Roger Stone, the Perp Walk, and Shame’s Role in White-Collar Cases

Reading Time: 3 minutes.

The recent arrest of Trump confidante Roger Stone brings to the fore once again the ‘perp walk,’ an occasion when an arrested defendant is displayed for the media. What is the history of the ‘perp walk’? What is its justification and rationale? Are there limits to it? What – if anything – can lawyers and clients do to protect themselves from running the gauntlet?

These are some thoughts my colleague Bridget Harris and I address in an article in Bloomberg Law.

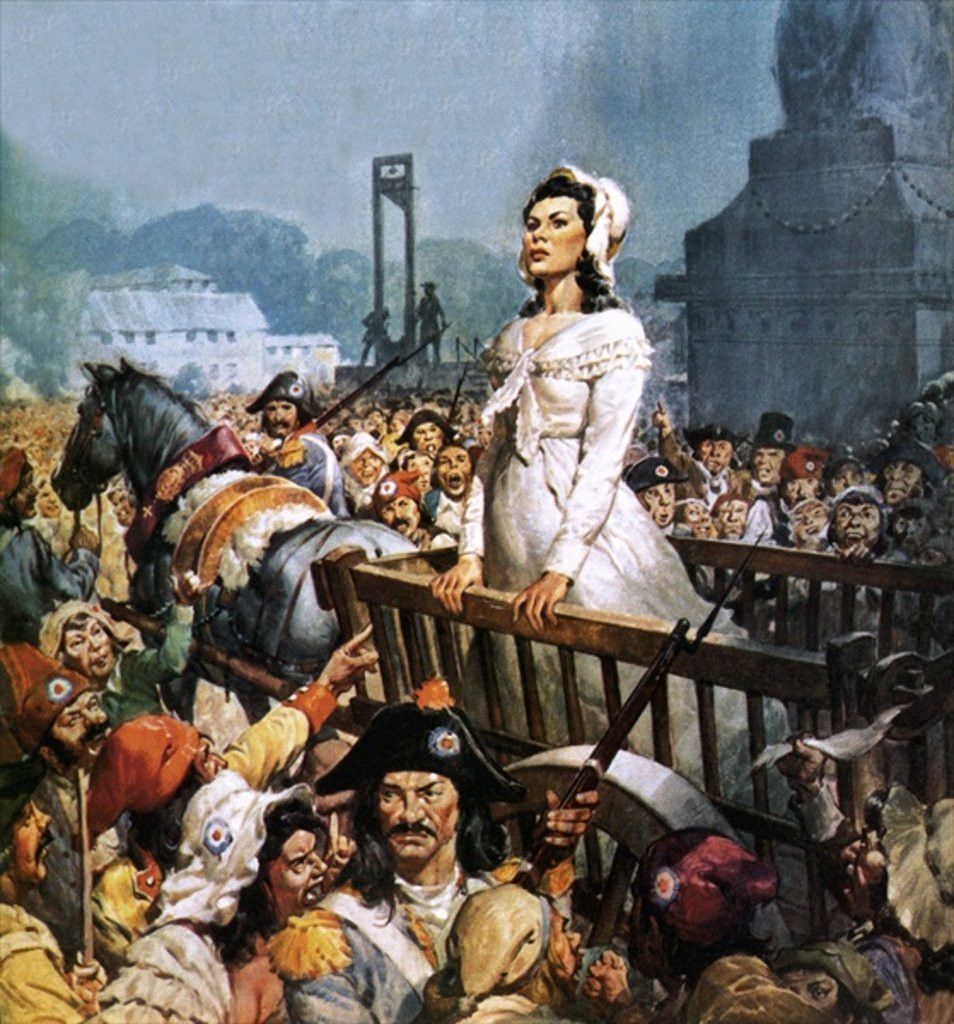

The history of the perp walk is a long one — frequently infamous, sometimes disastrous. During the French Revolution, aristocrats were rolled through mobs on their way to the guillotine. English church reformers in the 16th century were similarly paraded about before being burned at the stake. William Wallace, the 14th-century Scottish rebel, was taken through London’s streets before his execution. As World War II drew to a close, French women whom the community believed collaborated with the occupying Nazis (the “collabos”) had their heads shaved and were mocked in public. President Kennedy’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, was shot dead during a perp walk.

In the United States, the practice has been in place for nearly a century, especially in major metropolitan areas like New York. In the 1930s, the FBI found it useful to publicize its search for and apprehension (or killing) of famous bank robbers. About the same time, film technology had progressed to the point that newspaper-photographers could take high quality photographs while everyone – photographer, handcuffed defendant and law enforcement – was on the move. Current Trump lawyer and former United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York Rudolph Giuliani frequently used perp walks in prosecutions of Wall Street executives. There have been perp walks of mobsters (John Gotti), officials of international organizations (Dominique Strauss-Kahn) and, more recently, media moguls (Harvey Weinstein), actors (Kevin Spacey) and former Trump lawyer Michael Cohen.

The “perp” in “perp walk” is, of course, short for “perpetrator.” A “perpetrator,” the Oxford English Dictionary reminds us, is “one who perpetrates or commits (an evil deed).” The word has been used in this sense since at least 1570, according to the OED, which further points out that “in Latin, the thing perpetrated might be good or bad; but in English the verb, having been first used in the statutes in reference to the committing of crimes, has been associated with evil deeds.”

Much more than a philology lesson, these definitions point us to a foundational curiosity of the perp walk: the individual arrested is a defendant, one charged with the crime. He or she is not a “perpetrator” of anything. No judicial process has determined that he has committed “an evil deed.” Yet, when handcuffed and a bit disheveled, usually because the arrest is in the early morning hours, the defendant certainly looks guilty, an image that can become ingrained in the minds of the jury pool.

When is a perp walk legitimate, and when is it not? And, legitimate or not, is there anything that you as a lawyer can do to avoid it for your client? Read the full article here.