Jerry Jeff Walker, Agonistes

Reading Time: 5 minutes.

Jerry Jeff Walker died last month. One gets the outline of his career from obituaries in the New York Times, in The Guardian and on NPR. Walker’s only truly popular release, of course, was “Mr. Bojangles.” From the Times:

A waltzing ballad about an old street dancer Mr. Walker had met in a New Orleans drunk tank, “Mr. Bojangles” was first recorded by Mr. Walker for the Atco label in 1968. The song achieved its greatest success in a folk-rock version that reached the pop Top 10 in 1971 with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and went on to be covered by a wide range of artists, among them Nina Simone, Neil Diamond and even Bob Dylan. Sammy Davis Jr. included it in his stage show and performed it on television.

Walker maintained a cult following until his death but he never hit the big time. He was too strange, his voice too rough, his life — on stage and off — too drunk until later in life. Walker is for me, however, one of those signposts that one comes across several times in life, perhaps first in late childhood or early adolescence. These signposts point one way or another and are critical to one’s revealed and developed character as an adult because, before coming up on the signpost, you did not know the signpost would be there. Perhaps you did not even have a map.

My father died suddenly in early 1973, when I was twelve years old. (More on that here). Later that year or the next, my tennis coach took me to a Jerry Jeff Walker concert at Foster Auditorium, down the street on the campus of the University of Alabama. In American history, Foster Auditorium will be remembered as the site of Governor George Wallace’s infamous “Stand In The Schoolhouse Door” on 11 June 1963. For me, it had an additional, personal significance.

By 1973, Wallace was in a wheelchair, the victim of an assassination attempt on the campaign trail. Competitive tennis was taking over my life. My coach, a circuit-playing pro named Jim Ward, was a figure of mystery and adulation. He had long shaggy hair, drove barefoot — something neither of my parents would ever have considered doing— and the gas pedal in his car was fashioned in the shape of a bare foot.

More strikingly, my father had been a fan of Volkswagen Beetles. After my father’s death, my mother sold his Beetle to a friend at a dealership. By chance, fate, or providence, Jim Ward had bought the vehicle, a nice green Beetle that reminded me of my father. It troubled my mother when Jim would drive up into our long driveway in my father’s car, a poignant memory of how he had puttered up that driveway and would do so no more.

But for me, the Beetle meant even more mystery and connectivity, and I got plenty of that at the Jerry Jeff Walker concert.

I had attended only one concert before, an event by The Fifth Dimension to which my mother took me. The Fifth Dimension is best known, of course, for “Age of Aquarius“:

Although energetic and vaguely hippie-ish there at near-ground-zero of Watergate, the Fifth Dimension was clean, uplifting, and organized. It was to New Age pop as Star Trek was to residual JFK New Frontierism. If Apple had been a powerhouse in 1974, The Fifth Dimension would have provided one of its soundtracks.

Jerry Jeff Walker was none of these things. Foster Auditorium was old but had excellent acoustics and hosted a wide variety of luminaries in its day including the Grateful Dead and Neal Young. My tennis coach had gotten seats in the third row, a location that felt to me as though I were on stage. The Lost Gonzo Band warmed up and waited for Walker, who eventually stumbled out onstage.

Even with my dewy eyes, I could tell Walker was wasted. After a fellow band member helped him strap on the guitar, he stepped up to the microphone and said: “Good evening….” He paused, turned, and asked a band member the name of the city in which it was evening. Walker then managed “Good Evening, Tuscaloosa,” the vowels rolling around in his mouth like bourbon ice slush in the bottom of your cup at a football game.

Although I had been told that both Dean Martin and Jackie Gleason spiked their on-air coffee cups with whiskey, I had always assumed that artistic performance under the influence was not possible. I was about to turn to my tennis coach and ask, over the din, how this was possible when Jerry Jeff Walker and the Lost Gonzo Band started into Guy Clark’s “LA Freeway.” The music was arresting, unvarnished, and actual in a way I had never experienced. If the Fifth Dimension were Apple and Star Trek, this was something different – untidy, bloodlined, limned with self-destruction and dusty with longing.

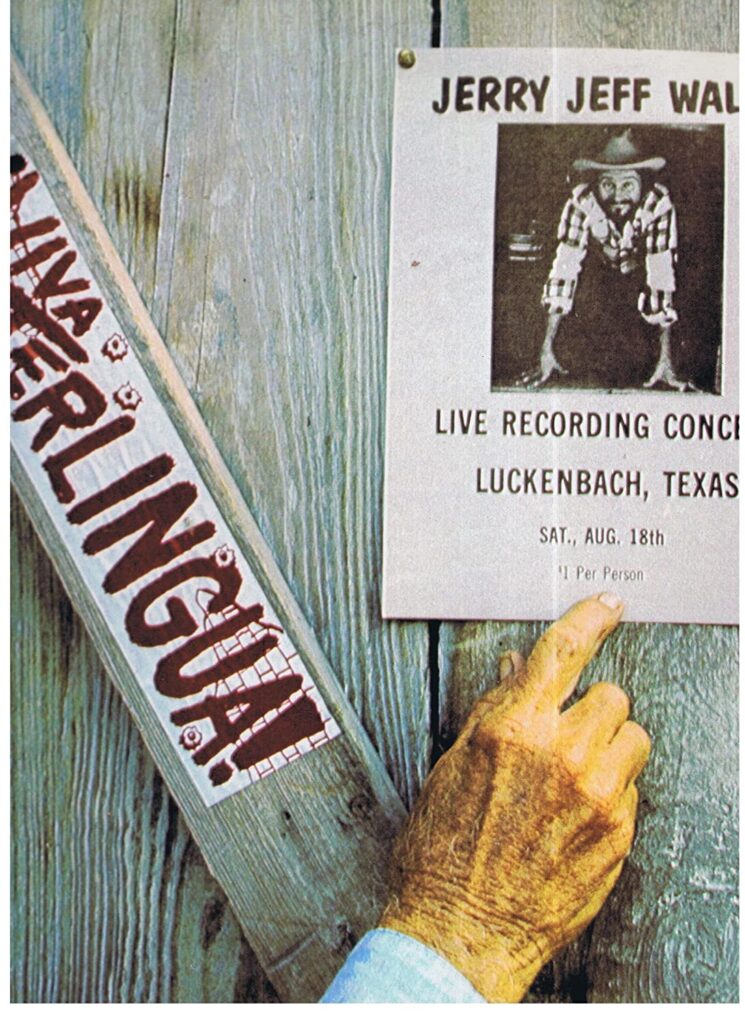

I bought Viva Terlingua as soon as it came out and listened over and over to its wonderful collection of songs including “Gettin’ By,” “Desperadoes Waiting for a Train, “Sangria Wine,” “Little Bird,” and, of course, “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother.”

Listening to Jerry Jeff Walker today, I take pleasure in the work but, although he sings — a lot — about old men, his music may be primarily a young man’s music in the way that novelist Thomas Wolfe (You Can’t Go Home Again) or Welsh poet Dylan Thomas are better consumed when one is young. Still, Jerry Jeff Walker in an old basketball auditorium in the early 1970s, a place where George Wallace tried to prevent a young woman from registering for college, opened up an archaeology for me. The music offered a way of looking at the past and at the future that I had never considered, something betokening the differences between the world of a boy and the world of a man.

So . . . Viva Terlingua.

Here is a 1970s clip of “Up Against The Wall”: