Taking Five, In Court and Out

Reading Time: 3 minutes.

To take the stand or not?

In the trial of an individual white-collar defendant, perhaps no question is more urgent than this one. To testify (or not) requires a decision on multiple levels, depending on the individual and the facts. But two analyses are always necessary.

First, will the defendant help himself or hurt himself by testifying?

Second, what are the juror-perception implications when the defendant does not justify?

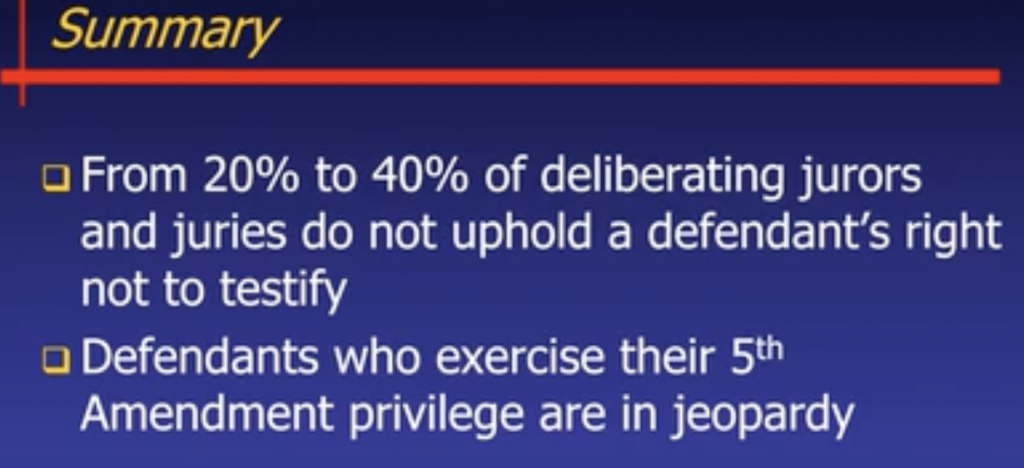

Accomplished jury consultant Kathy Kellermann turned a juror survey into a short slideshow on this topic: Jurors and the Right Not to Testify. Dr. Kellermann’s summary is familiar, unhappily, to many white-collar trial defense counsel:

In an email, Dr. Kellerman noted:

These were deliberating jurors, who were instructed by the judge not to make any inference about the defendant not testifying, and yet they did anyway. Further, 98% to 100% of these deliberating jurors reported that they and their juries strictly followed the law and their jury instructions. Clearly, there is a disconnect that needs to be addressed. I believe this disconnect is best addressed in voir dire, but also needs to be addressed in closing argument.

As usual, it is a matter of de-selection rather than selection—and of both pre-trial preparation and game-time decision making:

The only true protection is to excuse those 20% of jurors who simply do not believe in the right not to testify and are unable not to infer guilt if a defendant does not testify. Let me also say that these data do not imply that a defendant should testify. In these same data, jurors found defendants who testified not to be credible, and their testimony not to be helpful. It is a catch-22.

Nationally-recognized jury consultant Jim Stiff of Trial Strategies emphasized the case-specific trade-offs and the utility of research groups or mock jurors for the particular case:

There may be case-specific reasons that lead some jurors to believe a defendant is “obligated” to testify, particularly if the defendant is the only source of exculpatory evidence. For example, in a recent tax fraud case in which the defendant’s accountant passed away before the criminal indictment, the defendant was the only source of testimony to support a good faith reliance defense. In other cases, the evidence may lead jurors to favor a guilty verdict but leave them with a strong desire to hear from the defendant to eliminate any remaining ambiguity. Jurors seeking greater confidence in their verdict decisions may criticize a defendant for not stepping forward to testify, even when they are predisposed toward a guilty verdict.

There is always a trade-off:

Of course, jurors’ desire to hear directly from the defendant does little to mitigate the obvious risk of subjecting your client to cross-examination. While some jurors may penalize a defendant for not testifying, a decision to testify can shift the burden of proof from the prosecution to the defense, enabling jurors to form judgments about guilt or innocence based on the credibility and demeanor of the defendant, rather than the quality of the prosecution’s evidence.

If the budget allows, run it by different groups:

In preparation for trial, jury research involving a case presentation with and without defendant testimony to different groups of mock jurors will help to uncover juror expectations and the effect of a defendant’s testimony on verdict decisions.

Of course, to “take five” refers to an individual’s invocation of his or her rights, under the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, to not be required to incriminate himself. It is also a Dave Brubeck jazz standard: