Handwriting On The Wall (And In The FBI’s Notes)

Reading Time: 7 minutes.

As the father of a college-bound high school senior and an eventually college-bound high school sophomore, I pass along to them helpful articles. Whether, in the ancient words of Archbishop Cramner in the Anglican liturgy, they actually “read, learn and inwardly digest” the articles I send them is an open question, but it gives me an uneasy assurance of the discharge of paternal duty.

I passed along to my children a recent Wall Street Journal article that posed the question Can Handwriting Make You Smarter? The article concluded:

Students who took handwritten notes generally outperformed students who typed their notes via computer, researchers at Princeton University and the University of California at Los Angeles found. Compared with those who type their notes, people who write them out in longhand appear to learn better, retain information longer, and more readily grasp new ideas, according to experiments by other researchers who also compared note-taking techniques.

Handwriting is scripturally important, as King Belshazzar finds out in Daniel 5:1-9:

King Belshazzar made a great feast for a thousand of his lords and drank wine in front of the thousand. Belshazzar, when he tasted the wine, commanded that the vessels of gold and of silver that Nebuchadnezzar his father[had taken out of the temple in Jerusalem be brought, that the king and his lords, his wives, and his concubines might drink from them. Then they brought in the golden vessels that had been taken out of the temple, the house of God in Jerusalem, and the king and his lords, his wives, and his concubines drank from them. They drank wine and praised the gods of gold and silver, bronze, iron, wood, and stone.

Immediately the fingers of a human hand appeared and wrote on the plaster of the wall of the king’s palace, opposite the lampstand. And the king saw the hand as it wrote. Then the king’s color changed, and his thoughts alarmed him; his limbs gave way, and his knees knocked together. The king called loudly to bring in the enchanters, the Chaldeans, and the astrologers. The king declared[ to the wise men of Babylon, “Whoever reads this writing, and shows me its interpretation, shall be clothed with purple and have a chain of gold around his neck and shall be the third ruler in the kingdom.” Then all the king’s wise men came in, but they could not read the writing or make known to the king the interpretation. Then King Belshazzar was greatly alarmed, and his color changed, and his lords were perplexed.

Being greatly alarmed, having your color change and seeing your lords perplexed are all often incident to an FBI interview.

Here is another perplexing question: why do FBI agents (and most other federal criminal investigators) not record witness interviews but rather rely on handwritten notes? A layperson could be forgiven for assuming that the agents, unlike the students in the Journal article, are mostly interested in creating a complete, objective record that could be relied upon later. State criminal investigators, in contrast, often do tape-record interviews. (I realize that to say “tape” record is an anachronistic usage. Anachronism is the least of my sins).

FBI agents do not record witness interviews except by handwritten notes, with a recently-added policy exception for custodial interviews (that is, when the witness is in custody and has been given a Miranda warning). Why so?

Here is a useful post by Brian Jacobs of Morvillo Abramowitz Grand Iason & Anello P.C. on the subject: Why Do Federal Agents Still Take Interview Notes by Hand?. In particular, he suggests that agents at least be required to take notes by laptop:

Another explanation for why the standard practice has gone largely unchallenged might be that when a witness interview is memorialized in an agent’s hand-written notes, there will necessarily be ambiguities, and those ambiguities can have benefits for both the government and the witness. For example, to the extent a witness’s story changes between the initial interview and trial it will be more difficult for defense counsel at trial to impeach the witness’s testimony with handwritten notes than with a typed record. This helps both the government as well as the witness him or herself.

. . . .

Of course, if the goal is to have a perfect record of witness interviews, then they should all be recorded and transcribed. That would be a worthwhile goal for the government to pursue. In fact, the government itself has gestured in this direction: Deputy Attorney General Cole’s memo calling for the recording of custodial statements also encouraged “agents and prosecutors to consider electronic recording in investigative or other circumstances” beyond custodial interviews. Until recording and transcription become the norm, however, the government should consider taking interview notes on a laptop computer. This method works for law students; it can work for federal agents.

The goal, of course, is not to have a perfect record.

In FBI witness interviews, there are almost two agents. One is the questioner who focuses on the witness and one is the secretary who takes note. When the witness says something inconsistent with the Government’s theory, or exculpatory of a target (or of the witness, for that matter), it is not uncommon to see the “clerical” agent simply stop writing until the witness gets back on a preferred course. Taking notes by hand allows agents to perform this start-and-stop procedure, whereas a recording would capture everything said.

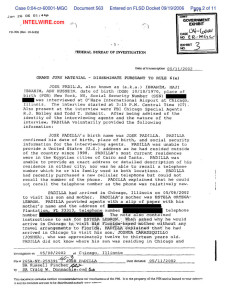

The FBI agent’s notes are turned into “302s,” interview memoranda so nicknamed from their federal-form number.

Although there is little “discovery” in criminal cases as compared to civil lawsuits, the government must frequently disclose “302s” to defendants when those 302s contain Brady material (that is, statements or other information tending to show the innocence of the defendant); Jencks material (statements of Government witnesses); or Giglio material (statements or writings tending to impeach or diminish the credibility of Government witnesses).

The problem is obvious: with each memorialization from notes to memorandum, something is lost in translation, whether intentionally or not. The translation-loss is why the standing criminal-discovery orders in some federal courts require the case agents to maintain their notes and also why it is good practice for defense counsel to demand that the agents preserve (and disclose) their notes, although the latter demand is sometimes a tall order.

Should you receive the underlying notes in discovery, the lost-in-translation problem becomes more pungent — and unfixable — because in the creation of her handwritten notes the agent has complete discretion. When we combine that editorial discretion with the The Efrem Zimbalist, Jr. Syndrome, the interviewee is in an impossible position:

“Government Agents,” a Lightfoot140 by Jack Sharman. from LFW on Vimeo.

This issue has been addressed before by Douglas Starr in The New Yorker (The F.B.I.’s Interrogations, Finally on Film); by Tim Cushing in TechDirt (Your Word Against Ours: How The FBI’s ‘No Electronic Recording’ Policy Rigs The Game… And Destroys Its Credibility ) and by David Drumm (guest blogging for Jonathan Turley) (Why The FBI Doesn’t Record Interrogations). Starr raises a useful point about recording policies and trial effects in federal versus state or tribal trials:

The federal government is, in this respect, far behind the states. Alaska required recording in 1985, followed by Minnesota, in 1994; now twenty states require it, as do the District of Columbia and hundreds of individual precincts. States with big Indian reservations have provided a sort of controlled experiment in the differences between federal agents, who did not record, and local police, who did. On the reservations, tribal officers investigate misdemeanors, while agents from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the F.B.I. investigate major crimes such as murder, rape, and arson. Once charged, the suspect faces indictment in federal court, generally in a major city off the reservation. Paul Charlton, a former U.S. Attorney for Arizona, recalls many trials in which even the most minimally competent defense lawyer would know enough to contrast the behavior of F.B.I. agents with that of the local police. In “long, excruciating cross-examinations,” those lawyers would ask agents if the Bureau owned a recording device; if it was small enough to take to the Navajo reservation; if the device had an On button; if the agents knew how to use the On button … and on and on, until the agents’ refusal to record the interrogation seemed nothing short of ridiculous.

“So we would either lose cases, plea down cases, or find some lesser charge,” Charlton said. He got so tired of the situation that he ordered all federal investigators in Arizona to record interrogations, the rules notwithstanding. That helped to put him on the wrong side of the U.S. Attorney General at the time, Alberto Gonzales, who eventually dismissed him along with eight other U.S. Attorneys in a controversial mass firing in 2006.

An even more useful “lab” for comparison is an investigation conducted by a joint federal/state team. The state agent tape-records Jane Smith’s interview; the federal agent just takes handwritten notes. In discovery, you may then get from the Government the state-agent’s tape and the federal agent’s 302 of the same interview. The discrepancies can be fertile ground for cross-examination and for motions to compel production of the federal agent’s handwritten notes.

In an age of iPhones and voice-over-internet-protocols, is there any longer a meaningful reason for criminal interviews to not be recorded? Witness interviews are often the basis for federal false-statement charges under 18 U.S.C 1001. What is at least part of the evidence that the statements are “false,” according to the Government? Because the agent gets on the stand and says, “Here is what the witness said to me, as reflected in my 302 [or my notes].” If a trial seeks the truth, would we not rather know what the witness said, actually?

If a false statement is about untruth, cannot jurors also handle the truth?