above. A prime example of how not to handle university disciplinary procedures was Duke’s process, actions and inactions during the false rape claims lodged against several of its lacrosse players against the backdrop of the misconduct of the now-disbarred criminal prosecutor, Mike Nifong. (We have written about the Duke lacrosse case here. The definitive work on the case remains Taylor and Johnson’s Until Proven Innocent).

A university’s best defense in the “Dear Colleague” era is a combination of sound preparation; an honest approach in plain English; and a firm devotion to the integrity of process for the benefit of its students without regard to externalities (an unethical and unfit prosecutor, for example) or internal pressures (such as small groups of virulent ideologues).