Vantage Drilling, General Lee and the Culture of Compliance

Reading Time: 6 minutes.

Gin is a noble spirit; without vermouth, perhaps a lonely one. Similarly, having a compliance program, yet failing to follow it in the presence of some red flags is both lonely and expensive, as we see in the internal accounting controls FCPA case that Vantage Drilling recently settled with the SEC. Is this a problem with culture? And what is “culture,” anyway, in terms of FCPA compliance?

Except perhaps for “paradigm” and “silo,” the word “culture” is one of the most abused in the vocabulary of compliance, ethics and consultants. (I once heard a consultant say that he needed “a high hover over the silos.” I thought it an ironic mash-up about drones and agriculture; it was not). Yet, “culture” has a meaning in the broader world; in commerce; and in compliance. “Culture” represents a gear-shift in compliance and ethics, and can be smooth or bone-rattling.

Consider this story from a few years ago about McKinsey’s culture in the wake of insider-trading scandals:

For a quarter of a century, except for a brief stint as a currency analyst at Rothschild, Mr. Barton has worked at McKinsey, the consulting firm with more than 1,400 partners and 18,500 employees around the world. And that is why he is facing the most daunting task of his career: as McKinsey’s global managing director, he is trying to change the culture of the firm that shaped him.

There are two reasons that Mr. Barton is on this mission: Anil Kumar and Rajat K. Gupta. Mr. Kumar was a McKinsey director who, in 2010, pleaded guilty to insider trading charges and publicly acknowledged giving corporate secrets gleaned on the job to Raj Rajaratnam, a founder of the Galleon Group hedge fund, in return for cash. Never in the history of the firm had a partner been charged with violating securities laws.

A year after the Kumar scandal, the Securities and Exchange Commission filed a civil complaint accusing Mr. Gupta, a Goldman Sachs board member and former McKinsey managing director, of telling Mr. Rajaratnam about a $5 billion investment in Goldman by Warren E. Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway at the height of the financial crisis. Mr. Gupta, a revered former partner who had been elected managing director three times in a row, serving at the helm for a decade, was ultimately convicted of criminal charges of leaking boardroom business. He awaits the outcome of his appeal, even as insider trading charges continue to occupy prosecutors. The trial of Mathew Martoma, a former trader at SAC Capital Advisors, run by Steven A. Cohen, started last week in Manhattan, not long after another SAC trader, Michael S. Steinberg, was convicted of trading on corporate secrets. SAC itself pleaded guilty in November to violating insider trading laws.

So where did that lead Mr. Barton?

At McKinsey, Mr. Barton has been trying to prevent another disgrace: a “third man,” as some have put it. McKinsey is known for what it calls its culture based on values and trust — a culture that was created and nurtured by Marvin Bower, its longtime managing director. The values that Mr. Bower instilled included putting the clients’ interests above the firm’s, providing independent advice and keeping confidences. These ideas were imparted from one generation to the next, mentor to apprentice. But after Mr. Kumar’s arrest in late 2009, Mr. Barton, who had been elected to head the firm just months earlier, decided that the honor-driven, values-based system was not enough. What the firm needed was some rules.

“We needed more safety moats around the castle,” he says. “We have this values/trust culture. I get that. Now we have a little more edge.”

The rest of the article details why some in the firm think this a great idea while others pan it.

On the one hand, for better or for worse, if there is no more “values/trust culture” to be poured in from the top, then the only reasonable thing to do is add “a little more edge.” Like edging your lawn: it seems to grow luxuriantly by itself, but you don’t want grass clogging the sidewalk.

On the other hand, rules — especially rules that are applied to thousands or tens of thousands of employees, perhaps in dozens of countries — are blunt instruments. They hack at the lawn, rather than trim it. In addition, people sometimes revolt against the governing values, but they always revolt against the governing rules. Finally, the rules do a much better job of describing how you transgress than how you non-transgress.

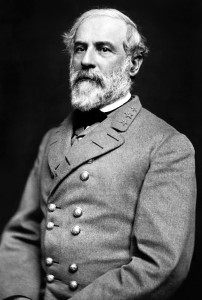

Consider the example of my alma mater, Washington & Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and the Honor System created by President (formerly General) Lee:

The mid-1800s saw the development of honor systems at many colleges. Lee replaced the elaborate disciplinary rules of Washington College by a single standard: “Every student must be a gentleman.” He intended for the young men under his charge to acquire a sense of responsibility based on truth, honor, and courtesy. Lee also placed a premium on civility and spoke to each student as he passed him on campus, encouraging by his example the same show of respect between students.

Today’s honor system, administered by students, has been a unique feature of Washington and Lee University for well over a century. It is based on the fundamental principle of mutual trust among students, faculty, and staff that students attending Washington and Lee will not lie, cheat, steal, or otherwise act dishonorably. With the rule of civility, exemplified by the W&L “speaking tradition,” Lee’s legacy of honor continues to permeate academic and social life at Washington and Lee University and serves as a model nationwide.

An Honor System works well at W&L and poorly at many other universities for several reasons. Some of those reasons illumine the strengths and weaknesses of many corporate compliance programs.

First, as implied above, it is a system, not a code:

Young gentleman, we have no printed rules here. We have but one rule and that is that every student must be a gentleman.

— Robert E. Lee to student Wallace E. Colyar (1866)

Not surprisingly, Lee has come in for reconsideration at W&L, but that reconsideration does not break the link between honor and compliance. Although there are more rules and regulations today in Lexington than there were formerly, the Honor System coalesces around a concept (‘honor”) rather than dividing between thou shalts and thou shalt nots. Despite lip-service to soft concepts in compliance programs, most come down to crypto-Scriptural commands.

Second, the Honor System is single-sanction. There is one penalty — dismissal — without regard to the severity of the offense. In other words, it does not seek proportional justice. Most corporate compliance officers who tried a single-sanction system would get fired.

Third, it marries two starchy concepts: “honor” and “duty.” President Lee cherished the latter as much as the former:

The forbearing use of power does not only form a touchstone, but the manner in which an individual enjoys certain advantages over others is a test of a true gentleman.

The power which the strong have over the weak, the employer over the employed, the educated over the unlettered, the experienced over the confiding, even the clever over the silly–the forbearing or inoffensive use of all this power or authority, or a total abstinence from it when the case admits it, will show the men in a plain light.

The gentleman does not needlessly and unnecessarily remind an offender of a wrong he may have committed against him. He cannot only forgive, he can forget; and he strives for that nobleness of self and mildness of character which impart sufficient strength to let the past be but the past. A true man of honor feels humbled when he cannot help humbling others.

“Duty,” for many employees in highly-diversified, extremely large global organizations is a term roughly co-extensive with “pay.”

Fourth,Washington & Lee is a liberal-arts college with an undergraduate business school and a law school, not the org-chart Tower of Babel that many large-company compliance officers must deal with. Coalescing around a concept (like “honor” or “duty”) rather than submitting to a rule or a checklist is easier when at least a core group is composed of individuals who possess more experiences, taboos, creeds and rituals that unite them than divide them. (Or, at a minimum, they perceive such to be the case).

Corporate compliance programs cannot readily have the grace of the Washington & Lee Honor System — much as (a biased alumnus says) the corporate officer, director or employee without the benefit of a W&L education cannot readily have the grace of a W&L alum. Both require work; both produce imperfection. Both are commendable.