Thanksgiving Letter: Poetry, Prayer, Cocktail

Reading Time: 6 minutes.

Letter-Writing

Thanksgiving puts one in mind, not surprisingly, of thanks and of thank-yous. Does this concept of giving thanks have something to do with the recent spate of articles and observations about the virtues of writing notes and letters?

In Axios, for example, we read:

Last week, we asked you if you still send and receive handwritten thank-you notes — even though the custom of sending these appears to be dying. Nearly a thousand readers responded — and the answer was resounding across generations: Thank-you notes matter.

Read the story here: Small Note, Big Impact

In the New York Times, we see:

These days, checking your mailbox can be a disheartening experience. You shuffle past catalogs and bills, riffling through political fliers and advertising postcards addressed to “Resident.” But sometimes, if you’re lucky, you come across an envelope with handwriting that you recognize, thanking you for something you did, or gave.

The thank-you note may seem to be an archaic holdover from a time of Rolodexes and rotary phones. But etiquette experts and social observers argue that a handwritten expression of gratitude has never been more important. It can even be a gift itself.

Read the article here (subscription may be required): Do Thank You Notes Still Matter?

There are even studies of the benefits of letter-writing, such as this one.

From a life pockmarked with error, one notable one is that I discovered letter-writing relatively late in life. The pandemic wrought many changes, not the least of which were the confluence of isolation and time. As with gin and vermouth, only two items are required to produce the best traditional products.

Why the current attention to notes and letters, and why should you and I write them?

First, the effect of a letter on the recipient—or at least, on most recipients—ranges from pleased bafflement to head’s-up emotion. Finding a note or letter in the mailbox—an actual piece of paper, folded and placed in an envelope, with a stamp on it—is akin to Cortez gazing upon the Pacific. Much claptrap is written about “being seen,” but letters are perhaps the cure. In our performance culture of digital danse macabre, perhaps the best way to make someone feel “seen,” to verify their existence for them, is to receive a letter from you.

Second, a note or letter influences the writer. I can dictate the first draft of this post, and enter corrections through a keyboard, but neither voice nor tap is as deliberate as moving pen across paper. (Even a typewritten letter, to which I often resort because of my poor penmanship, is a construction project compared to text, snap, or email). To write a letter, one must slow down, pause, restart, and finish.

Third, letters act in unexpected ways and result in unintended consequences, most of them good. The Library of Congress presumably collects tweets, posts, and emails, but such are written on water and lack the stickiness of letters. My mother died when she was 93. In her effects, I found letters that I and others had sent her from decades earlier. When I picked up a postcard from a German museum I posted to her from a backpacking European grand tour in the 1980s, I saw a figure of myself, a young man somewhat recognizable but, in the end, distant as a classmate at a high school reunion. Napoleon supposedly said that to understand a man one must look to the world when he was twenty. Letters have this marvelous retrospective quality that does not suffer from the digital fade of emails or tweets.

Letters are also a remarkable window into the relationship between parent and child. I write letters to my adult children, letters they accept dutifully without fail, at least when I remind them to go to the mailbox. (They respond with greater enthusiasm when funds are enclosed). To get a sense of this dynamic, consider the letters of novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald to his daughter Scottie. Several of them are collected in Fitzgerald’s book in The Crack Up.

All good writing is swimming under water and holding your breath.

F. Scott Fitzgerald to his daughter Scottie (December 1940)

In letters, as in everything else, the relationship between parent and child is both loving and fraught. Here is Fitzgerald’s granddaughter speaking about her grandfather and her mother, Scottie:

Scott was a devoted and difficult father. He was virtually a single parent when my mother [Zelda Fitzgerald] was a teenager. He tried to dictate what she read. He tried to supervise her manners, her interests, and her friends. Scottie wrote, ‘My father had a terrific sense of wasting his own life, his youth, and he was trying to prevent me from squandering my resources as he felt he had squandered his.’ She admitted that at Vassar College she sometimes didn’t open his letters, but was wise enough to stash them in a drawer. ‘Isn’t it odd,’ she continued, ‘that the letters he wrote me, so full of advice and wisdom, but to me, plain harassment, have taken their place alongside his more famous writings?’

Eleanor Lanahan (Fitzgerald’s granddaughter), Forward to The Great Gatsby (Scribner edition 2020)

Note: Maria Popova is an excellent source for epistolary collections.

Thanksgiving Poetry and Prayer

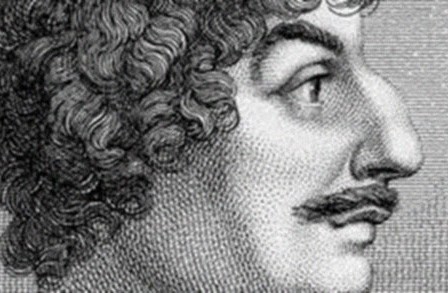

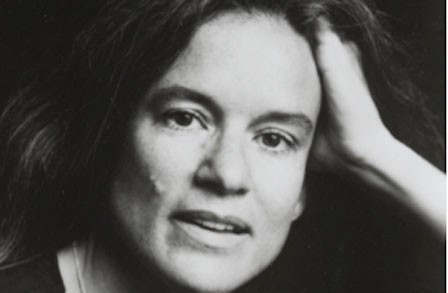

For a pre-meal reading, consider A Thanksgiving to God, for his House by Robert Herrick (1591-1674) and First Thanksgiving by Sharon Olds (b. 1942).

To say grace, one cannot do better than the Book of Common Prayer:

Almighty and gracious Father, we thank thee for the fruits of the earth in their season and for the labors of those who harvest them. Make us, we beseech the, faithful stewards of thy great bounty, for the provision of our necessities and the relief of all who are in need, to the glory of thy Name; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Collect for Thanksgiving Day, Book of Common Prayer (page 194)

Cocktails

As veteran WCW readers know, we favor French 75s before the Thanksgiving meal. From Liquor.com:

Ingredients

1 ounce gin [1.5 ounces of gin is better — ed.]

1/2 ounce lemon juice, freshly squeezed

1/2 ounce simple syrup

3 ounces Champagne

Garnish: lemon twist

Steps

Add the gin, lemon juice and simple syrup to a shaker with ice and shake until well-chilled.

Strain into a Champagne flute.

Top with the Champagne.

Garnish with a lemon twist.

Helen Rosner in the New Yorker is partial to a Boulevardier at Thanksgiving:

For me, on Thanksgiving, that drink is always a Boulevardier. Cocktail historians might blanch at describing it as a variation on a Negroni, but, at least structurally speaking, that’s exactly what it is. You take one part Campari, one part vermouth, and then—and here’s where the magic happens—you forgo the gin, whose piney haze gives a Negroni its crisp and wintry backbone, and instead introduce the warm, spicy roundness of whiskey. You can use any sort, from a plastic-bottle bourbon to a palate-blasting peated Scotch. I’m partial to making it with an intense rye, such as Willett or New Southern Revival.

The Boulevardier is a fine drink. Read the article here: The Perfect Thanksgiving Cocktail Is the Boulevardier.

Happy Thanksgiving.