Defense Crazy, Cocktail Onions, Joy Division

Reading Time: 5 minutes.

LAW

Can a corporation plead insanity as a defense to a criminal charge? In light of reports–accurate or not–relating to the upcoming trial of Elizabeth Holmes, founder of Theranos, there’s been a bit of discussion about whether the insanity defense — well-established and well-discussed with regard to individual alleged offenders — has any applicability to corporate crime.

In The Corporate Insanity Defense, University of Iowa College of Law professor Mihailis Diamantis says “yes, more or less”:

Corporate criminal justice rests on the fiction that corporations possess “minds” capable of instantiating culpable mens rea. The retributive and deterrent justifications for punishing criminal corporations are strongest when those minds are well-ordered. That is when misdeeds are most likely to reflect malice, and sanctions are most likely to have their intended preventive benefits. But what if a corporate defendant’s mind is disordered? Organizational psychology and economics have tools to identify normally-functioning organizations that are fully accountable for the harms they cause. These disciplines can also diagnose dysfunctional organizations where the threads of accountability may have frayed and where sanctions would achieve little by way of deterrence. Punishing such corporations undermines the goals of criminal law, leaves victim interests unaddressed, and is unfair to corporate stakeholders.

This Article argues that some corporate criminal defendants are entitled to raise the insanity defense. Recognizing the corporate insanity defense better serve victims’ and stakeholders’ interests in condemning and preventing corporate misconduct. Statutory text makes the insanity defense available to all qualifying “defendants.” When a corporate criminal defendant’s “mind” is sufficiently disordered, basic criminal law purposes also support the defense. Corporate crime in such cases may trace to dysfunctional systems or subversive third-parties rather than to corporate malice. For example, individual corporate employees may thwart well-meaning corporate policies to pursue personal advantage at the expense of the corporation itself. In such cases, corporations may seem more like victims of their own misconduct rather than perpetrators of it.

In this interview with Professor Diamantis at the Corporate Crime Reporter, he admits that businesses might be incentivized to avail themselves of such a defense only in the most extreme circumstances:

While an initial concern about the corporate insanity defense could be that it would prove too much of a boon for corporations, the opposite concern now arises: Will corporations find the defense attractive enough to raise it? The benefits of the defense only materialize if corporations can see an overall advantage in it. If acquitted, corporations can avoid the reputational costs of conviction, but being declared ‘criminally insane’ would hardly make for an easy public relations challenge. Adding insult to injury, executives and managers seem to be particularly averse to the sort of oversight that rehabilitative corporate treatment that the insanity defense would necessarily entail. Compulsory reform can be expensive and it infringes the autonomy interests that managers guard so closely.

Rigorous thinking about corporate criminal liability is rare, and the corporate insanity defense has an internal logic. As a practical matter, though, it is difficult to see its practical application outside the context of a company that is heading towards dissolution and abandonment.

While we are on the subject of law professors, note that distinguished Columbia professor John C. (“Jack”) Coffee, Jr. has a new book – Corporate Crime and Punishment: The Crisis of Underenforcment. I have not read it, but I set out below the Amazon blurb:

In the early 2000s, federal enforcement efforts sent white collar criminals at Enron and WorldCom to prison. But since the 2008 financial collapse, this famously hasn’t happened. Corporations have been permitted to enter into deferred prosecution agreements and avoid criminal convictions, in part due to a mistaken assumption that leniency would encourage cooperation and because enforcement agencies don’t have the funding or staff to pursue lengthy prosecutions, says distinguished Columbia Law Professor John C. Coffee. “We are moving from a system of justice for organizational crime that mixed carrots and sticks to one that is all carrots and no sticks,” he says.

He offers a series of bold proposals for ensuring that corporate malfeasance can once again be punished. For example, he describes incentives that could be offered to both corporate executives to turn in their corporations and to corporations to turn in their executives, allowing prosecutors to play them off against each other. Whistleblowers should be offered cash bounties to come forward because, Coffee writes, “it is easier and cheaper to buy information than seek to discover it in adversarial proceedings.” All federal enforcement agencies should be able to hire outside counsel on a contingency fee basis, which would cost the public nothing and provide access to discovery and litigation expertise the agencies don’t have. Through these and other equally controversial ideas, Coffee intends to rebalance the scales of justice.

As a white-collar, compliance, and internal investigations lawyer with tuition due for one child still in college, I am selfishly hard-pressed to disagree with anyone, including someone of Professor Coffey’s stature, who wants to foment more business-crime enforcement. Assuming that the Amazon blurb accurately describes the substance of the work, the negative workplace and cultural implications of the KGB-ish informant system he would set up are significant and would, it seems to me, carry their own set of bad incentives. Further, the private-attorney-general model has enough downsides in the civil context. Those downsides would be magnified in the criminal context, as noted in this law review article.

Cocktails

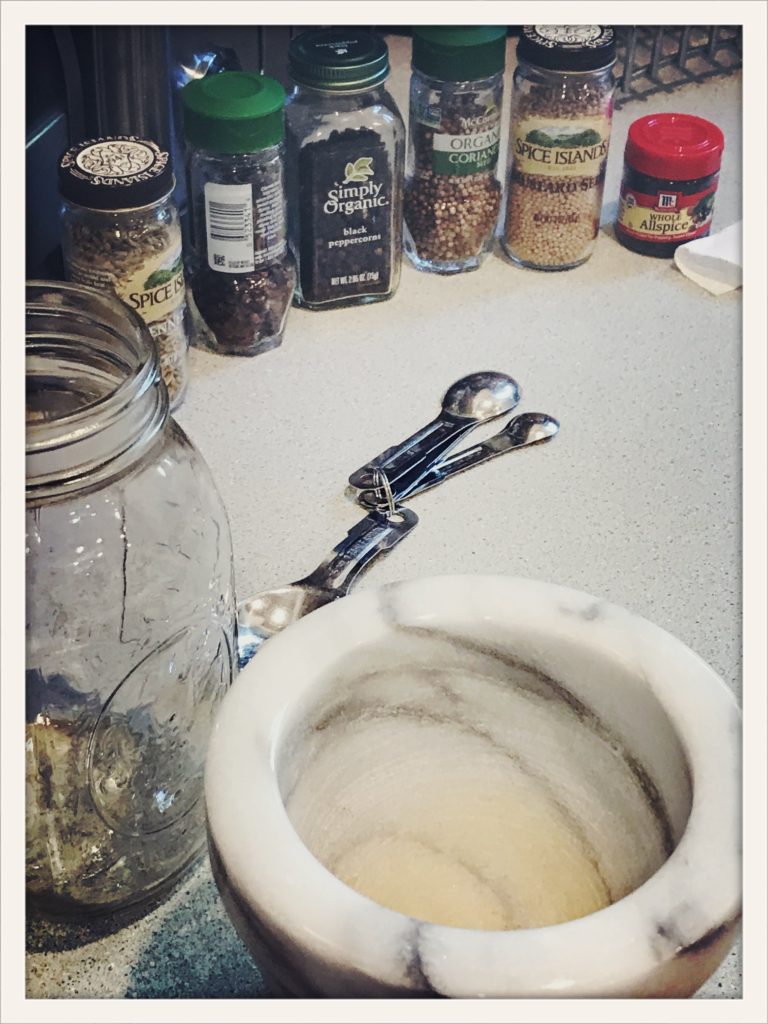

We have written here about the Gibson cocktail. Perhaps the pandemic has worked an undue Maratha Stewart effect, but I decided to make my own cocktail onions. There are multiple recipes, but they all involve vinegars and spices. Here is one by Rosie Schaap.

As you may recall, the Gibson was listed as an official Mad Men cocktail. Cary Grant orders one in North By Northwest (1959) with Eva Marie Saint:

It is too early to be coming up with Christmas gifts, but here is a list of 10 Cocktail and Spirits Books to get you thinking.

Finally, from Liquor.com, a recipe for the Joy Division cocktail and, from Vice, an article to read as you sip it. The group was never my favorite, but it is often mentioned by crime novelist Ian Rankin, and here is a refresher: