Brand’s Memo and Dan’s Desk

Reading Time: 7 minutes.

Last month, then-Associate Attorney General Rachel Brand issued a memorandum to Department of Justice civil lawyers concerning the circumstances under which they may and may not use federal agencies’ “guidance documents” in civil lawsuits brought by the government. Ms. Brand has since left the department to take a position in the private sector, but her memorandum lives on and may have significant effect for American regulated businesses not only for civil litigation – its stated goal – but also for corporate criminal indictments and trials.

What Does The Memo Say?

The Brand Memo, which is brief, follows up on a November 16, 2017 policy memo issued by Attorney General Jeff Sessions called “Prohibition on Improper Guidance Documents.” The Brand Memo makes three points about DOJ’s civil cases:

First, “guidance documents cannot create binding requirements that do not already exist by statute or regulation.”

Second, “the department may not use its enforcement authority to effectively convert agency guidance documents into binding rules.”

Third, “department litigators may not use non-compliance with guidance documents as a basis for proving violation of applicable law in ACE [affirmative civil enforcement] cases.”

What Are Guidance Documents?

Federal agencies implement and oversee complex regulatory and enforcement regimes often produce documents that are intended – or, at least, the agencies claim are intended – to provide guidance, insight or warnings to businesses and individuals subject to regulation. Such guidance documents can be found throughout the federal government but are particularly common in heavily regulated sectors such as healthcare, pharmaceuticals, workplace safety, defense contracting, environmental protection and the like. They can have far-reaching implications in other areas: think of the discord, commentary and litigation caused by the “Dear Colleague” letter issued from the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights in the prior administration concerning its view of Title IX in the context of university disciplinary proceedings. We previously addressed Title IX and the “Dear Colleague” letter:

Guidance documents provide the agency’s interpretation of a statute or case, announce an enforcement priority or purport to impose new rules or liabilities that did not exist previously.

It is these latter uses of such documents as a substitute for notice-and-comment rulemaking or even as a substitute for an underlying statutory authorization that has subjected them to criticism by some in the business and regulated community.

What Is The Significance Of The Memo?

Although the Brand Memo was criticized in the media by persons who feared that it would weaken federal oversight in critical areas involving human health, safety, the environment and financial regulation, it seems to restate what should be a modest point: that federal agencies, in the absence of complying with the statutory requirements for making new regulations and rules, cannot simply do so by drafting a memorandum to that effect. Further, DOJ cannot do indirectly by litigation what the agencies cannot do directly by memo-publication.

On balance, the Brand Memo seems to be a reasonable tap on the brakes of a process that has sometimes been misused by federal agencies, even with good intentions.

What’s The Catch?

In the past, in civil cases, DOJ lawyers have claimed that the fact that a business or person has not complied with an agency guidance document was proof that the business or person violated the law. If a healthcare provider acted inconsistently with the guidance documents issued by the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services, for example, the government might then argue that the provider’s violation of the guidance document anti-kickback examples was proof that he or she violated the Anti-Kickback Statute.

Under the Brand Memo, DOJ lawyers “may not use noncompliance with guidance documents as a basis for proving violations of applicable law in [civil] cases.”

Notably, however, the Brand Memo goes on to say that DOJ “may use evidence that a party read such a guidance document to help prove that the party had the requisite knowledge of the mandate.”

And therein lay the rub.

The government wants to prove, of course, that a civil defendant “had the requisite knowledge of the [statutory or regulatory] mandate” so as to fend off a defense of confusion or mistake. In civil cases, however, the burden of proof is “preponderance of the evidence” or “more likely than not.“ Compared to the criminal standard of “proof beyond a reasonable doubt,” the civil standard as to the knowledge of a sophisticated business person or corporation is often readily met. The outcome of the civil case will often turn on other factors: Is this the right statute, rule or regulation? Is the regulation valid? Is there an exception in play? Is there an intervening cause? Was there actually loss or damage? Is there a valid counterclaim or offset?

In a white-collar prosecution of a business or individual in a heavily regulated sector of the economy, proving “requisite knowledge of the mandate“ is sometimes difficult but always critical for the government’s case. In many white-collar cases, most events and facts are not disputed. Unless documents have been fabricated, a check or wire transfer is usually what the record shows it to be. A contract observes all the formalities of a contract, and the parties may operate under its terms. The minutes of a city council meeting may accurately reflect what happened at the meeting.

The government must prove some level of “corrupt intent,” or at least that the conduct was “willful” and that the defendant knew it to be generally wrong. At what point does the political contribution become a bribe? Is the contract a legitimate business arrangement? Is the check actually a commission payment or is it a kickback?

Dan’s Desk and The Magic Jumping Pen

To explore the last question –a commission payment or kickback – let’s consider the case of Dan’s desk and the magic jumping pen.

Dan (not his real name) owned a specialty pharmacy. He was indicted. Allegedly, he violated the federal Anti-Kickback Statute by disguising payments for referrals for covered services as commission payments to the referring party. He went to trial. At trial, the government needed to prove, among other things, Dan’s wrongful intent.

Dan and his company had reputable lawyers and law firms who advised them on their business dealings and drafted their contracts, including the contract with the alleged referral source. Although his company was not public, it had a reputable outside auditor. The company had also been subject to random file-audits by the appropriate regulatory authorities.

Dan was a successful pharmacist, not a lawyer. How was the government to put on evidence of his wrongful intent? If the government could prove that Dan knew what the Anti-Kickback Statute said he could and could not do, that might go a long way towards proving intent.

But how? By making sure the jury saw the papers on his desk – aided by a pen that jumped on its own.

Government agents had executed a search warrant on Dan’s business, and they took photographs. A lot of photographs.

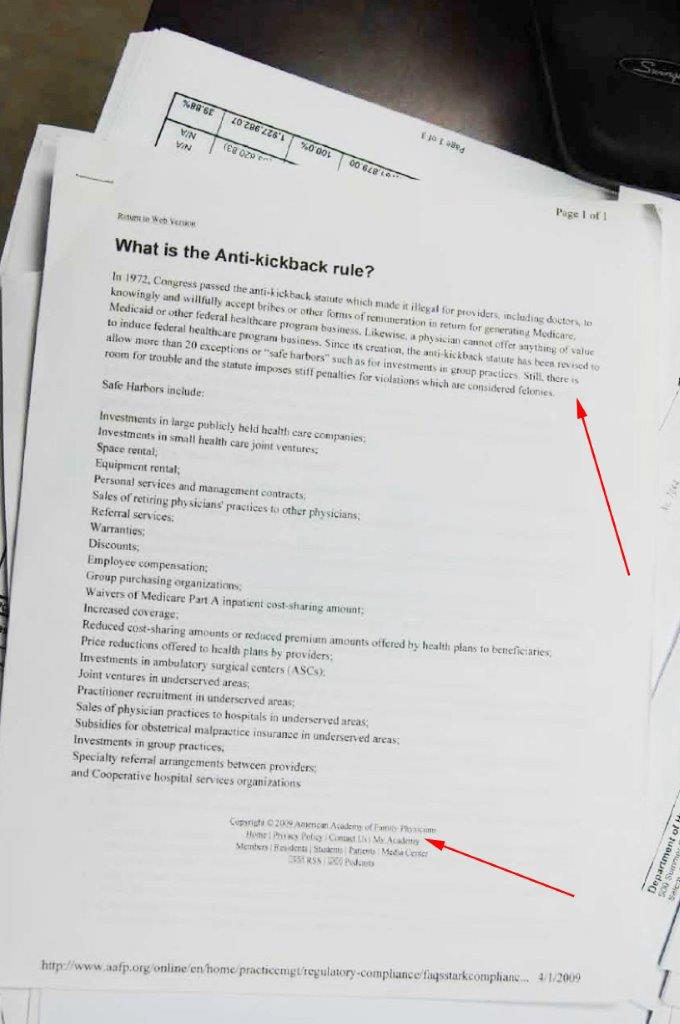

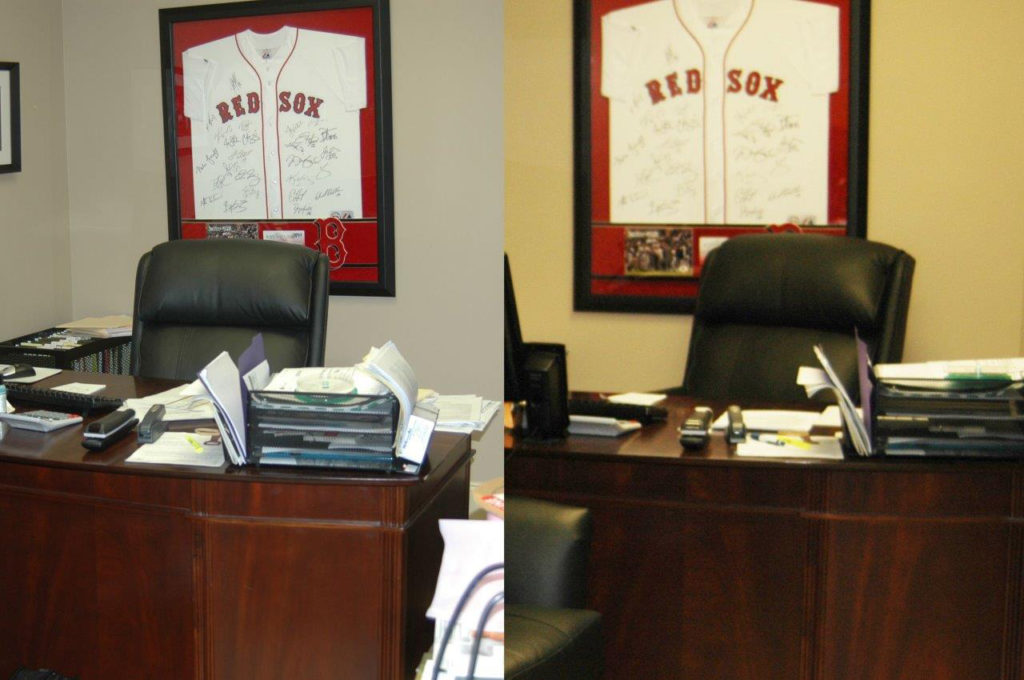

They took a photograph of a document that they said was front and center on Dan’s desk:

It contained a detailed discussion of the Anti-Kickback Statute.

Clearly, Dan had more than enough knowledge of the requisite mandate under the federal anti-kickback statute.

Or did he?

When we looked more closely at all of the photographs provided by the government, we noticed something odd.

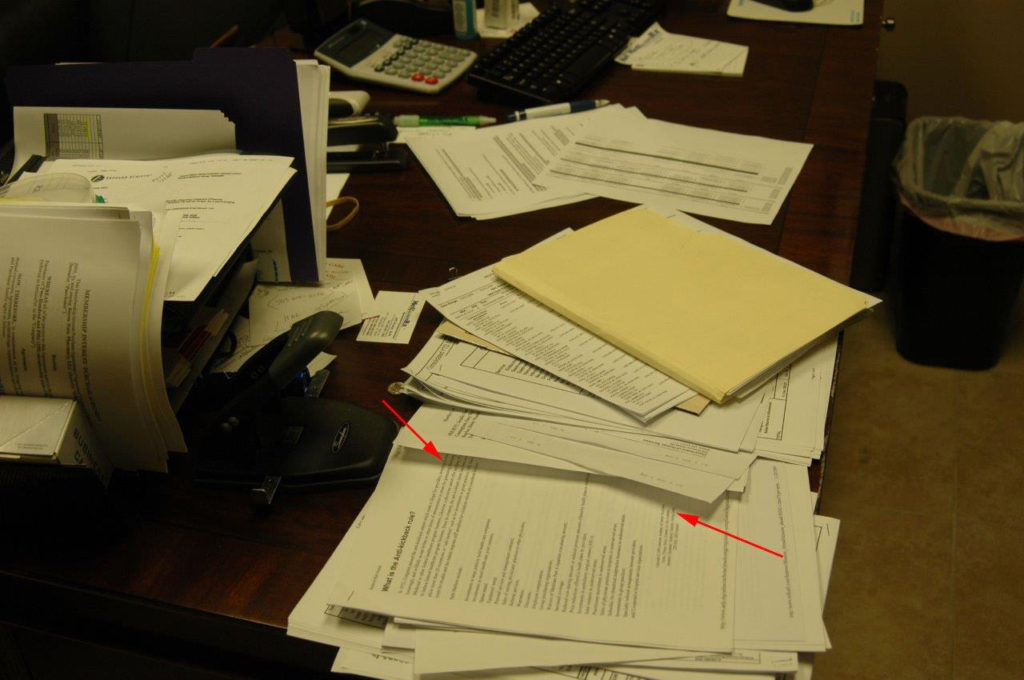

Here is another photo of the writing surface of Dan’s desk:

Notice where the Anti-Kickback Statute document is. And, notice what documents are at the center of the desk:

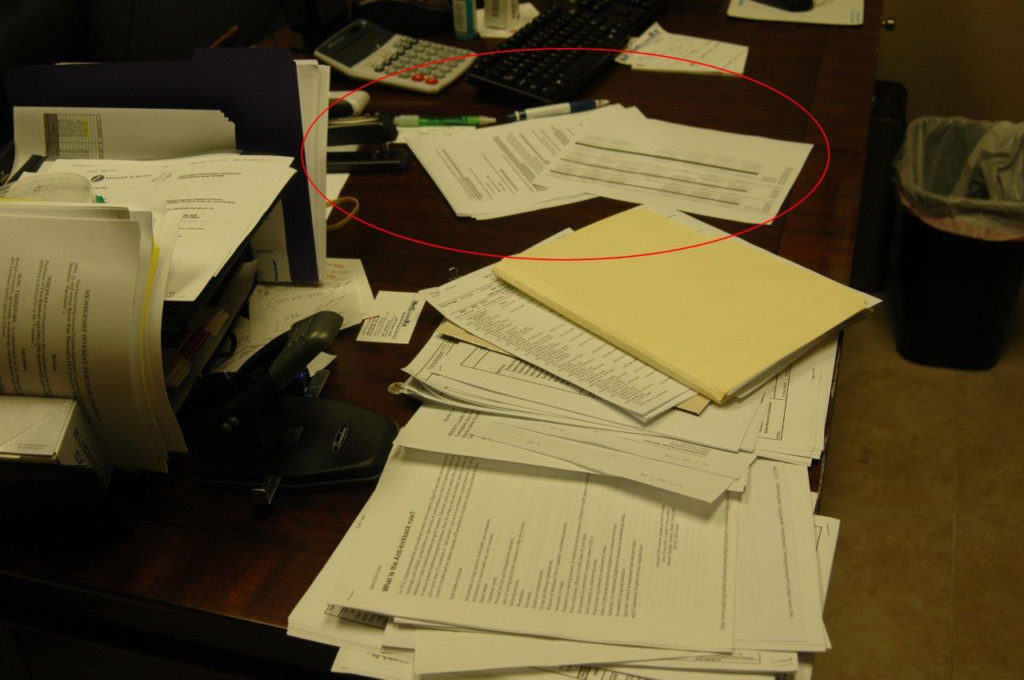

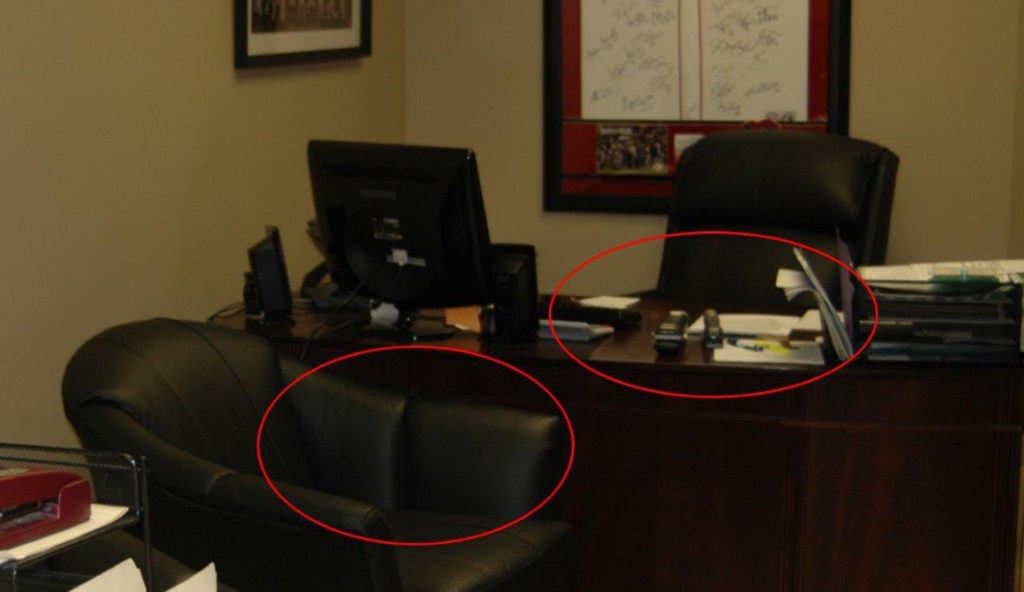

Here is a photo looking into the office:

And a photo looking into the office after the agents had entered:

In the two photos above, notice the accordion folder in the chair and the arrangement of the stapler and pens on the desk.

Here is a follow-up side-by-side photo from the same vantage point:

Notice anything?

Exactly.

In the photo on the left, the Anti-Kickback Statute printed-out document is just one of many papers, and only partially visible. There is no pen between the stapler and the highlighter.

In the photo on the right, the AKS document is placed squarely before the executive chair. There is now a pen between the stapler and the highlighter.

What happened?

The agents, having gone through the desk and noticed a document about the Anti-Kickback Statute, had staged the desk so that the any anti-kickback information was front, center and clear. In the course of tidying things up, though, the agents have failed to put the pan back where it had been.

On the witness stand, under cross-examination, the agent admitted as much, claiming that the staging was just for clarification purposes. In the courtroom, by toggling on-screen between the photographs, we could make the pen “jump” for the jury back-and-forth over the highlighter.

The moral of the story? A guidance document can be an important factor – perhaps the critical factor – in whether a white-collar defendant is convicted or acquitted. Despite disclaimers that the Brand Memo governs only civil cases and that it does not prohibit use of a guidance document to establish “requisite intent,“ look for defense counsel to identify opportune moments to use the the memo to exclude evidence at trial or even to dismiss indictments.