Why We Should Ban Any New “Christmas Carol” and Re-Tune Victorian Hymns

Reading Time: 3 minutes.

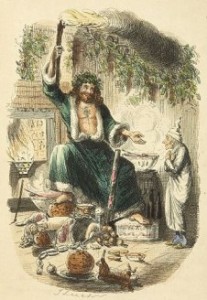

The BBC’s classical music site published this article about the Victorians and Christmas stories. The Charles Dickens classic A Christmas Carol is among them, but so too some more obscure (at least, obscure to me) work by George Eliot and others.

As novelist John Irving noted in an introduction to A Christmas Carol, the work is essentially a Christian ghost story about human transformation:

Scrooge is such a pillar of skepticism, he at first resists believing in Marley’s Ghost. “You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!” Yet Scrooge is converted; beyond the seasonal lessons of Christian charity, A Christmas Carol teaches us that a man—even a man as hard as Ebenezer Scrooge—can change. What is heartening about the change in Scrooge is that he learns to love his fellowman; in the politically correct language of our insipid times, Scrooge learns to be more caring. But, typical of Dickens, Scrooge has undergone a deeper transformation; that he is persuaded to believe in ghosts, for example, means that Scrooge has been miraculously returned to his childhood—and to a child’s powers of imagination and make-believe.

Most of us have seen so many renditions of A Christmas Carol that we imagine we know the story, but how long has it been since we’ve actually read it? Each Christmas, we are assaulted with a new Carol; indeed, we’re fortunate if all we see is the delightful Alastair Sim. One year, we suffer through some treacle6 in a western setting; Scrooge is a grizzled cattle baron, tediously unkind to his cows. Another year, poor Tiny Tim hobbles about in the Bronx or in Brooklyn; old Ebenezer is an unrepentant slum landlord. . . . We should spare ourselves these sentimentalized enactments and reread the original—or read it for the first time, as the case may be.

The Alistair Sim version is a classic, but my favorite is the 1984 version with George C. Scott as Scrooge:

As noted in this Economist book review, the Victorians were also great — perhaps the greatest — hymn-writers, unafflicted by the grinning, emoji-level landscape of most “Contemporary Christian Music”:

[H]ymn-books were the bestsellers of the age. Hymns were a vital part of popular culture: their texts appeared on posters, tombstones and in school reading-books and they were the primary means of teaching the principles of Christianity to adults and children alike. “Let me write the hymns of the church,” one preacher maintained, “and I care not who writes the theology.”

A marvelous contemporary antidote to the milktoast of much CCM is found in the work of Indelible Grace, a movement that “re-tunes” old hymns — many of them Victorian. Here is a look:

The tunes, although all within the same rootsy bandwith, are lovely, and the theology solid.