Global Privilege Issues

Reading Time: 15 minutes.

[NOTE: my friend and law school classmate Greg Schuetz co-authored this piece, which appeared in the June issue of “The Docket,” the monthly publication of the Association of Corporate Counsel. Greg is Chief Legal Officer for Messer Americas, an industrial and medical gases company based in Bridgewater, New Jersey. Previously, he was General Counsel-Americas and Head of Global Litigation for The Linde Group, a global gases company, headquartered in Munich, Germany. Before joining Linde, he managed domestic and international automotive product liability for DaimlerChrysler Corporation, litigated civil disputes at Feeney Kellett Wiener & Bush in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and served as an Assistant United States Attorney in Detroit.]

Few doctrines are held so dear by so many American lawyers, yet understood by so few, as the concept of privilege between lawyer and client. Attorney-client privilege is the stuff of law school courses, bar-association CLEs, and universally-ignored footers on emails. It seems, somehow, to be a core value for the practice of law, the kind of guild secret that keeps lawyers in the company of physicians and priests.

Yet other legal systems have a very different view of privilege, or dispense with it altogether. Is the attorney-client privilege one of the pillars of a global right to practice? Or a universal right for clients to have their secrets kept? Whether it is or not, how are in-house counsel with a cross-border practice supposed to think about privilege (or its lack thereof)? In an era in which information is disseminated globally at unprecedented speed, how does company counsel discharge his or her ethical duties; serve the client; and comply with multiple — and sometimes conflicting — practice regimes?

This article first covers the basics of the attorney-client privilege, then moves to a consideration of jurisdictions that see the attorney-client relationship in a different light, using the United Kingdom and Germany as examples. After reviewing the points of convergence and divergence, both in doctrine and in practice, the article concludes with a practical set of questions for in-house counsel to walk through so that he or she is able to advise the client of the benefits and burdens, and the risks and rewards, of any particular cross-border situation.

The attorney-client privilege and attorney work-product doctrine in the United States

In 1981, in the Supreme Court’s seminal Upjohn decision,[i] the Court noted that the purpose of the attorney client privilege is “to encourage full and frank communications between attorneys and their clients, and thereby promote broader public interests in the observance of law and administration of justice.” [ii]That rationale has deep roots in America. In 1888, the Supreme Court declared that the privilege “is founded upon the necessity, in the interest and administration of justice, of the aid of persons having knowledge of the law and skilled in its practice, which assistance can only be safely and readily availed of when free from the consequences of the apprehension of disclosure.”[iii]

The attorney-client privilege gives attorneys and their clients permission to refuse to divulge the contents of their communications which were made in the course of legal representation. For the attorney-client privilege to attach, it must be:

(1) A communication;

(2) Made between privileged persons;

(3) In confidence; and

(4) For the purpose of obtaining or providing legal assistance.

The client holds the privilege, not the lawyer, and the client must explicitly assert it. (In other words, the privilege is not self-executing). Disclosure to a third party usually waives the privilege, although there may be a question as to the scope of the waiver. Finally, the privilege will be lost if the adverse party can demonstrate that the communication furthered a crime or fraud (the “crime-fraud exception”).

In the United States, internal corporate counsel are subject to the same privilege analysis as outside counsel, but in-house counsel usually wear business hats, as well as a legal one. The privilege rarely covers business advice, and disputes arise over the nature of the advice given or communication made. If a communication exhibits both “legal” and “business” aspects, then the analysis follows a “primary purpose” route.

The attorney work-product doctrine is not a privilege. Rather, it is creation of the common law that protects one against against discovery or forced production. The doctrine shields documents created “in anticipation of litigation.” Work-product protection can be overcome by a showing of (1) a “substantial need” of the materials in order to prepare the case for trial and (2) “undue hardship” in obtaining the substantial equivalent of the materials by other means. “Opinion” work product – sometimes called “core” work product — is never discoverable. Like the attorney-client privilege, however, other work-product protection may be lost by waiver. Lawyers, paralegals and staff should handle materials protected by the attorney work-product doctrine with the same care and discretion they use with attorney-client communications.

Different members of the legal community have divergent views of the attorney-client privilege and the attorney work-product doctrine. In general, corporate counsel, clients, and outside defense counsel have an expansive view – often, too expansive — of these doctrines. On the other hand, prosecutors, plaintiffs’ lawyers and many judges have a narrower interpretation of the scope of the privilege or attorney work product protections. In particular, because internal counsel in the contemporary corporation wear multiple hats (and indeed must do so in order to serve the business client), many courts are skeptical that an internal lawyer’s communications mixing business management with legal analysis and advice, should enjoy the privilege at all.

Privilege in the United Kingdom

The current touchstone for privilege is the U.K. Court of Appeal’s decision in September 2018 in Director of the Serious Fraud Office v. Eurasian Natural Resources Corp. Ltd.[iv] In ENRC, the appellate court reversed a lower court’s ruling that had significantly narrowed the attorney-client privilege in internal investigations. The appellate opinion merits a careful review, but a few initial definitions are in order. “United Kingdom” refers to England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. For some legal matters, such as libel, Scotland has its own, separate jurisprudence, but privilege laws are uniform throughout the United Kingdom.

Is there an attorney-client privilege?

Yes, generally speaking.

Three main types of privilege concern us in the United Kingdom: the “legal advice” privilege, the “litigation privilege,” and the “common interest” privilege. The first two types are usually considered together as the “legal professional” privilege.

The “legal advice” privilegeis most closely analogous to the American attorney-client privilege. It protects communications intended to be confidential between lawyer and client. As in the United States, the communication, to be protected, must concern the offering or receiving of legal advice (as opposed to business advice or strategic counsel). The precise identity of the client, may differ from what lawyers outside the UK might consider to be the client, as we explain below.

The “litigation” privilege expands the scope of protection for materials intended to be confidential and whose creation was for the “dominant purpose” of responding to existing or anticipated litigation. There is no attorney-work product doctrine in the UK, but the litigation privilege in some circumstances serves a similar role. More expansive than the “legal advice” privilege, the litigation privilege can shield documents created by lawyers (and even by clients) as well as communications between lawyers and third parties. The privilege’s rationale, to allow lawyers and clients to exchange information and advice freely, echoes the policies articulated in Upjohn. As one might expect, however, a frequent bone of contention is whether the “dominant purpose” requirement is met, especially in the earliest stages of an internal investigation.

Finally, the “common interest privilege,” akin to the “joint defense privilege,” provides that individuals or entities with investigation or litigation interests that align with each other may share privileged material safely without loss of the privilege. As sometimes in the United States, one issue can be whether the parties’ interests are the same (or at least similar enough to qualify for the privilege).

Who is the client?

For purposes of privilege analysis, the definition of the “client” is broader and more flexible in the United States than in the United Kingdom. In Three Rivers No 5,[v] the Court of Appeal held that only a limited group of employees with authority (express or implicit) to seek and receive legal advice on behalf of a company qualified as the “client” for the purpose of legal advice privilege. Communications with employees outside that special group may not benefit from the privilege. This principle is much more restrictive than that described by Upjohn and its progeny in the United States. Such a “control group” type of test affords much less protection to interviews of line employees.[1]

What does ENRC teach us?

In 2010, a whistleblower notified ENRC that certain allegedly fraudulent practices were occurring in the company’s subsidiaries in Kazakhstan and Africa. The audit committee of the parent company engaged law firms to conduct an internal investigation and also to enter into discussions with the Serious Fraud Office (SFO). The company also hired forensic accountants to conduct a books-and-records review with an eye towards, first, assessing the company’s liability under the relevant bribery and anti-corruption laws and, second, to provide advice regarding the company’s compliance program. The lawyers and the accountants engaged in a broad, lengthy investigation, as well as a multi-year discussion with the SFO under the then-existing self-reporting regime established by that agency.

Under section 2 (9) of the Criminal Justice Act of 1987, a person under investigation may refuse to disclose documents on the grounds of legal professional privilege (one of the concepts we discussed above). The SFO eventually opened a formal criminal investigation into the company, which asserted privilege. The SFO claimed that the documents created during the internal investigation did not benefit from the legal professional privilege. The court of original jurisdiction agreed. ENRC appealed. The appellate court reversed the lower court’s ruling on almost all points.

The appellate court’s opinion is lengthy and detailed. It noted that “the whole sub-text of the relationship between ENRC and the SFO was the possibility, if not the likelihood, of prosecution if the self–reporting process did not result in a civil settlement.” E

[paragraph 93]

The court conceded that “we are not sure that every SFO manifestation of concern would properly be regarded as adversarial litigation, but when the SFO specifically makes clear to the company the prospect of its criminal prosecution …, and legal advisors are engaged to deal with that situation, as in the present case, there is a clear ground for contending that criminal prosecution is in reasonable contemplation.”[vi] For that reason, the lower court should have concluded that most of the documents were created “for the dominant purpose of resisting or avoiding those (or some other) proceedings.”[vii]

In addition, the lower court had placed great weight on the fact that the documents that the company’s outside lawyers prepared as a result of the investigation were assembled with the possibility of using them in a presentation to the SFO. The appellate court disagreed, noting that the “fact that solicitors prepare a document with the ultimate intention of showing that document to the opposing party does not, in our judgment, automatically deprive the preparatory legal work that they have undertaken of litigation privilege.”[viii]

The appellate court addressed two other matters of particular importance to corporate clients and their lawyers: (1) who is the client and (2) how privilege works with in-house counsel.

As to the first issue, the court observed – with obvious reluctance – that Three Rivers No. 5 “decided that communications between an employee of a corporation and the corporation’s lawyers could not attract legal advice privilege unless that employee was tasked with seeking and receiving such advice on behalf of the client….”[ix]

The court noted that “large corporations need, as much as small corporations and individuals, to seek and obtain legal advice without fear of intrusion.… In the modern world … we have to cater for legal advice sought by large national corporations and indeed multinational ones. In such cases, the information upon which legal advice is sought is unlikely to be in the hands of the main board or those [the company] appoints to seek and receive legal advice. If a multinational corporation cannot ask its lawyers to obtain the information it needs to advise that corporation from the corporation’s employees with relevant first-hand knowledge under the protection of legal advice privilege, that corporation will be in a less advantageous position than a smaller entity seeking such advice.”[x] The court found that Three Rivers No. 5 was not squarely before it, but urged supreme court review of the rule.

In-house counsel are differently situated than outside counsel

The appellate court also reinforced the notion that, rightly or wrongly, in-house lawyers may not benefit from the same protections as their external counsel. In ENRC, the court considered a series of email exchanges between the company’s head of mergers and acquisitions and another executive. Although the head of M&A was actually a lawyer admitted to the Swiss bar; had previously served as the company’s general counsel; and spent much time giving legal advice to the board, his communications were not protected as would be the company’s external lawyers, the court ruled, determining that functionally, he was part of the commercial operation of the business.[xi]

This ruling is consistent with a more recent holding from the same court. In WH Holding Limited v. E20 Stadium LLP,[xii] the court held that emails between board members who were discussing a potential settlement of a civil dispute could be used against the corporation in the lawsuit.

Privilege in Germany

Few events have caused as much discussion about issues in global privilege as the raids by German authorities in 2017 on Audi as well as the on the Munich offices of Jones Day, a US law firm headquartered in Cleveland. The aftermath of those searches and seizures demonstrates that meaningfully protecting the results of an internal investigation on the basis of privilege will be unlikely in Germany, absent a change in German law.

In general, there is a German “professional privilege” of confidentiality between client and outside attorney that covers attorney-client communications. On the other hand, the position of in-house counsel is less clear. If the internal lawyer is not a member of the bar, his or her communications are not protected. Otherwise, if information is obtained for the purpose of providing legal advice (as opposed to business or strategic advice), that material should be privileged.

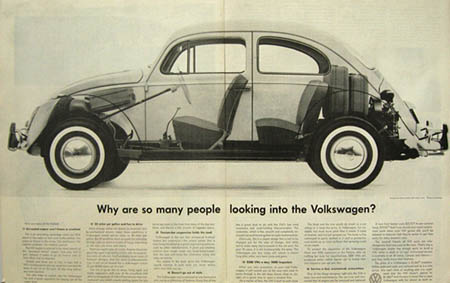

“Dieselgate”

The Jones Day case throws these general principles into question, however.

In 2015, the United States Environmental Protection Agency found that the Volkswagen Group, the German carmaker, had violated the federal Clean Air Act. Volkswagen did so, the agency said, when the company intentionally programmed its diesel engines to evade the emissions-standards required by law. (Thus, “Dieselgate”). The deception was extensive, involving millions of cars worldwide and many model-years. In the United States, Volkwagen pleaded guilty in March 2017 to criminal charges that it deceived federal and state regulatory agencies by installing the so-called “defeat devices.” As part of its plea deal, Volkswagen paid about $25 billion in fines, penalties, and restitution. Volkswagen engineers Oliver Schmidt and James Laing pleaded guilty for their roles and were sentenced to seven years and three years, respectively. In May 2018, former Volkswagen chairman Martin Winterkorn was charged with federal conspiracy and wire-fraud related to the defeat devices. Five additional defendants, including former Volswagen executives and senior managers, were indicted in January 2017. In January 2019, a federal grand jury in Michigan indicted four managers at Volkswagen luxury subsidiary Audi. Like Mr. Winterkorn, these defendants are German citizens and live in Germany. Germany does not usually extradite its citizens outside of Europe. In March 2019, the federal Securities and Exchange Commission filed a federal civil lawsuit against Volkswagen and Mr. Winterkorn alleging that they defrauded American investors. Most recently, in April 2019, German criminal prosecutors charged Mr. Winterkorn and four unidentified Volkswagen managers with aggravated fraud.

Back in March 2017, Munich prosecutors opened a fraud investigation related to the emissions-testing scandal at Volkswagen. Agents raided the headquarters of Audi, the Volkswagen subsidiary, and the Munich offices of Jones Day. Volkswagen had hired the law firm to conduct an internal investigation into emissions-testing events and also to represent Volkswagen in the United States with regard to federal investigations. As part of the internal investigation, Jones Day’s lawyers reviewed Audi actions and interviewed employees. The German agents seized documents, including the results of the internal investigation.

Volkswagen, Jones Day, and three of the company’s German lawyers litigated the privilege and constitutional questions in the German courts, but in June 2018 lost in the Federal Constitutional Court ( “Bundesverfassungsgericht” or “BVerfG”).[2]

The German Code of Criminal Procedure (Strafprozessordnung or “StPO”) provides some statutory privilege protections. stop 97 and 148 prohibit the seizure of communications between a criminal suspect and his (or its) lawyer, as well as the lawyer’s written work, and circumscribes (although does not entirely prohibit) the use of such material in court. In particular, section 97 protects documents and communications that have been entrusted to a lawyer in his or her professional capacity and remain in the lawyer’s possession. Section 148 protects correspondence between lawyer and client regarding the defense of a criminal or regulatory offense. On the other hand, a lawyer-client communication not covered by section 148 and located at the premises of the client can be seized by investigators.

The court recognized that Volkswagen’s constitutional rights were impacted by the seizure of the documents generated by the internal investigation at Audi. Although the court acknowledged that the seizure negatively impacted the attorney-client relationship, it found the seizure justified because the allegations were serious; many fraud cases were possible; and there had been guilty pleas in the United States. In other words, the government’s interest was greater than the attorney-client interest.

Also, attorney-client privilege under German law focuses on criminal defense, and Volkswagen had not been accused of any crime. The Federal Constitutional Court was concerned about possible abuse should protection from seizure be extended to every client relationship without regard to whether the client is charged with a crime or not. The court concluded that the relationship between Jones Day and Audi (as opposed to Jones Day and Volkswagen) was simply not close enough, even though Audi was eventually charged. The privilege does not apply to affiliates of the corporate client. Finally, the court found that Jones Day lacked what American lawyers would call “standing” to pursue its claims. The firm is not a German domestic legal person; its principal office is not in Germany (or elsewhere in the European Union); and the majority of its management decisions are not made in Germany (or in the EU).

Practical considerations to preserve privilege

Outside counsel. Many courts, even in the United States, are skeptical of privilege claims raised solely by, or on behalf of, in-house counsel. Whether the belief is justified or not, outside lawyers are seen as more “independent.” In addition, it is logistically easier for outside lawyers to segregate privileged material from business records; identify it as such; and maintain it in a manner that at least provides a foothold to argue that the material meets whatever privilege tests are relevant in the jurisdiction. Further, it is critical to know your jurisdiction. If you are dealing with a competition matter in the EU, for example, you may have compelling reasons to retain outside counsel under the Akzo Nobel opinion.[xiii] Thus, in addition to the usual reasons for retaining local outside counsel, privilege concerns mandate having lawyers on the ground in the relevant jurisdiction.

Retention and scope. Examine your retention agreements, to ensure they specify the client. Consider whether subsidiaries can be included, or whether they need their own, separate retention agreements with counsel. Explicitly state that the retention is not for general advice, but for legal counsel pertaining to a special engagement that includes potential criminal exposure or other government sanction. Update the retention agreement as the investigation landscape changes.

Face-to-face. Face-to-face meetings, including video meetings, are best for preserving privilege: no forwarded emails or unintended texts to worry about. Of course, it is often difficult in a global corporation to have frequent face-to-face meetings, especially across jurisdictions and time zones. If the matter is sufficiently critical for the company, however, they should be seriously considered.

Phone over email. Where face-to-face meetings are not possible, use the phone rather than email or text.

Maximize formality to maximize privilege. Contemporary business, at least in the United States, is supposedly informal and collaborative. Privilege, on the other hand, is formal and distinct. Mark and segregate privileged material; state clearly, formally, and repeatedly, that the material is privileged; and emphasize that it should be treated as such. Limit the circulation of these documents to those covered by the privilege.

Paper rather than digital agendas. If agendas are to be consulted in meetings, use paper. Print them out on paper and then, after the meeting, collect them up. Paper agendas help ensure that the substance of the meeting remains confidential — or at least more confidential than any digital agenda would be, given that digital communications are often stored, forwarded, or even posted without permission.

Put a bullet in bulleted lists. A PowerPoint presentation is already sufficiently soul-devouring. Do not compound the problem by allowing meeting attendees to carry the presentation around in briefcases that can be lost or stolen. Do not print out PowerPoint slides and do not distribute them.

They no longer make carbon paper. Ban “cc’s” (an abbreviation for “carbon copy”). Some employees seem to think that the more they “cc,” the more they communicate (or the more they shield themselves from criticism, responsibility, or second-guessing). In general, the longer the “cc” list, the more likely it is that any privilege will be lost, if indeed the email was privileged in the first place.

“Re” is a Latin artifact, not a meaningful communication. Do not re-use the same subject line in emails. Despite advances in technology, recycled “re” lines make pulling out the privileged thread more difficult and encourage thoughtless, too-rapid correspondence.

Enforce technological omerta. Look into “Silent Circle” or similar tools to minimize the permanence of emails. Use “Signal” or a similar platform for text messages. Although some criticize the use of these these apps as inherently suspect, because they delete messages or offer encryption, when used for a lawful purpose – which maintaining privilege is — they are no more sinister than a document-retention policy.

Repeat privilege incantations. Speak the language of privilege, frequently. Colleagues, officers and employees need to remember that the substance of the discussion is privileged and that the privilege is held by the company.

Conclusion

Even more than most areas of the law, privilege questions require sensitivity, wisdom, and judgment. Following common-sense prescriptions for each relevant jurisdiction will go a long way towards achieving the goals of both the business client and the law department.

[1] A control-group test limits the protection of the attorney-client privilege to those communications made by an employee who has authority to direct the company’s actions by those communications. The “control group” is usually composed of a limited number of senior employees. In Upjohn, the Supreme Court rejected the control-group test.

[2] See 2 BvR 1405/17, 2 BvR 1780/17, 2 BvR

1562/17, 2 BvR 1287/17, 2 BvR 1583/17 (June 27, 2019). See

also the court’s press release of July 6, 2018 (“Constitutional complaints

relating to the search of a law firm in connection with the ‘diesel emissions

scandal’ unsuccessful) (available at

https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2018/bvg18-057.html).

[i] Upjohn Co. v. United States, 449 U.S. 383 (1981).

[ii] Upjohn, 449 U.S. at 389 (1981).

[iii] Hunt v. Blackburn, 128 U.S. 464, 470 (1888).

[iv] Director of the Serious Fraud Office v. Eurasian Natural Resources Corp. Ltd., [2018] EWCA Civ 2006 (5 September 2018).

[v] [2003] EWCA Civ 474.

[vi] Id. [paragraph 93].

[vii] Id. [paragraph 113].

[viii] Id. [paragraph 102].

[ix] Id. [paragraph 23].

[x] Id. [paragraph 127].

[xi] See id. [paragraphs 46 and 144].

[xii] [2018] EW CA CIV 2652 (30 November 2018).

[xiii] Akzo Chemicals Ltd v. European Commission, ECJ Case C-550/07-P (September 14, 2010) (internal communications between in-house counsel and their companies’ employees are generally not privileged in European competition law disputes).

The article is reprinted with permission of the authors and the Association of Corporate Counsel as it originally appeared: Schuetz, Greg; Sharman, Jack, “Global Privilege Issues,” ACC Docket volume 37, issue 4 (June 2019): 28-35. Copyright © 2019, the Association of Corporate Counsel. All rights reserved. If you are interested in learning more about ACC, please visit www.acc.com, call 202.293.4103 x360, or email membership@acc.com.