Search Warrants and Filter Teams

Reading Time: 8 minutes.

Here is an article, written with my Lightfoot colleague Mary Parrish McCracken, that originally appeared in a slightly different form in Law360:

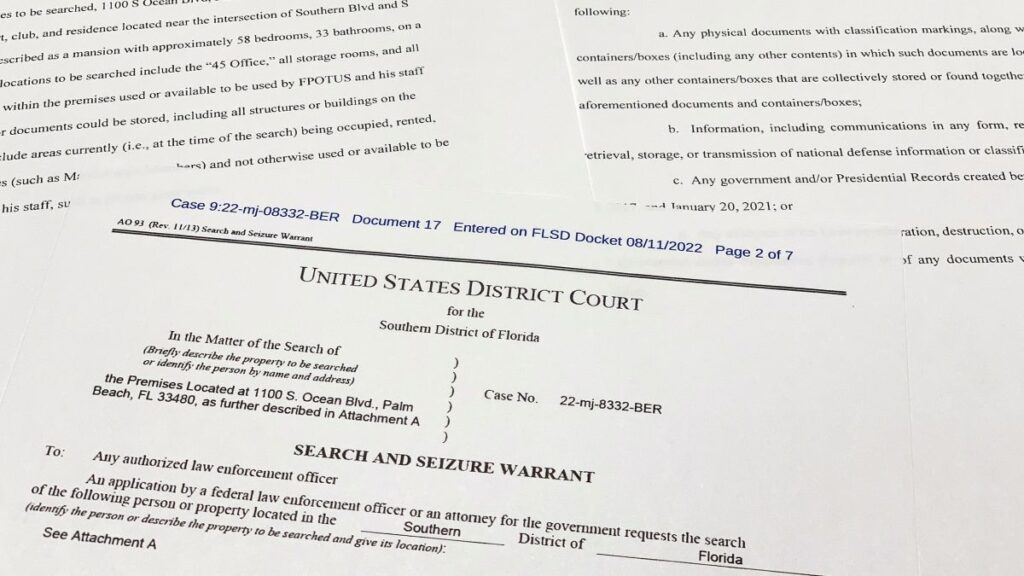

The execution of a search warrant at Mar-a-Lago, the Palm Beach home of former President Trump, brings into renewed focus two aspects of search-warrant practice that are sometimes neglected: the theory and reality of government “filter teams,” and the availability of a neutral special master to review for privilege of the fruits of the search. This article outlines the inherent problems with filter teams, touches upon recent leading cases and concludes with a note on special masters.[i]

When a search warrant is executed on a business or the home of a businessperson, the subject of the search may claim that the agents seized materials protected from disclosure by the attorney client privilege, attorney work-product doctrine or by other applicable privileges.[ii] The Department of Justice’s “Justice Manual” provides for “filter teams.” A “filter team,” which is sometimes called a “taint team,” is a set of federal prosecutors and agents who are not working on, or otherwise have a connection to, the matter under investigation. The filter-team members “remain isolated from the prosecution team(s) and are cautioned not to disclose information discovered during the filter process to the prosecution teams assigned to this, and the related criminal cases.”[iii]

The filter team reviews the materials over which privilege is claimed and makes a determination — usually discretionary — about privilege. It provides non-privileged materials to prosecutors and investigators, and withholds privileged or potentially-privileged items.[iv]

That is the policy. In practice, there are three significant problems.

First, the fox guards the henhouse. The filter team is on the same side as the prosecution team. They may be literally next door to each other, work on similar matters together and in frequent if not constant contact. Even if the filter team acts in good faith, the chances of inadvertent disclosure to the prosecution team are significant.[v]

Second, prosecutors are not known for a heightened sensitivity to protection of privilege. Although privilege enhances truth-seeking by encouraging clients to be candid with their lawyers, privilege is in derogation of truth-finding. Privilege makes the investigation and prosecution harder, not easier.

Third, the privilege determination by the filter team is usually made within its discretion. The defense team does not participate.[vi]

Despite historical judicial deference to the government, filter teams now sometimes face closer scrutiny than previously.[vii] In In re Search Warrant Issued June 13, 2019, 942 F.3d 159 (4th Cir. 2019) (“Baltimore Law Firm”), the court granted a warrant application and ex parte approved a filter team. The Fourth Circuit criticized filter teams on non-delegation grounds, bias and the appearance of unfairness.

The Fourth Circuit noted that the magistrate judge had “erred in assigning judicial functions to the executive branch” by assembling a filter team.[viii] “[W]hen a dispute arises as to whether a lawyer’s communications or a lawyer’s documents are protected by the attorney-client privilege or work-product doctrine, the resolution of that dispute is a judicial function.”[ix] Delegation is especially inappropriate “when the executive branch [the Department of Justice] is an interested party in the pending dispute.”[x] The court acknowledged, refreshingly, that a filter team “might have a more restrictive view of privilege than the subject of the search, given their prosecutorial interests in pursuing the underlying investigations” and emphasized the appearance of unfairness created by filter teams.[xi]

Whereas Baltimore Law Firm was critical of the delegation of judicial function to the executive branch, the Fifth Circuit in Harbor Healthcare criticized the filter team for mishandling privileged information.[xii] A filter team reviewed the seized materials, after which the DOJ declined to meet with the owner or return privileged materials. The Fifth Circuit ordered the return of the seized materials and described the government’s continued retention of privileged documents as a “callous disregard” of the owner’s privilege.[xiii]

On the other hand, the Eleventh Circuit in Korf endorsed filter teams but only where the protocol limited the scope of the filter team’s discretion.[xiv] The protocol provided that, if the filter team determined that a document was not privileged, the team was required to obtain a court order before providing it to the prosecution team. The Korf court found this protocol sufficient because it gave the privilege holder a right to object to disclosure.[xv] More recently, a court in the Northern District of Georgia modified a filter-team protocol to allow the privilege holder to object to disclosure.[xvi]

DOJ created a filter team to inspect the documents collected during the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago, a filter team with broad discretion—it may apply ex parte for a privilege determination, or continue to keep the documents segregated, or disclose the documents to the “potential privilege holder,” who would produce a privilege log and would seek a determination from the court. The last option—disclosure followed by a court ruling—is consistent with Korf, a decision binding on the Southern District of Florida.[xvii] Despite the remedy provided by Korf, the unprecedented nature of a search of a former president’s home, and the intense media attention, the DOJ opposed the appointment of a special master and has informed the court that “the investigative team has already reviewed all of the seized materials that were not segregated by the filter team.”[xviii]

The court rejected the government’s arguments and granted, in part, former President Trump’s request to appoint a special master.[xix] Citing “the need to ensure at least the appearance of fairness and integrity under the extraordinary circumstances presented,” the court will allow a special master “to review the seized property for personal items and documents and potentially privileged material subject to claims of attorney client and/or executive privilege,” and also temporarily enjoined the government from using the seized materials “for investigative purposes pending completion of the special master’s review or further Court order.”[xx]

A special master could address the problems we discuss above and are often used in civil litigation. In the criminal context, however, few courts have ordered that a neutral reviewer be employed. Too often, courts defer to the government and simply take its word that it will do an even-handed, thorough job, much as courts overly defer to the government’s representations that it will discharge its Brady obligations.

A search warrant executed on the home of a former president is, obviously, unique. Donald Trump received his third-party reviewer. This is not the normal course of events we see in non-presidential white-collar practice, but it is a welcome change.

Jack Sharman is chair of the White-Collar Criminal Defense and Corporate Investigations practice group at Lightfoot, Franklin & White LLC. Mary Parrish McCracken is an associate with Lightfoot.

[i] The property on which former President Trump’s home in Palm Beach sits apparently extends from the Atlantic Ocean to the Intracoastal Waterway. Thus, its name (“sea-to-lake.”). Motion for Judicial Oversight and Additional Relief, Trump v. United States, Case No. 22-cv-81294-AMC (S.D.Fla. August 22, 2022) [Doc. 1] (“Trump Motion”) at 4.

[ii] The primary filter-team language is found at Justice Manual 9-13.420 (“Searches of Premises of Subject Attorneys”). Although the heading refers to lawyers’ offices or homes, practitioners generally construe the provisions as applying to the seizure of privilege material wherever it may be found. See also Justice Manual 9-13.410 (“Guidelines for Issuing Subpoenas to Attorneys for Information Relating to the Representation of Clients”) (noting “the potential effects upon an attorney-client relationship that may result from the issuance of a subpoena to an attorney for information relating to the attorney’s representation of a client . . . .”); id. 9‐13.400(D)(7) (“Obtaining Information From, or Records of, Members of the News Media; and Questioning, Arresting, or Charging Members of the News Media”) (“In executing a warrant authorized by the Attorney General or by a Deputy Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division, investigators should use protocols designed to minimize intrusion into potentially protected materials or newsgathering activities unrelated to the investigation, including but not limited to keyword searches (for electronic searches) and filter teams. 28 C.F.R. 50.10(d)(7). Members of the Department should include proposed search and review protocols in their requests for authorization.”) In the Mar-a-Lago search litigation, the government seems to argue that filter teams in general, and the above-cited Justice Manual provisions in particular, are pertinent only to searches of lawyers’ offices. See United States Response to Motion for Judicial Relief and Additional Oversight, Trump v. United States, Case No. 22-cv-81294-AMC (S.D.Fla. August 30, 2022) [Doc. 48] at 30-32 & n.17 (“[S]earches of attorney offices are uniquely fraught and may require different procedures than the searches of-non-attorney premises such as this one.”).

[iii] United States v. Fluitt, No. CR 3:20-00196-01, 2022 WL 1633627, at *1 (W.D. La. Mar. 4, 2022), aff’d, No. 3:20-CR-00196-01, 2022 WL 1625170 (W.D. La. May 23, 2022).

[iv] See, e.g., In re Search Warrants, No. 1:21-CV-04968-SDG, 2021 WL 5917983, at *1 (N.D. Ga. Dec. 15, 2021).

[v] See generally In re: Grand Jury Subpoenas, 454 F.3d 511 (6th Cir. 2006).

[vi] The filter team set up for the Mar-a-Lago search review has broad discretion. See Affidavit In Support of An Application Under Rule 41 For A Warrant to Search and Seize, In The Matter of the Search of Locations Within the Premises to Be Searched in Attachment A, Case 9:22-mj-08332 BER (August 26, 2022) (originally sworn August 5, 2022) at Paragraph 84 (allowing the filter team the option of applying ex parte for a privilege determination, or continuing to keep the documents segregated, or disclosing the documents to the “potential privilege holder,” who would produce a privilege log and would seek a determination from the court).

[vii] See, e.g., United States v. Esformes, 2018 WL 5919517, *20-24 (S.D. Fla. 2018) (raising significant concerns about taint team procedures used). The dispute over the Mar-A-Lago search warrant is in the Southern District of Florida.

[viii] Id.

[ix] Baltimore Law Firm, 942 F.3d at 176.

[x] Id.

[xi] Id. at 177. See also United States v. Neill, 952 F. Supp. 834, 841 n.14 (D.D.C. 1997) (emphasizing that use of filter team creates “appearance of unfairness”).

[xii] Harbor Healthcare Sys., L.P. v. United States, 5 F.4th 593 (5th Cir. 2021) (“Harbor Healthcare”).

[xiii] Id. at 599. Cf. Heebe v. United States, 2012 WL 3065445, *5 (E.D. La. 2012) (another Fifth Circuit case requiring the Government to maintain a record of all Government attorneys or agents who have had access to the privileged records).

[xiv] In re Sealed Search Warrant & Application for a Warrant by Tel. or Other Reliable Elec. Means, 11 F.4th 1235, 1240 (11th Cir. 2021).

[xv] Other courts have similarly found the privilege was not violated where there was independent review by DOJ attorney and a special master, United States v. Smith, 2014 WL 4384026, *2 (E.D. Wash. 2014), and where protocol required maintenance of a record of all DOJ attorneys who had access to privileged records, Heebe v. U.S., 2012 WL 3065445, *5 (E.D. La. 2012).

[xvi] In re Search Warrants, No. 1:21-CV-04968-SDG, 2021 WL 5917983, at *4-6 (N.D. Ga. Dec. 15, 2021).

[xvii] In The Matter of the Search of Locations Within the Premises to Be Searched in Attachment A, Case 9:22-mj-08332 BER, ¶ 84 (August 26, 2022) (Doc. 102-1 originally sworn August 5, 2022).

[xviii] United States Response to Motion for Judicial Relief and Additional Oversight, Trump v. United States, Case No. 22-cv-81294-AMC (S.D.Fla. August 30, 2022) [Doc. 48] at 30. With regard to the potential appointment of a special master, the government argues that an “appointment of a special master would impede the government’s ongoing criminal investigation and—if the special master were tasked with reviewing classified documents—would impede the Intelligence Community from conducting its ongoing review of the national security risk that improper storage of these highly sensitive materials may have caused and from identifying measures to rectify or mitigate any damage that improper storage caused.”

[xix] Order on Plaintiff’s Motion for Judicial Oversight and Additional Relief, Trump v. United States, Case No. 22-cv-81294-AMC (S.D.Fla. August 27, 2022) [Doc. 64].

[xx] Id. at 1. The court did not enjoin the government and the intelligence community from conducting a national security and assessment review.