Dante’s Guide: Preparing the Grand Jury Witness

Reading Time: 17 minutes.

(c. 1265–c. 1321)

In the year 1300, at age 35, the narrator of Dante’s Inferno famously finds himself in trouble:

Midway in our life’s journey, I went astray

from the straight road and woke to find myself

alone in a dark wood. How shall I say

what wood that was! I never saw so drear,

so rank, so arduous a wilderness!

Its very memory gives a shape to fear.

The grand jury witness finds himself or herself in a position not unlike that of the Italian poet at the beginning of his trek through the Divine Comedy. The federal grand jury is one of the most powerful, secret and peculiar institutions in American law and culture. It is certainly the most one-sided and the one that most lay persons find runs counter to their civics-class understanding of American governance.

In the poem, Dante has a guide through hell: the Roman poet Virgil. When Dante asks to be saved from the first of three beasts with which he is confronted, Virgil does not spare Dante’s sensibilities:

And he replied, seeing my soul in tears

“He must go by another way who would escape

this wilderness, for that mad beast that fleers

before you there, suffers no man to pass.

She tracks down all, kills all, and knows no glut,

but, feeding, she grows hungrier than she was.”

As lawyers for grand jury witnesses, we must do as Virgil does, and first off remind our client that, like the She-Wolf, the grand jury “tracks down all, kills all, and knows no glut.”

Because the grand jury is distinct from other parts of the apparatus of the American legal system, and because its workings are obscure even to many lawyers, this note first touches briefly on what the grand jury is; where its powers lay; and what restraints there are upon it. In preparing your client for a grand jury appearance – indeed, in advising your client whether or not he or she should even testify before the grand jury – you will need a working knowledge of the institution itself.

After we lay this structural groundwork, we pass on specific thoughts to consider, questions to raise and practices to avoid.

To start with the grand jury, we must start with the Fifth Amendment.

A Prosecution Tool

Under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, “[n]o person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury….” Whether or not your client is to testify about something “infamous,” the Government must proceed by indictment if it intends to charge someone with a federal felony. A defendant has an option of waiving indictment and voluntarily being charged by “information,” a charging document that is issued only by the Assistant United States Attorney (the “AUSA”). Usually, an information is lodged when the defendant has agreed to plead guilty and a guilty plea is being proposed to the court.[1] Historically, and in theory even today, the grand jury is “a protective bulwark standing solidly between the ordinary citizen and an overzealous prosecutor.”[2] Although this observation may have been true at some point in English history, it is not true today. Today, the grand jury is a tool of the prosecution. Decades ago, Sol Wachtler, the former chief judge of New York state, famously observed that a prosecutor could get a grand jury to “indict a ham sandwich.”[3]

Unlike the “12 in a box” of a petit jury, a federal grand jury will have between 16 and 23 members. Sixteen members are required for quorum, and the grand jury can return an indictment only with the agreement of at least 12 grand jurors.[4] If the grand jury does not indict the target or targets that the prosecutor desires (an extremely rare occurrence), it is entirely permissible for the prosecutor to present the same evidence all over again to a different grand jury. In addition, after an indictment has issued, prosecutors may “supersede” (meaning to issue an amended or supplemental indictment on the same subject matter and addressing the same defendant or additional defendants).

The Grand Jury is Secret

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 6 governs grand jury secrecy. Because its secrecy is one of the most powerful characteristics of the grand jury, and one of the most dangerous, the prudent lawyer should review Rule 6 with care.

No Defense Lawyers

The persons who may be present in the grand jury room are quite limited: “Attorneys for the government, the witness under examination, interpreters when needed and, for the purpose of taking the evidence, a stenographer or operator of a recording device….” A lawyer may not accompany his or her witness-client into the grand jury room. Counsel hangs out in the hall or a witness room and waits either for his client to take a break or to be excused when the prosecutors have asked all that they wish to ask. This rule is so strict that a parent may not even accompany a child who is subpoenaed to the grand jury.

Disclosure of Grand Jury Proceedings

Unless certain enumerated exceptions apply, no one involved in the grand jury session except the witness may “disclose… matters occurring before the grand jury.”[5] Unfortunately, the definition of “matters occurring before the grand jury” differs from circuit to circuit. If a disclosure issue arises with your witness, there is no substitute for reviewing the law in your federal circuit. In some circuits, a grand jury witness is entitled to a transcript of his own testimony. In others, he is not.

Can My Client Talk to Others About Her Grand Jury Testimony?

Your client may find his grand jury examination unexceptional or boring, but it is likely to be of great interest to others, especially those who may be subjects or targets of the grand jury investigation or the lawyers for other witnesses who are trying to get their own clients prepared. It is not uncommon for prosecutors and agents to discourage witnesses – sometimes, in strong terms that would get defense counsel charged with obstruction of justice or witness tampering, were defense counsel to do the same – from speaking to anyone about their grand jury testimony and especially from speaking to subjects or targets. Your client should be prepared for those kinds of instructions and should also be prepared to be asked about the identity of anyone they may have talked with concerning their grand jury subpoena or their testimony.

“Can What I Say Get Me in Trouble?”: Grand Jury Subpoenas and Witness Protections

Under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 17, federal grand juries can summon witnesses and require production of documents (and other tangible items). In theory, the grand jury itself issues the subpoenas; in reality, they are issued by the prosecutor. Grand jury subpoenas, unlike trial subpoenas, may be served nationwide: there are geographical limitations within the United States. Failure to respond or appear, at least without a good excuse, is contempt.

The most important protection for a grand jury witness is to not testify. If she doesn’t say anything, nothing she says can be used against her.

The second most important protection for a grand jury witness is the Fifth Amendment.[6] Unfortunately, business people, public officials, professionals and other white-collar types are loath to rely on the Fifth Amendment, concluding – with justification – that most people believe that one who invokes his or her Fifth Amendment rights is guilty of something.

The decision to invoke (or not) one’s Fifth Amendment rights turns on the facts of each case, and a detailed analysis of Fifth Amendment strategy is beyond the scope of this discussion. Nevertheless, a quick review of basic Department of Justice (“DOJ”) policies, as set out in the United States Attorneys’ Manual (“USAM”) is helpful for the witness who has been subpoenaed to the grand jury.

Witness, Subject or Target?

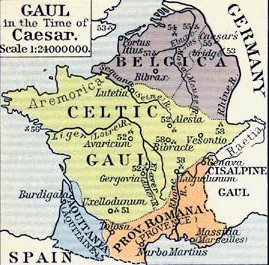

Much as Caesar divided all Gaul into three parts, all grand jury witnesses potentially fall into one of three categories: “witness,” “subject” and “target.”

Of the three categories, the first and the last are the most clear.

A “witness” is akin to the person who was standing at the street corner when the car wreck occurred. They may be asked whether the light was red or yellow, or they may be examined about the speed of the vehicles, but there is no suggestion that they were driving, performed mechanical work on the cars, dashed out in the street to distract a driver or had a financial interest in the death of a passenger. They are, literally, just a witness,

At the other extreme is a “target.” A target is an individual or a company that the Assistant United States Attorney has decided to indict.

A “subject” is everyone else. “Everyone else” is not a very helpful definition, but that is the way the Government looks at it, as we see in the USAM:

It is the policy of the Department of Justice to advise a grand jury witness of his or her rights if such witness is a “target” or “subject” of a grand jury investigation. See the Criminal Resource Manual at 160 for a sample target letter.

A “target” is a person as to whom the prosecutor or the grand jury has substantial evidence linking him or her to the commission of a crime and who, in the judgment of the prosecutor, is a putative defendant. An officer or employee of an organization which is a target is not automatically considered a target even if such officer’s or employee’s conduct contributed to the commission of the crime by the target organization. The same lack of automatic target status holds true for organizations which employ, or employed, an officer or employee who is a target.

A “subject” of an investigation is a person whose conduct is within the scope of the grand jury’s investigation.

The Supreme Court declined to decide whether a grand jury witness must be warned of his or her Fifth Amendment privilege against compulsory self-incrimination before the witness’s grand jury testimony can be used against the witness. See United States v. Washington, 431 U.S. 181, 186 and 190-191 (1977); United States v. Wong, 431 U.S. 174 (1977); United States v. Mandujano, 425 U.S. 564, 582 n. 7. (1976). InMandujano the Court took cognizance of the fact that Federal prosecutors customarily warn “targets” of their Fifth Amendment rights before grand jury questioning begins. Similarly, in Washington, the Court pointed to the fact that Fifth Amendment warnings were administered as negating “any possible compulsion to self-incrimination which might otherwise exist” in the grand jury setting. See Washington, at 188.

Notwithstanding the lack of a clear constitutional imperative, it is the policy of the Department that an “Advice of Rights” form be appended to all grand jury subpoenas to be served on any “target” or “subject” of an investigation. See advice of rights below.

In addition, these “warnings” should be given by the prosecutor on the record before the grand jury and the witness should be asked to affirm that the witness understands them.

Although the Court in Washington, supra, held that “targets” of the grand jury’s investigation are entitled to no special warnings relative to their status as “potential defendant(s),” the Department of Justice continues its longstanding policy to advise witnesses who are known “targets” of the investigation that their conduct is being investigated for possible violation of Federal criminal law. This supplemental advice of status of the witness as a target should be repeated on the record when the target witness is advised of the matters discussed in the preceding paragraphs.

When a district court insists that the notice of rights not be appended to a grand jury subpoena, the advice of rights may be set forth in a separate letter and mailed to or handed to the witness when the subpoena is served.

Advice of Rights

- The grand jury is conducting an investigation of possible violations of Federal criminal laws involving: (State here the general subject matter of inquiry, e.g., conducting an illegal gambling business in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1955).

- You may refuse to answer any question if a truthful answer to the question would tend to incriminate you.

- Anything that you do say may be used against you by the grand jury or in a subsequent legal proceeding.

- If you have retained counsel, the grand jury will permit you a reasonable opportunity to step outside the grand jury room to consult with counsel if you so desire.

Additional Advice to be Given to Targets: If the witness is a target, the above advice should also contain a supplemental warning that the witness’s conduct is being investigated for possible violation of federal criminal law.

USAM 9-11.151.

“If I’m the target, will I be subpoenaed?”

Although it is somewhat rare, a target of a grand jury investigation may be subpoenaed to testify:

A grand jury may properly subpoena a subject or a target of the investigation and question the target about his or her involvement in the crime under investigation. See United States v. Wong, 431 U.S. 174, 179 n. 8 (1977); United States v. Washington, 431 U.S. 181, 190 n. 6 (1977); United States v. Mandujano, 425 U.S. 564, 573-75 and 584 n. 9 (1976); United States v. Dionisio, 410 U.S. 1, 10 n. 8 (1973). However, in the context of particular cases such a subpoena may carry the appearance of unfairness. Because the potential for misunderstanding is great, before a known “target” (as defined in USAM 9-11.151) is subpoenaed to testify before the grand jury about his or her involvement in the crime under investigation, an effort should be made to secure the target’s voluntary appearance. If a voluntary appearance cannot be obtained, the target should be subpoenaed only after the grand jury and the United States Attorney or the responsible Assistant Attorney General have approved the subpoena. In determining whether to approve a subpoena for a “target,” careful attention will be paid to the following considerations:

- The importance to the successful conduct of the grand jury’s investigation of the testimony or other information sought;

- Whether the substance of the testimony or other information sought could be provided by other witnesses; and

-

Whether the questions the prosecutor and the grand jurors intend to ask or the other information sought would be protected by a valid claim of privilege.

USAM 9-11.150.

“This isn’t fair. I want to tell my side of the story.”

Your client may be chomping at the bit to get in the grand jury room and “tell his side of the story.” There are sometimes good reasons to advise your client to not do so but, if he or she insists, note the DOJ policy on the subject:

It is not altogether uncommon for subjects or targets of the grand jury’s investigation, particularly in white-collar cases, to request or demand the opportunity to tell the grand jury their side of the story. While the prosecutor has no legal obligation to permit such witnesses to testify, United States v. Leverage Funding System, Inc., 637 F.2d 645 (9th Cir. 1980), cert. denied, 452 U.S. 961 (1981); United States v. Gardner, 516 F.2d 334 (7th Cir. 1975), cert. denied, 423 U.S. 861 (1976)), a refusal to do so can create the appearance of unfairness. Accordingly, under normal circumstances, where no burden upon the grand jury or delay of its proceedings is involved, reasonable requests by a “subject” or “target” of an investigation, as defined above, to testify personally before the grand jury ordinarily should be given favorable consideration, provided that such witness explicitly waives his or her privilege against self-incrimination, on the record before the grand jury, and is represented by counsel or voluntarily and knowingly appears without counsel and consents to full examination under oath.

Such witnesses may wish to supplement their testimony with the testimony of others. The decision whether to accommodate such requests or to reject them after listening to the testimony of the target or the subject, or to seek statements from the suggested witnesses, is a matter left to the sound discretion of the grand jury. When passing on such requests, it must be kept in mind that the grand jury was never intended to be and is not properly either an adversary proceeding or the arbiter of guilt or innocence. See, e.g., United States v. Calandra, 414 U.S. 338, 343 (1974).

USAM 9-11.152.

“Will I have to take the Fifth over and over again?”

At the other extreme, your client, after discussions with you, may intend to say nothing in the grand jury room except “upon advice of my counsel, I invoke my rights under the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution and respectfully decline to answer your question.” Normally, your client will not have to go to the grand jury and repeat those words for hours, although it can happen:

A question frequently faced by Federal prosecutors is how to respond to an assertion by a prospective grand jury witness that if called to testify the witness will refuse to testify on Fifth Amendment grounds. If a “target” of the investigation and his or her attorney state in a writing, signed by both, that the “target” will refuse to testify on Fifth Amendment grounds, the witness ordinarily should be excused from testifying unless the grand jury and the United States Attorney agree to insist on the appearance. In determining the desirability of insisting on the appearance of such a person, consideration should be given to the factors which justified the subpoena in the first place, i.e., the importance of the testimony or other information sought, its unavailability from other sources, and the applicability of the Fifth Amendment privilege to the likely areas of inquiry.

Some argue that unless the prosecutor is prepared to seek an order pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 6003, the witness should be excused from testifying. However, such a broad rule would be improper and make it too convenient for witnesses to avoid testifying truthfully to their knowledge of relevant facts. Moreover, once compelled to appear, the witness may be willing and able to answer some or all of the grand jury’s questions without incriminating himself or herself.

USAM 9-11.154.

Preparation 101

In some respects, preparing a grand jury witness for his or her testimony is the same as preparing any witness for sworn testimony. Because of the peculiarities of the grand-jury process, however, there are some aspects of preparation that would be odd in other contexts.

Tell the truth. Remind the witness to always tell the truth. Not only is it a good thing to tell the truth, the witness who lies, misleads or obfuscates in the grand jury may face not only a perjury charge but a federal false-statement or obstruction of justice charge. Although it should be obvious, there are no exceptions to these federal criminal statutes for lying to protect children, friends, a spouse or colleagues.

Exercise discipline. Because the witness in the grand jury room is without a lawyer, he or she must exercise unusual discipline. What do we mean by that?

Listen to the question. The witness must listen to the question with even greater clarity and focus than would be required in a deposition, hearing, trial or any proceeding where his or her lawyer were available. There is no counsel present to lodge an objection (speaking or otherwise) or to force the prosecutor to ask a clear question. In addition, unlike a deposition, the witness can be questioned by virtually anyone in the room: prosecutors, an agent and individual grand jurors.

Prepare for multiple examiners. Given the environment in the grand jury room, there is a premium on listening to the question and answering that question directly – and then stopping. Because there is no defense counsel present to sharpen the question, prosecutors can sometimes get lazy, obnoxious or incomprehensible. Grand jurors rarely formulate concise or on-point questions.

Stand your ground. A grand jury witness must also be prepared to stand his ground. A grand jury room can be an odd combination of hostility and lethargy. The confrontational or accusatory tone often found in grand jury examinations is foreign to most witnesses, most of whom have consumed a steady diet of television where prosecutors, agents and police officers are the (very) good guys and the individuals they are pursuing are the (very) bad guys. Your witness needs to be reminded that the reason he has been subpoenaed to testify before the grand jury is because someone in law enforcement believes he has knowledge of a crime (or, at least, of a potential crime). Indeed, simply having mere knowledge of a potential crime is the rosiest situation for a grand jury witness. More commonly, the witness is a “subject” and the Government believes that there is a possibility that the witness may have actually been involved in a federal offense.

Because prosecutors have unfettered sway in the grand jury room, they often exhibit frustration, skepticism or sarcasm when confronted with testimony that is inconsistent with the Government’s theory of the case. This is difficult for the witness inasmuch as he or she frequently has no idea what the Government’s theory actually is. In any event, so as to stick to the straight-and-narrow of truth-telling, the witness needs to be civil but firm in his or her refusal to agree with a statement or assumption that the witness believes is simply not true, however much it irritates the prosecutor.

Hold your testimony close. Your client should be instructed, repeatedly, to not talk with anyone about their grand jury testimony before their appearance and to minimize their discussion of it after their grand jury appearance except with counsel. Both scenarios offer the Government an opportunity to charge witness-tampering as a means to gain leverage over a witness. In white-collar investigations, for example, the Government is likely already convinced that a “conspiracy” of some sort has taken place. It is not a great leap to conclude that conspirators are still running around doing bad things such as trying to influence or change each other’s grand jury testimony.

Look through the Government’s eyes. At this point, you client may protest that he or she is a law-abiding citizen and, if anything, wants to help catch the bad guys. No prosecutor or agent, your client says, would believe that he is a criminal.

Nod, then remind your client that although she may be a law-abiding citizen and possessed of a commendable desire to aid law enforcement, law enforcement does not think like your client. No one involved in the criminal justice system is engaged in a disinterested search for the objective truth. Prosecutors are no exception. They are building a case, assessing it, seeing how strong it is; they do not know your client, and they do not particularly care about him.

This is not a business deal. If your client is a business person, he should be reminded that many prosecutors and agents (although certainly not all) lack extensive experience in the business world. They do not have customers, employees, vendors or patients. They do not have to undergo examination by stock analysts on conference calls or be called on the carpet before the CEO or the board because of a missed sales target or a clumsy merger.

For those reasons, any business activity, whether common or obscure, can to the investigatory eye seem potentially criminal. If the examining prosecutor professes to be shocked, for example, when the witness testifies that a check labeled “commission” was really a commission payment and not an unlawful kickback, he or she should be prepared to stick to his testimonial guns (if the witness in fact truthfully believes that it was a legitimate commission payment).

Do not be afraid to take a break. Remind the witness that she can leave the grand jury room at any time to consult with you wherever you may be stashed, either in the hall or in a witness room. As with witnesses in civil depositions, it is probably better if the witness does not seek to confer with counsel when a question is pending, but the witness’s comfort, security and privilege override everything. Nor does the witness have to say that she wants to consult with counsel. She can simply ask for a break.

Debrief immediately. Debrief your witness as soon as possible after the testimony. Doing so is sometimes difficult because the witness may want to have nothing more to do with a mildly (or greatly) unpleasant couple of hours, or the witness may think that the whole thing was much ado about nothing and not worth even memorializing.

Resist both impulses. Memory starts to fade within minutes after the witness leaves the grand jury room. Except under extraordinary or unhappy circumstances, such as your client’s indictment, you will not get a transcript of what went on in the grand jury room. Your only hope is to get it from the witness’s mouth. How you do so is of course a matter of personal style and preference, although one useful format is to memorialize the testimony in as close to a question- -and-answer format as possible.

Despite the need for speed, do not debrief your witness anywhere near the grand jury room and preferably not in the courthouse. U.S. Attorney’s offices, grand jury waiting rooms and courthouse elevators and corridors are full of eyes and ears, both electronic and human, and it is not worth the risk.

Note in your memorandum the time that your client went in the grand jury room and the time he came out. The length of his examination may be relevant if you are comparing notes with other counsel for other witnesses. Make a note of which prosecutors and agents were in the grand jury room: just because only one came out to retrieve your client does not mean that there were not others in the grand jury room. You should also ask your client if the prosecutor at the outset identified you before the grand jurors as only a witness in the investigation. In that regard, it is good practice for you to ask in advance the AUSA to do so. Many do, but some do not.

In your memorandum, you may wish to expressly state at the beginning that the memorandum is based upon your notes, mental impressions and legal theories arising from and relating to your client’s grand jury testimony and, for that reason, your memorandum should be considered a draft and any conclusions tentative and subject to change. Should the privilege be lost or your memorandum fall into the wrong hands, such language may give your client to distance yourself from any content in the memorandum that turns out to be inaccurate or incomplete but hurtful to your client.

# # # #

In the Divine Comedy, the Roman poet Virgil’s last words to Dante are “lord of yourself I crown and mitre you.” With careful preparation, you will be able to say the same to your grand jury witness.

[1] Fed.R.Crim.P. 7.

[2] United Sates v. Dionisio, 410 U.S. 1, 17 (1973).

[3] Unhappily, Judge Wachtler later pled guilty to extortion and was sentenced to 15 months in federal prison. He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, advocated for the mentally ill and eventually had his law license restored. Novelist Tom Wolfe quotes Judge Wachtler’s “ham sandwich” observation in The Bonfire of The Vanities (1987).

[4] Fed.R.Crim.P. 6.

[5] Fed.R.Crim.P. 6(e)(2).

[6] “No person . . . shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself . . . .”

[NOTE: this post first appeared in American Bar Ass’n, Mastering The Art of Preparing Witnesses (James Miller, ed.) (2017) at 149-160.]