Courtrooms & Crime Fiction: Chik-Fil-A, Core Unknowns, and the Presumption of Guilt

Reading Time: 9 minutes.

Narrative fails—in the courtroom or in crime fiction—when the narrator fails to reach into the life of others and thus see what their “real” life is. (For “narrator,” substitute “lawyer” or “writer”). The core life of another— whether they be in a courtroom (as jurors or witnesses) or in a novel (as characters)—can remain unknown. Empathy becomes muddled. Persuasion or entertainment diminished. Ultimately, the case is lost or the story set aside.

If you are a lawyer or a writer, or even just a consumer of what lawyers and writers produce—the justice system, novels—you have a significant interest in this situation. What, if anything, can we do about this problem of the unknown core?

Availability Bias Is Too . . . Available

It’s a bit saccharine, but this video from Chik-Fil-A illustrates the problem of the core unknown:

I am not a psychologist, sociologist, or cognitive scientist. On the other hand, I am sixty years old; I have consumed considerable quantities of gin; and I have spent years trying to discern strangers’ natures and to persuade them of a variety of things (or even entertain them).

One condition that gets in our way when we want to perceive someone’s core, their “real nature,” is what behavioral economists call “availability bias”:

The availability heuristic explains why winning an award makes you more likely to win another award. It explains why we sometimes avoid one thing out of fear and end up doing something else that’s objectively riskier. It explains why governments spend enormous amounts of money mitigating risks we’ve already faced. It explains why the five people closest to you have a big impact on your worldview. It explains why mountains of data indicating something is harmful don’t necessarily convince everyone to avoid it. It explains why it can seem as if everything is going well when the stock market is up. And it explains why bad publicity can still be beneficial in the long run.

We tend to judge the likelihood and significance of things based on how easily they come to mind. The more “available” a piece of information is to us, the more important it seems. The result is that we give greater weight to information we learned recently because a news article you read last night comes to mind easier than a science class you took years ago. It’s too much work to try to comb through every piece of information that might be in our heads.. . .

We also give greater weight to information that is shocking or unusual. Shark attacks and plane crashes strike us more than an accidental drowning or car accidents, so we overestimate their odds.

Farnam Street, The Availability Bias: How to Overcome a Common Cognitive Distortion

You and I tend to think that we are representative of a larger whole. Sometimes we are, but often we are not.

You and I tend to think that we are representative of a larger whole. Sometimes we are, but often we are not:

Personal experience can also make information more salient. If you’ve recently been in a car accident, you may well view car accidents as more common in general than you did before. The base rates haven’t changed; you just have an unpleasant, vivid memory coming to mind whenever you get in a car. We too easily assume that our recollections are representative and true and discount events that are outside of our immediate memory. To give another example, you may be more likely to buy insurance against a natural disaster if you’ve just been impacted by one than you are before it happens.

Thus, our perceptions of others, and our decisions about them, become clouded and inaccurate. When that happens, it becomes difficult to either persuade or to entertain.

We Rush To Decisions

A second hurdle to understanding the “other” (and to making good judgments) is the speed with which we make decisions. Book buyers in physical bookstores may spend only a few seconds to a few minutes before coming to a decision. Jurors start making up their minds within minutes of a lawyer beginning an opening statement:

Adversarial contests create even more urgency for commitment. It is almost impossible to watch any struggle with detached neutrality. We all rush to take sides and then, once we have, to root for the side we are on.

Why? Because we hate to admit that we have made a mistake, and that is what we have to do when we are forced to change positions. And the longer we have had our minds made up, the more difficult it is for anyone to change our minds. Why? Because the longer we have held a position, the bigger our mistake if we must ultimately abandon it. And because our emotions are now involved, not just our reason, we will subliminally work to “mis-hear” and “mis-see,” to the extent we humanly can, to reshape information that does not comport with our previous position—so that we can avoid the admission of error implicit in mind change.

Herbert J. Stern and Stephen A. Saltzburg, Trying Cases to Win (2013)

Unfortunately, when we take our time on a decision, whether about a person or a policy option, we risk looking indecisive. Leaders in contemporary culture strive to at least appear decisive. Many people, and most people reading a blog post like this, want to be leaders.

The Presumption of Guilt Binds Us

The “presumption of innocence” about which we all learned (or, at least, used to learn) in civics class has been translated into a presumption of guilt.

A third reason we usually fail to appreciate another’s real self is that our culture and our judicial system have shifted from being structures based—at least in theory—on a presumption of innocence to structures based on a presumption of guilt. As we noted elsewhere:

The “presumption of innocence” about which we all learned (or, at least, used to learn) in civics class has been translated into a presumption of guilt. Most citizens, most of the time, believe that when a person or company is charged with a criminal offense, they are guilty (or guilty of something pretty close to the charged offense). By the same token, they do not understand why all of the machinery of court – a judge, federal agents, prosecutors, courtroom staff, and they themselves, the jurors – would all be here if there were not a pretty good reason.

White Collar Wire, Public Corruption Trials

The Guilty Pleas of the Innocents

In the Bible, the innocents were slaughtered by Herod for fear of Jesus. In our judicial system, the presumption of guilt, combined with the rise of prosecutors’ plea-bargaining power over over the last century, means that innocent people plead guilty with alarming frequency. It is not fairly characterized as “slaughter,” but it sure leaves a lot of blood on the floor.

In his recent book Why the Innocent Plead Guilty and the Guilty Go Free, Senior United States District Court Judge Jed Rakoff notes:

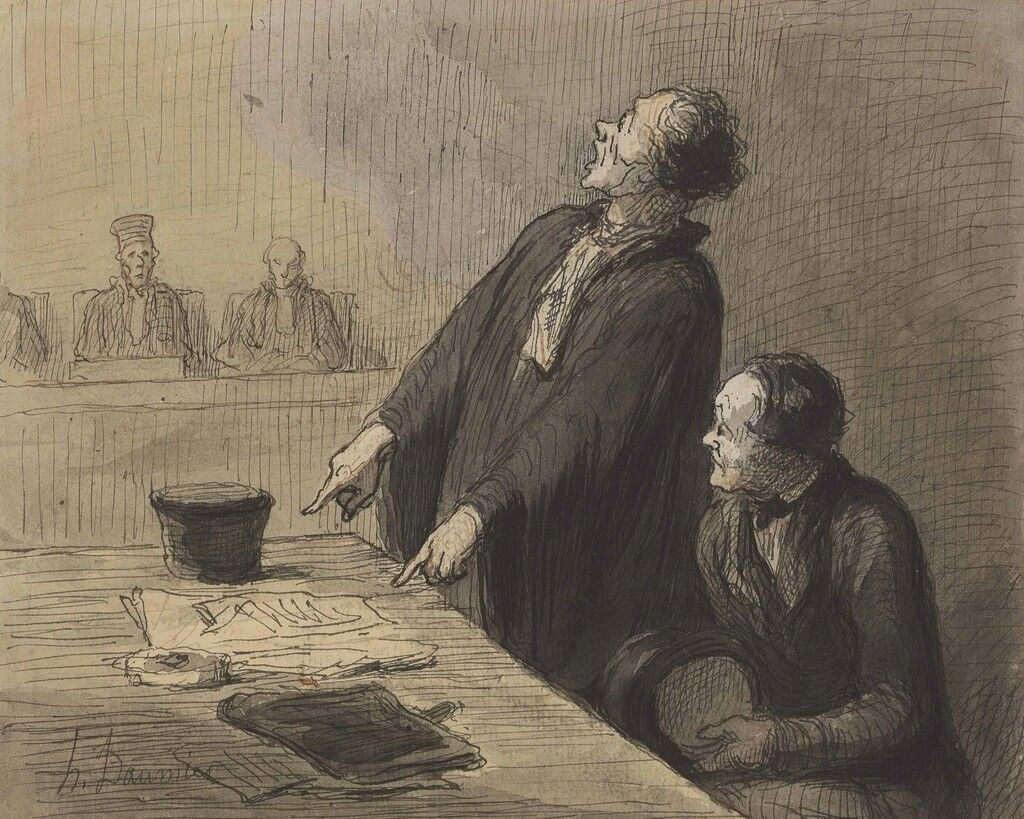

The Sixth Smendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees that “in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury.” The Constitution further guarantees that at the trial, the accused will have the assistance of counsel, who can confront and cross-examine his accusers and present evidence on the accused’s behalf. The accused may be convicted only if an impartial jury of his peers is unanimously out of the view that he is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt and so states, publicly, and its verdict.

The drama inherent in these guarantees is regularly portrayed in movies and television programs as an open battle played out in public before a judge and jury. But this is all a mirage. In actuality, our criminal justice system is almost exclusively a system of plea bargaining, negotiated behind closed doors and with no judicial oversight. The outcome is very largely determined by the prosecutor alone.

. . .

[W]hat really puts the prosecutor in the driver’s seat is the fact that the prosecutor—because of mandatory minimums, sentencing guidelines, and simply his ability to shape whatever charges are brought—can effectively dictate the sentence by how he drafts the indictment.

. . .

Though there are many variations on this theme, they all prove the same basic point: the prosecutor has all the power. The Supreme Court’s suggestion that a plea bargain is a fair and voluntary contractual arrangement between two relatively equal parties is a total myth: it is much more like a “contract of adhesion” in which one party can effectively force its will on the other party.

Jed S. Rakoff, Why the Innocent Plead Guilty and the Guilty Go Free (And Other Paradoxes of Our Broken Legal System) (2021)

As arrested lawyer Mickey Haller says in Michael Connelly’s The Law of Innocence: “Innocence is not a legal term. No one is ever found innocent in a court of law.”

For a similar approach, see former Ninth Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski’s Criminal Law 2.0 . (The fact that Judge Kozinski resigned from the bench under a considerable cloud does not lessen the force of his observations). He points out a set of myths:

- Eyewitnesses are highly reliable.

- Fingerprint evidence is foolproof.

- Other types of forensic evidence are scientifically proven and therefore infallible.

- DNA evidence is infallible.

- Human memories are reliable.

- Confessions are infallible because innocent people never confess.

- Juries follow instructions.

- Prosecutors play fair.

- The prosecution is at a substantial disadvantage because it must prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt.

- Police are objective in their investigations.

- Guilty pleas are conclusive proof of guilt.

- Long sentences deter crime.

Presumptions of Guilt In Your Life

Presumptions of guilt abound outside the criminal justice system. One need only contemplate the dominance of social media in our lives; the pretense and reality of “cancel culture;” and the power of allegations to destroy in the absence of proof—indeed, as in the actual justice system, conviction in the absence of a trial before a jury of one’s peers.

You Want Me to Presume?

One might object that any “presumption”—whether of guilt or of innocence—does not solve the Chik-Fil-A core problem because, as the name implies, it requires that we “presume” (rather than “judge” or “know”) something about someone else. In some circumstances, where the possibility of even a tiny error has potentially catastrophic consequences, such as with nuclear weapons, a presumption of “guilt” may be well-placed as a precautionary principle. In general, however, a presumption of innocence preserves liberty both in terms of individual outcomes and the freedom of a society.

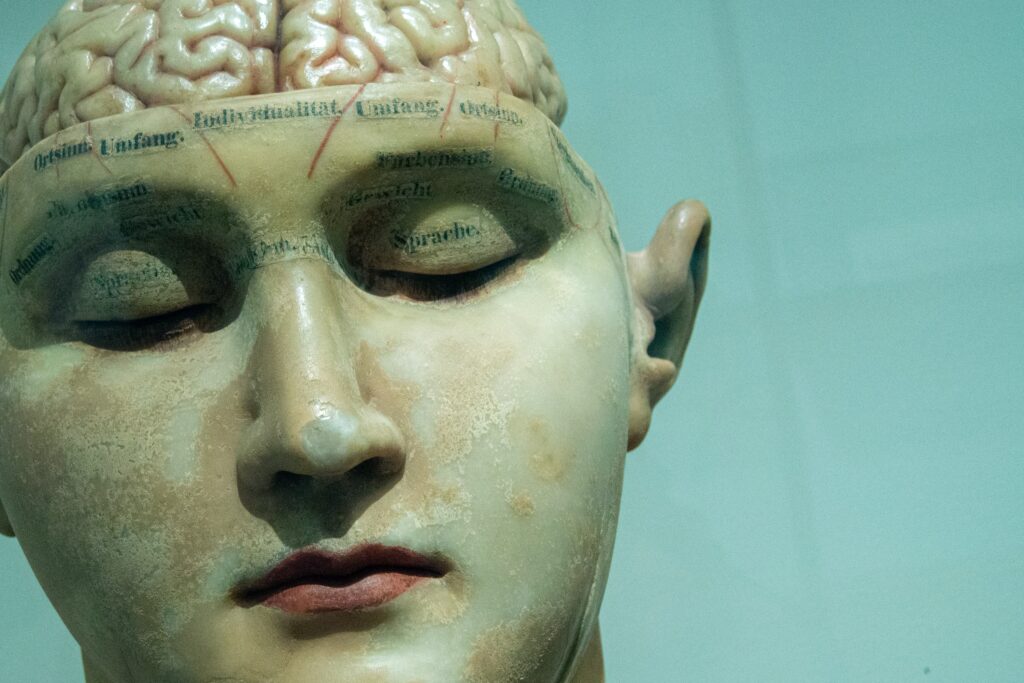

Finally, there is simply too much “noise” in the system. By “noise,“ I don’t mean sound. “Noise“ has two components here.

First, “noise” is all the inputs into your consciousness every moment— other people, your past history, pieces of undigested media, the weather, your health, a memory, the time of day. All of these things are constantly impinge on you and construct your perception of yourself and others.

Second, “noise” is the random scatter of judgments that really should all be the same. There’s no pattern to the pattern.

From the Amazon blurb of Noise by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R. Sunstein:

Imagine that two doctors in the same city give different diagnoses to identical patients—or that two judges in the same courthouse give markedly different sentences to people who have committed the same crime. Suppose that different interviewers at the same firm make different decisions about indistinguishable job applicants—or that when a company is handling customer complaints, the resolution depends on who happens to answer the phone. Now imagine that the same doctor, the same judge, the same interviewer, or the same customer service agent makes different decisions depending on whether it is morning or afternoon, or Monday rather than Wednesday. These are examples of noise: variability in judgments that should be identical.

In Noise, Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R. Sunstein show the detrimental effects of noise in many fields, including medicine, law, economic forecasting, forensic science, bail, child protection, strategy, performance reviews, and personnel selection. Wherever there is judgment, there is noise. Yet, most of the time, individuals and organizations alike are unaware of it. They neglect noise. With a few simple remedies, people can reduce both noise and bias, and so make far better decisions.

Amazon, Summary of Noise.

Remedies Are Only Tactical, Not Strategic

I doubt that the remedies are “simple,” if indeed there exist remedies, but Kahneman and his co-authors make a few helpful points (in my hopefully accurate summary):

- Be humble. Don’t have a high degree of confidence in your judgment, especially when it’s a predictive judgment.

- Trust your gut, but don’t stop there. The intuitive reaction is sometimes right; a lot of times it’s very wrong.

- Seek judgments from other people, then fold them into your own judgment.

- Find at least one comparison case. We tend to make judgments better when we consider a pair rather than a scale.